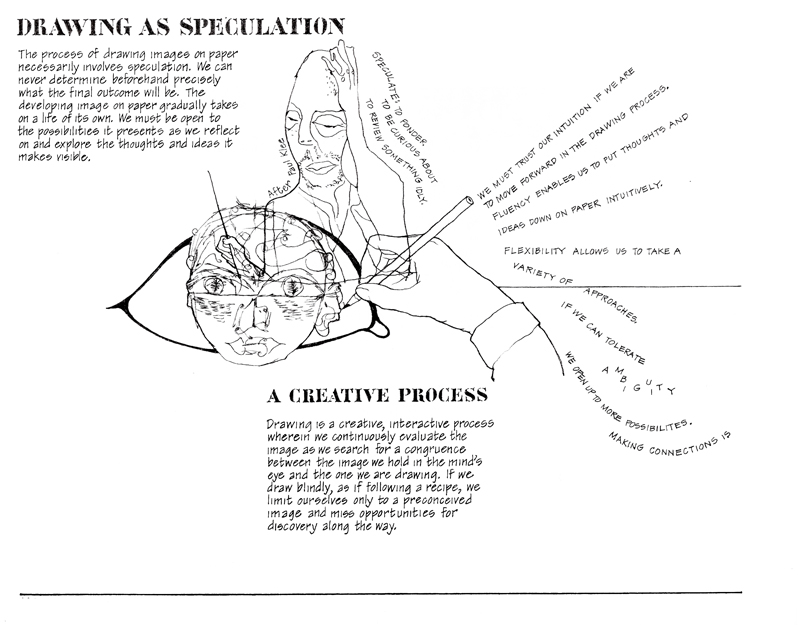

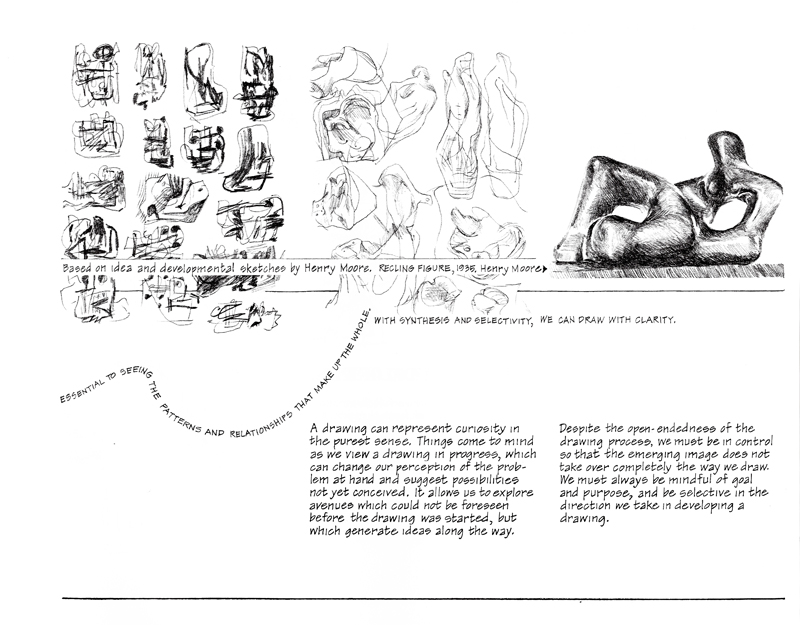

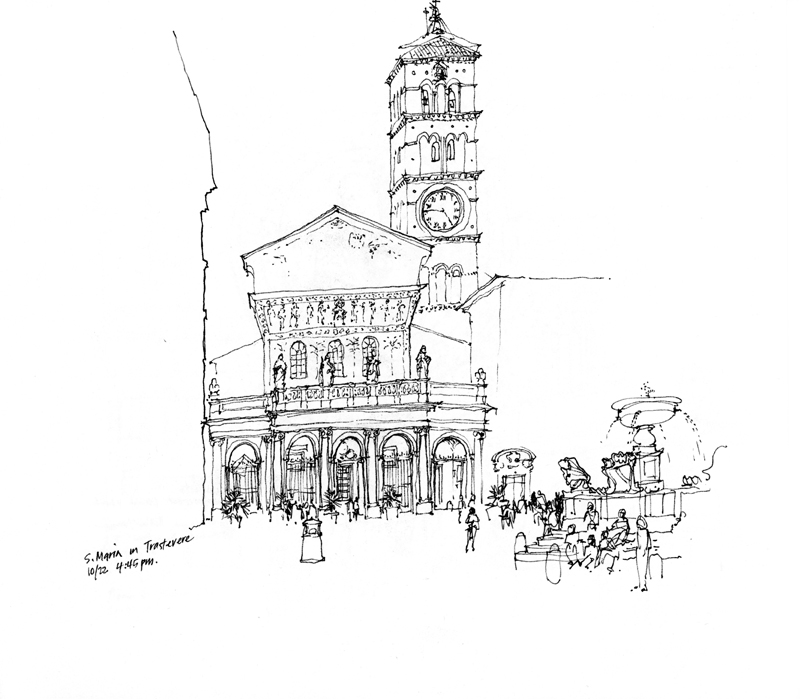

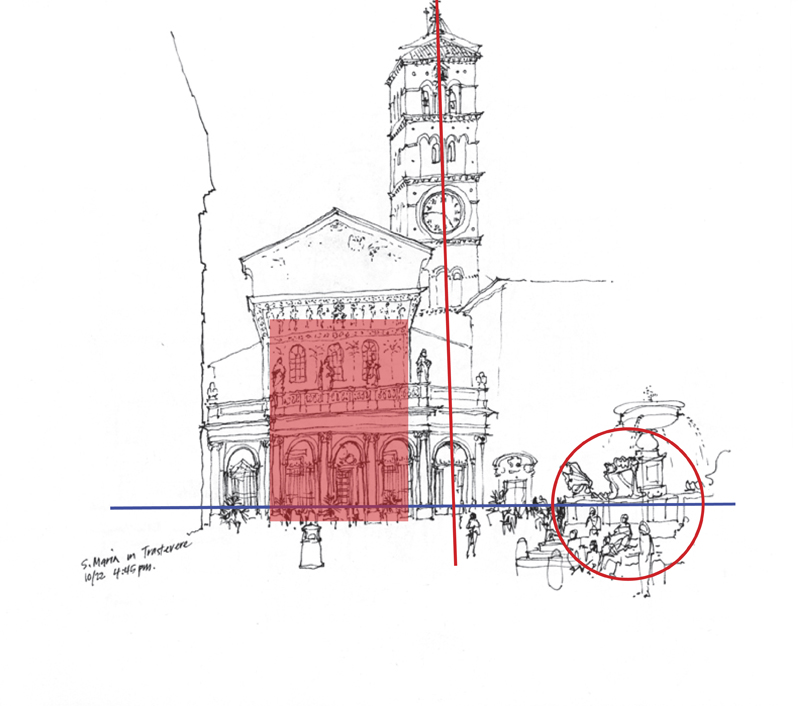

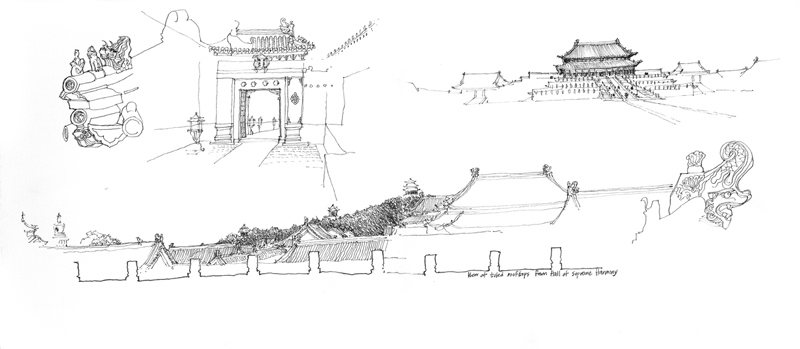

Whenever we do a drawing or sketch, we typically intend to do our very best, even if the results do not always match our expectations. Like a conversation, the drawing process can sometimes lead in a direction we could not foresee when we started. As it evolves on paper, a sketch can take on a life of its own and we should be open to the possibilities the emerging image suggests. This is part of the thrill of drawing—to work with the image on a journey of discovery.

So a strange thought came to mind—is it possible, in a conscious, deliberate manner, to do a “bad” drawing? Have you ever considered doing a “bad” drawing from the outset? I personally think this would be a very difficult thing to do.