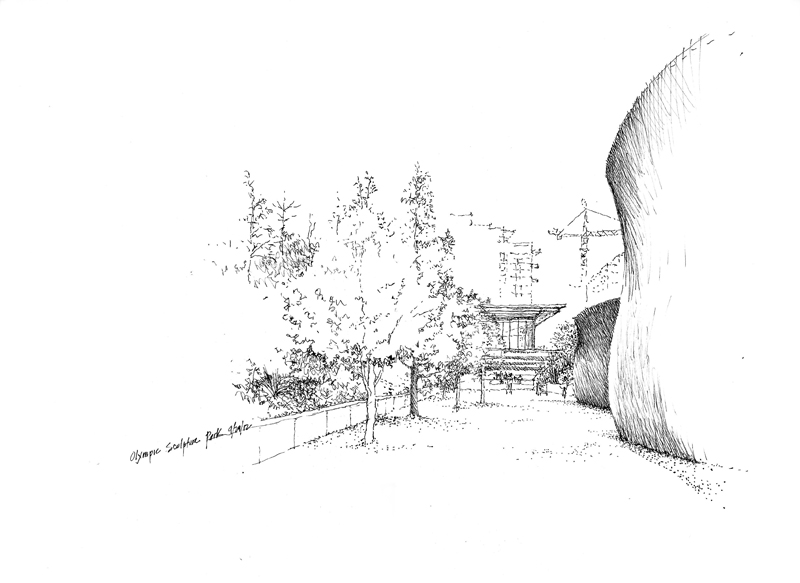

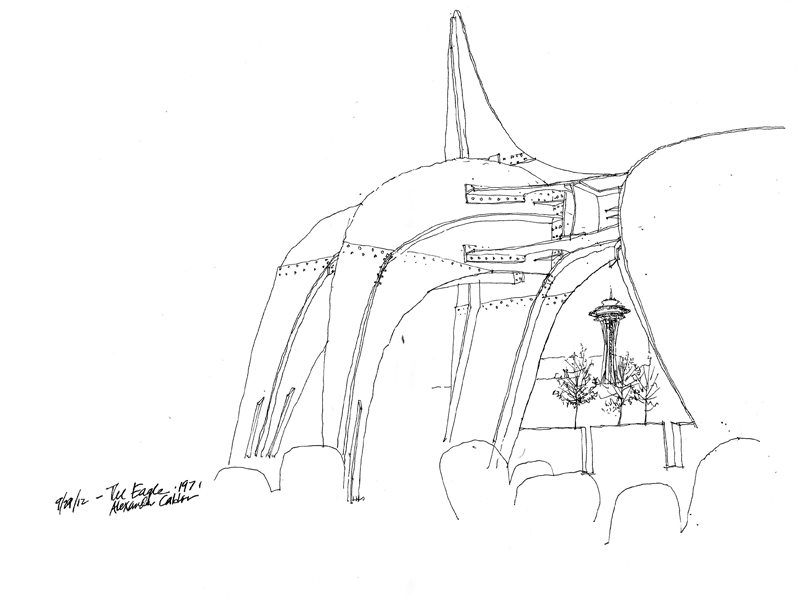

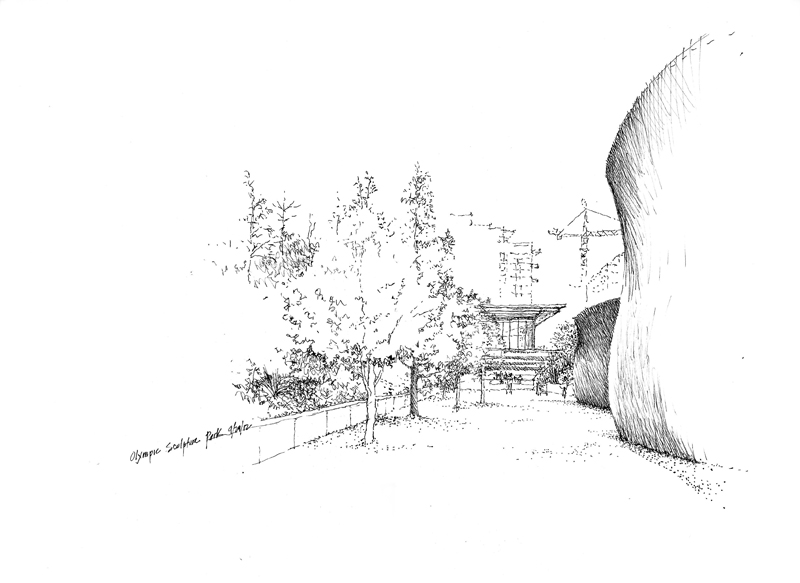

A few Seattle UrbanSketchers joined Washington State University students and their professors Bob, Kathleen, and Linda in a sketching session yesterday at the Olympic Sculpture Park. Here are a couple of my drawings to continue my previous post about drawing on location.

A photograph, whether viewed in print or on a computer screen, is a static, two-dimensional image that makes it easier to see shapes, patterns, and relationships. For some, this is an advantage. But it can be a hindrance if the flatness of the photograph prevents us from interpreting, composing, and editing more freely the visual and spatial relationships before us. When drawing on location, we are not required to recreate or reproduce exactly the visual information that a camera might capture. We can squint or “look askance” to see light-dark patterns better; we can shift our gaze slightly to block out visual noise or improve the drawing composition; we can deliberately underplay some of the visual information to emphasize others.

For example, the sloping ground and trees on the left and part of Wake, the large steel sculptures by Richard Serra in the foreground to the right, frame the PACCAR Pavilion beyond. So as not to lose the pavilion, I only suggested the apartment buildings in the background. This editing was easier to do on-site than if I were drawing from a photograph.

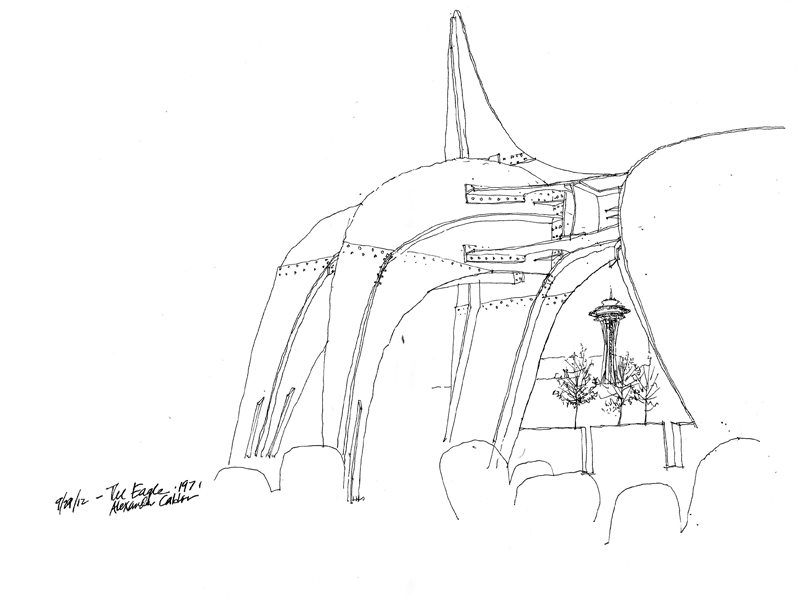

As I mentioned in the previous post, the drawing process often leads to unexpected results. I selected the spot to draw Alexander Calder’s The Eagle so that it framed the Space Needle in the distance. My intention was to draw the entire sculpture but soon after I started, I realized the image wouldn’t fit if I were to maintain reasonable proportions. So I proceeded to draw as much detail as I could and omitted the rest so that I would not lose the sculpture as a framing device.

“Art does not reproduce the visible; it renders visible.” Paul Klee