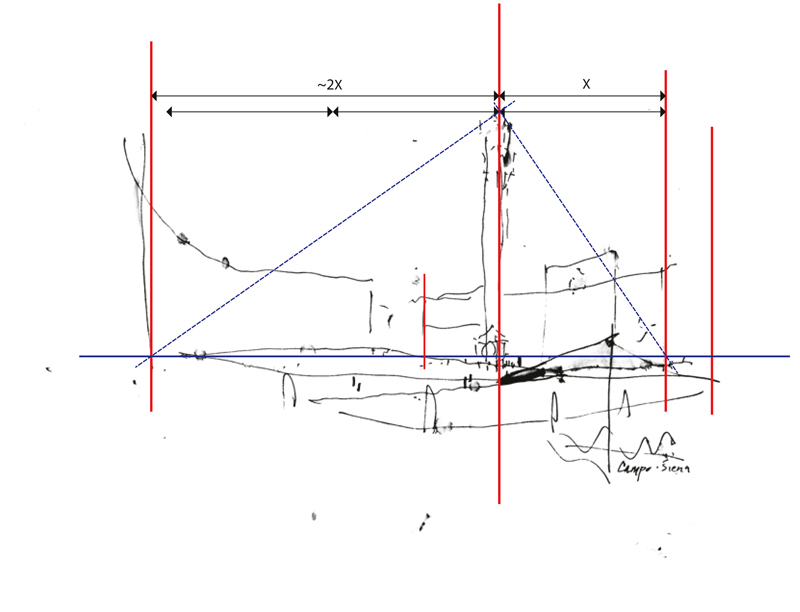

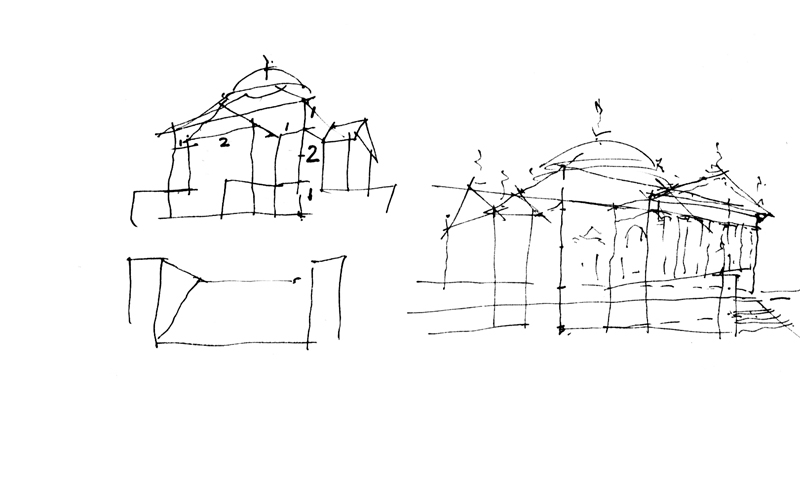

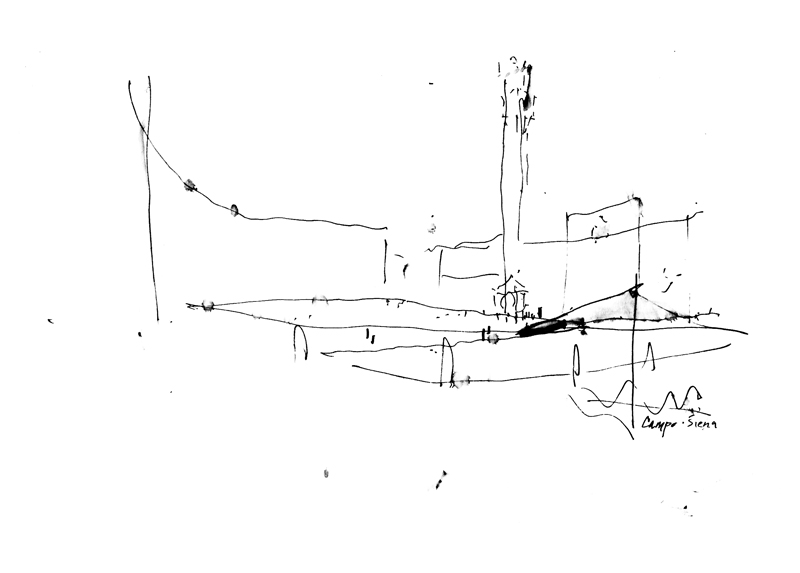

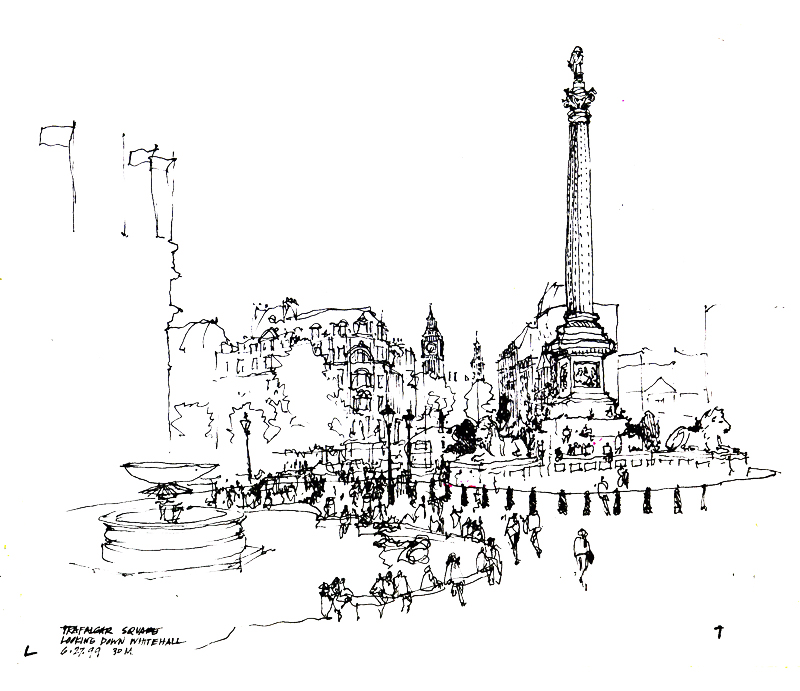

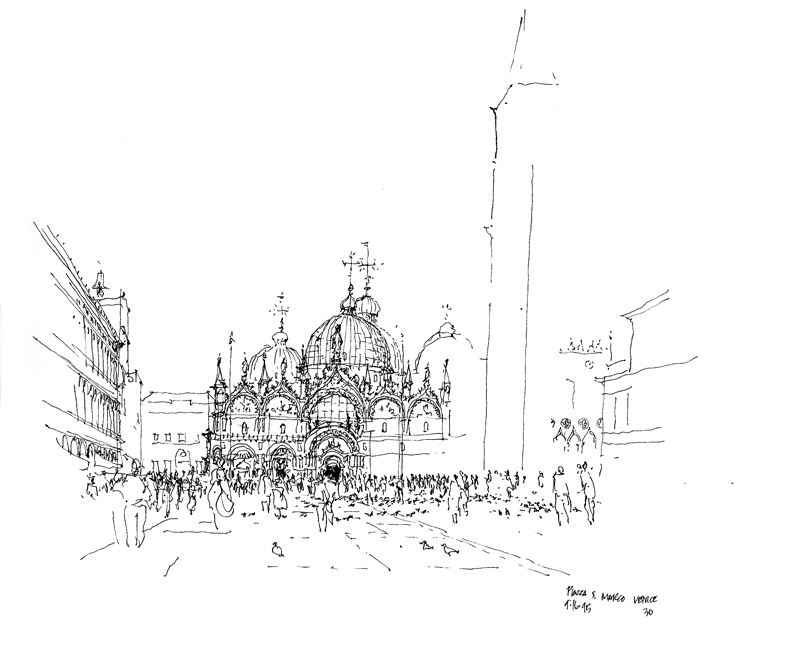

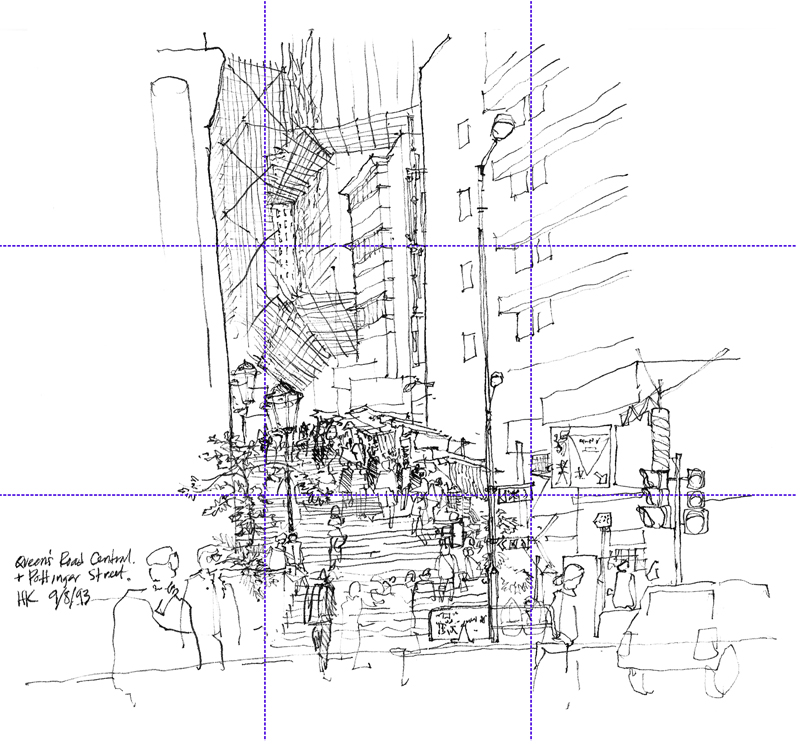

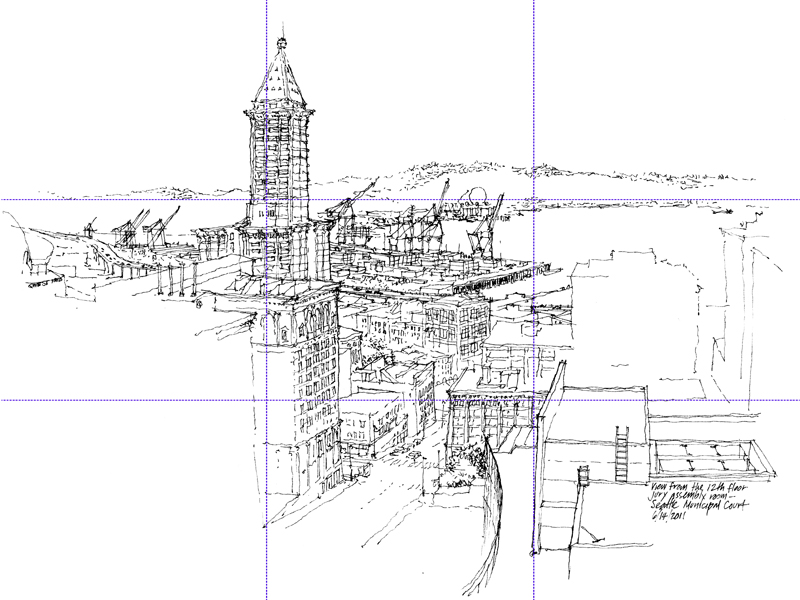

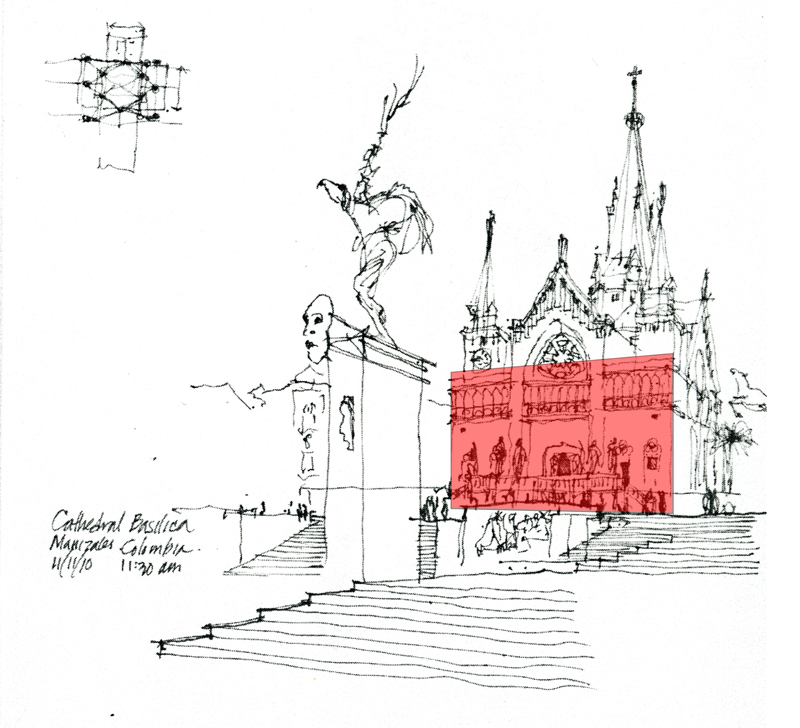

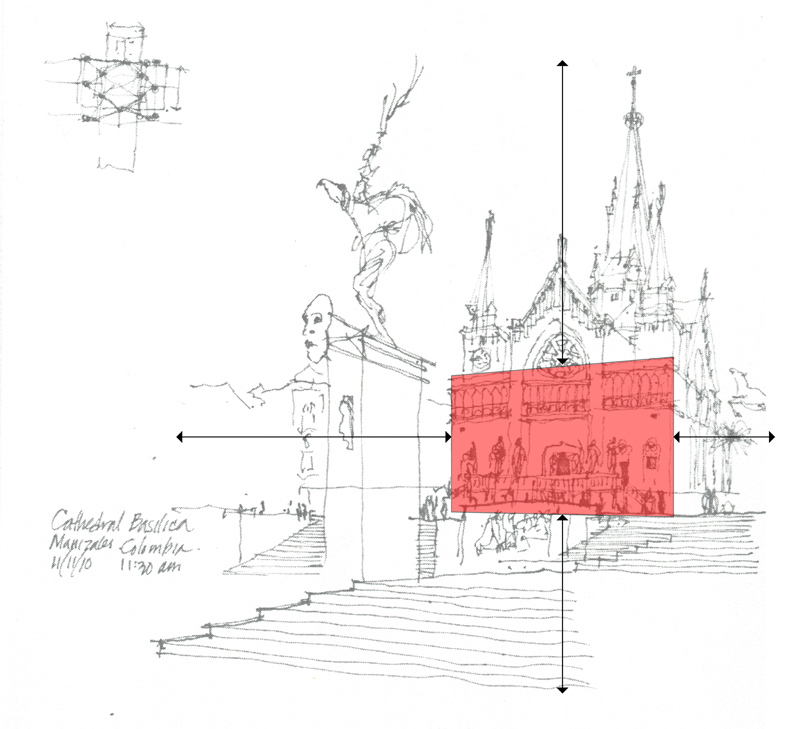

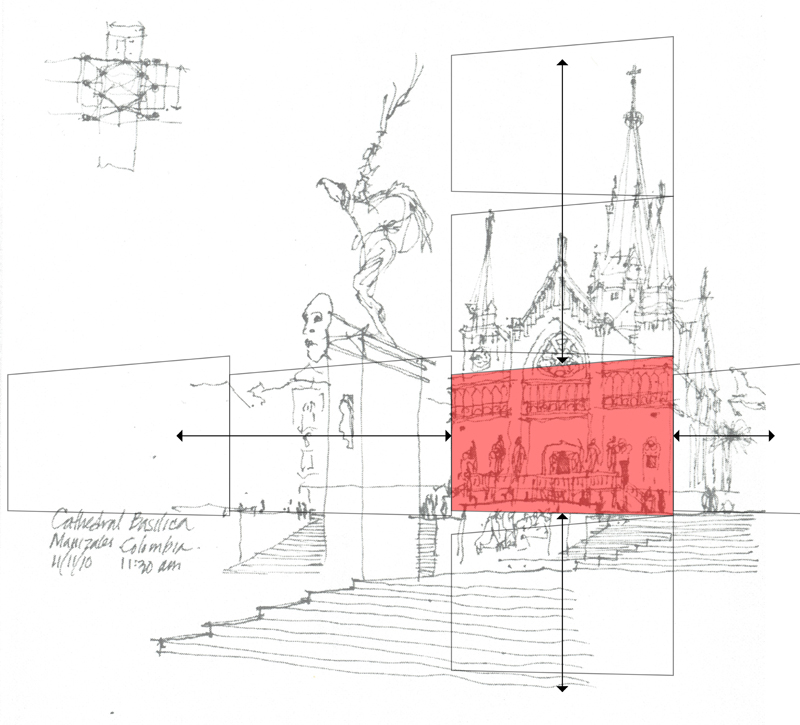

Using the same broad outline of the Campo in Siena from two posts ago, I’ve overlaid the sketch with a diagram of the important points that I visualized in the scene—the extent of my view, the relative position of the Torre del Mangia, and the foreshortening of the Palazzo Pubblico.

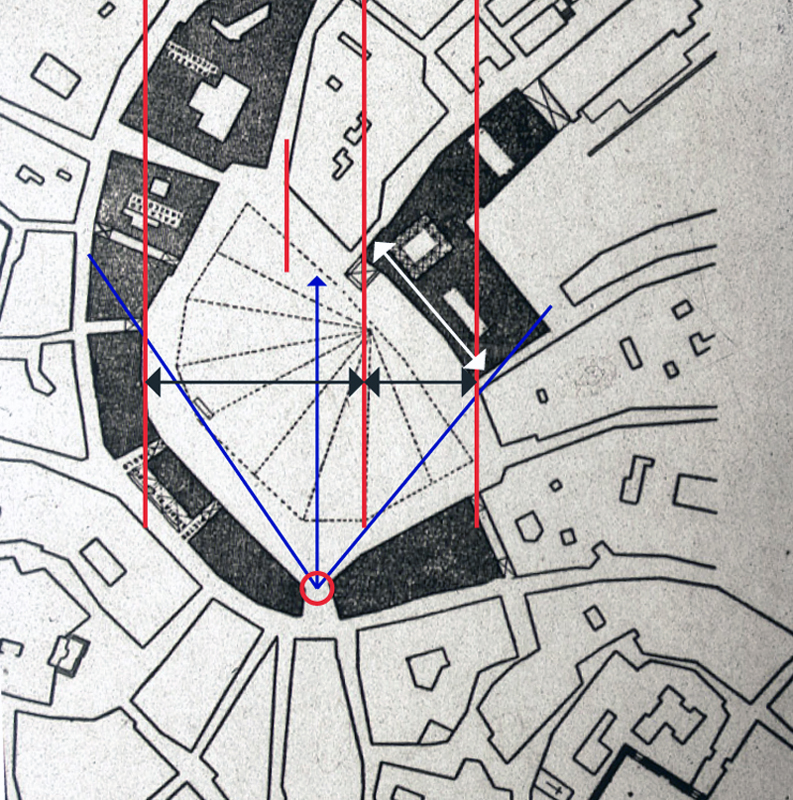

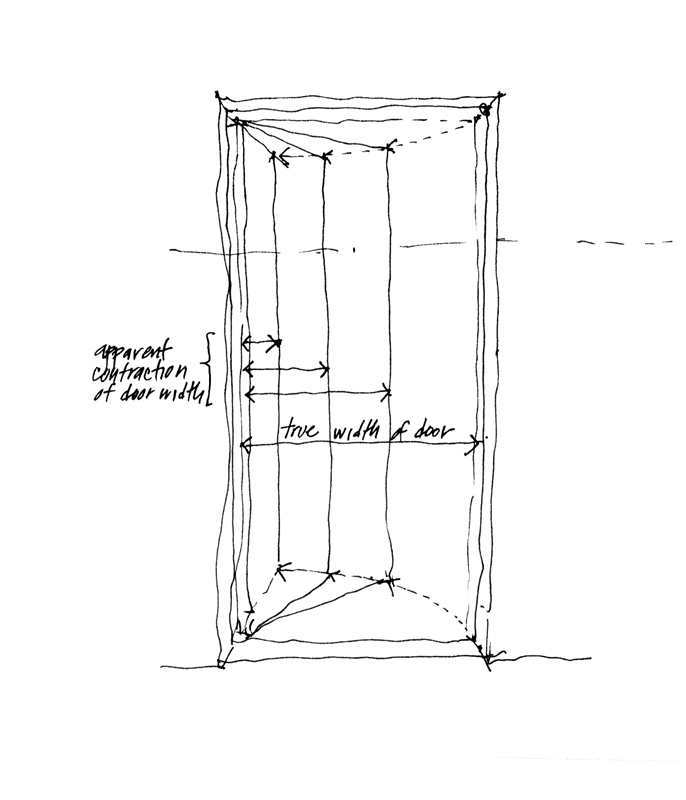

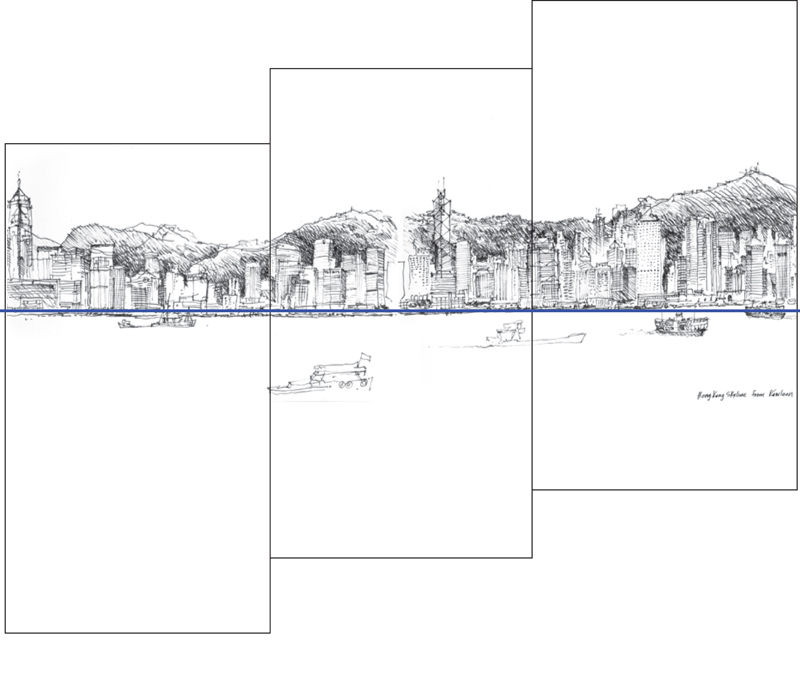

To further illustrate the phenomenon of foreshortening, I’m using a plan diagram of the Campo to show where I stood as I sketched and my angle of view. You can compare the actual width of the Palazzo Pubblico, shown with the white arrow, with my foreshortened view of it, shown with the black arrow, and notice its position relative to the horizontal sweep of the Campo space.

You can also see, both in plan and in the perspective sketch, the positioning of the Torre about one-third of the way across from the right-hand edge of the view. I visualized diagonals to estimate the height of the Torre relative to the width of the space.

While these are necessarily optical judgments, not precise measurements, seeing these types of relationships and imagining them on the page as you set up a drawing on location are important steps in the process.