In thinking about how to teach drawing more effectively and how others might better learn how to draw, I find that books are a useful companion to which one can refer early and often. There is something comforting about seeing and feeling physical drawings on a page. When a book is well written and illustrated, one can almost hear the voice of the author. But the thing that books lack is the guiding eyes and hand of a live instructor when looking out upon a scene and trying to understand how to capture whatever it is that interests us. For this, one must take classes that deliver hands-on instruction.

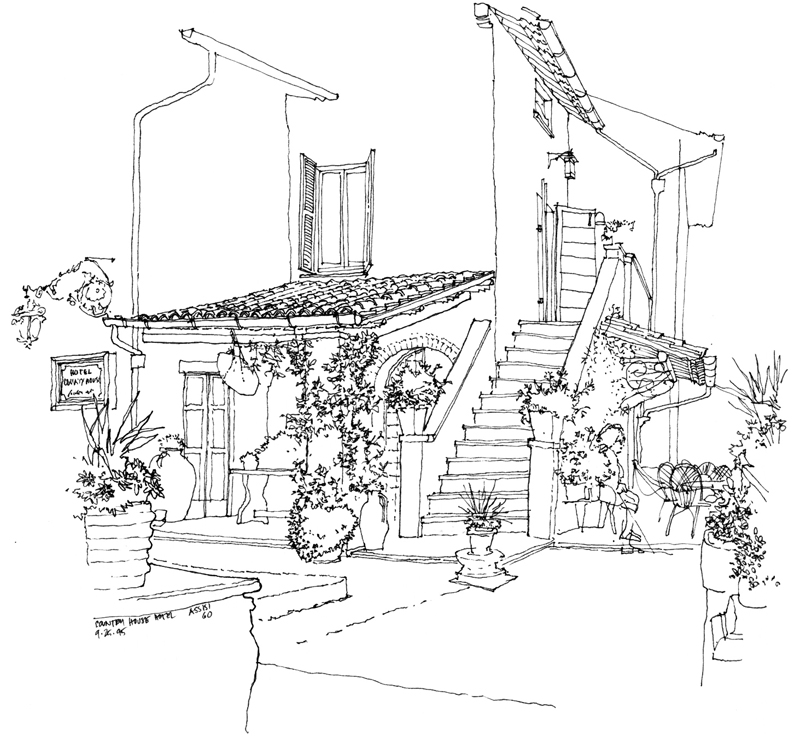

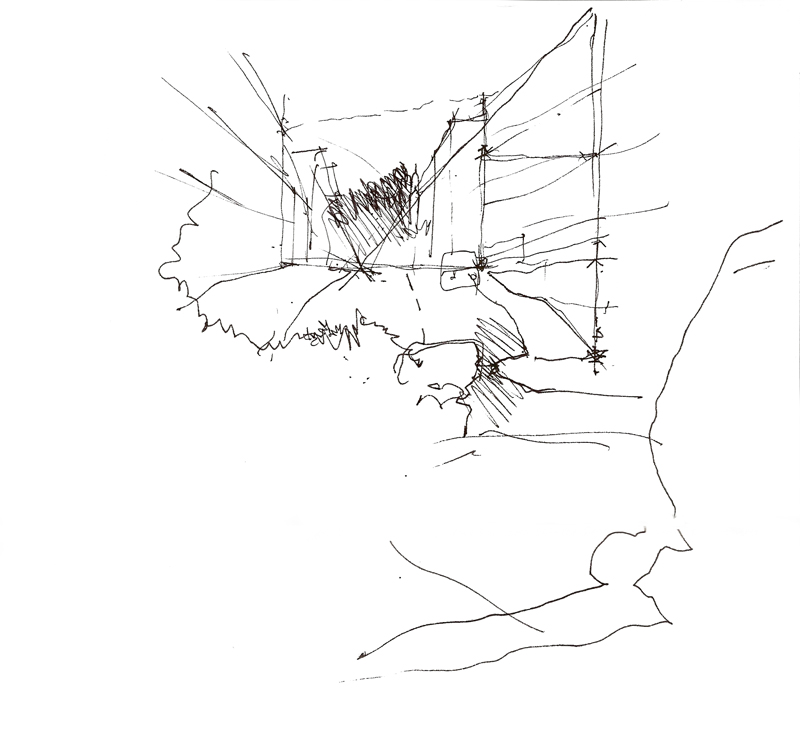

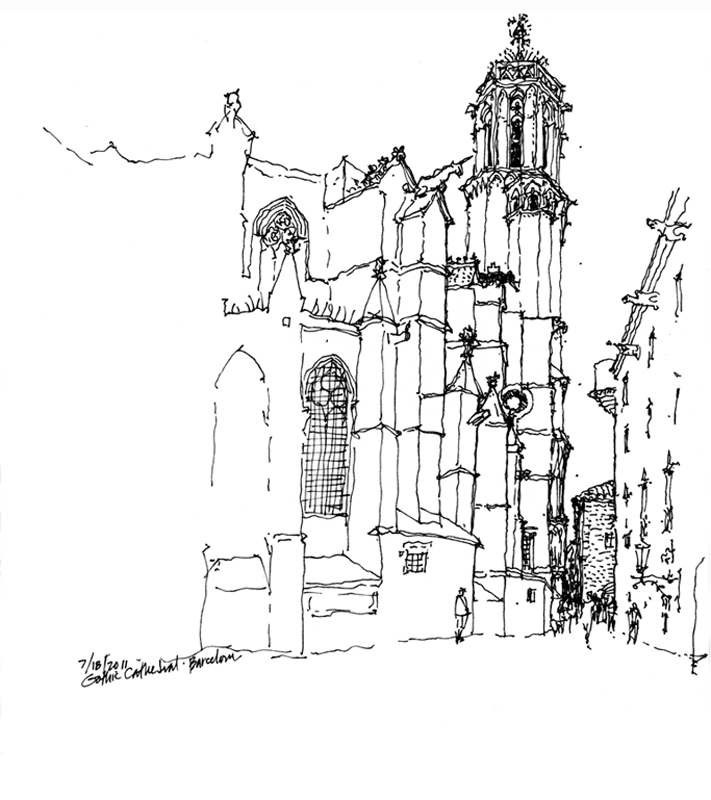

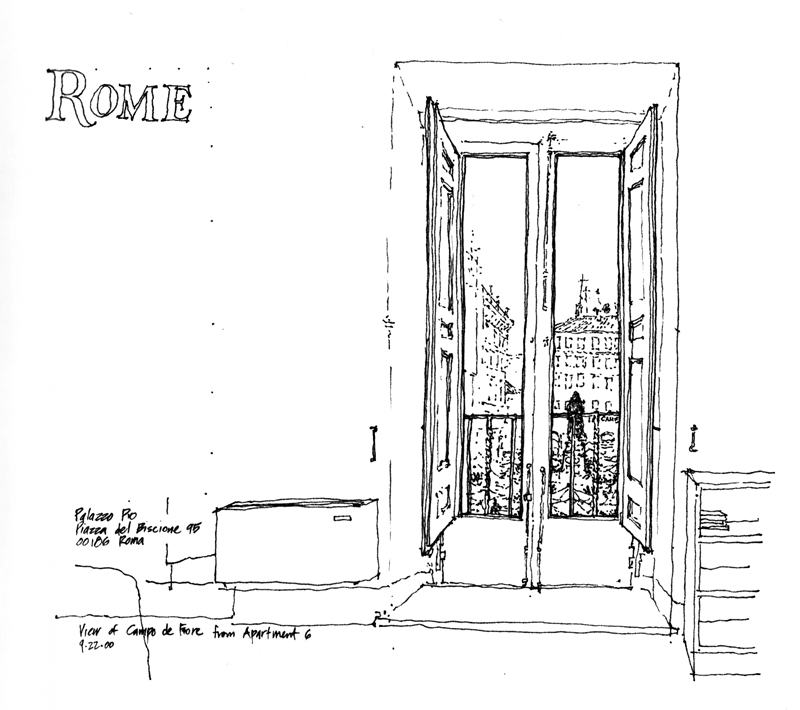

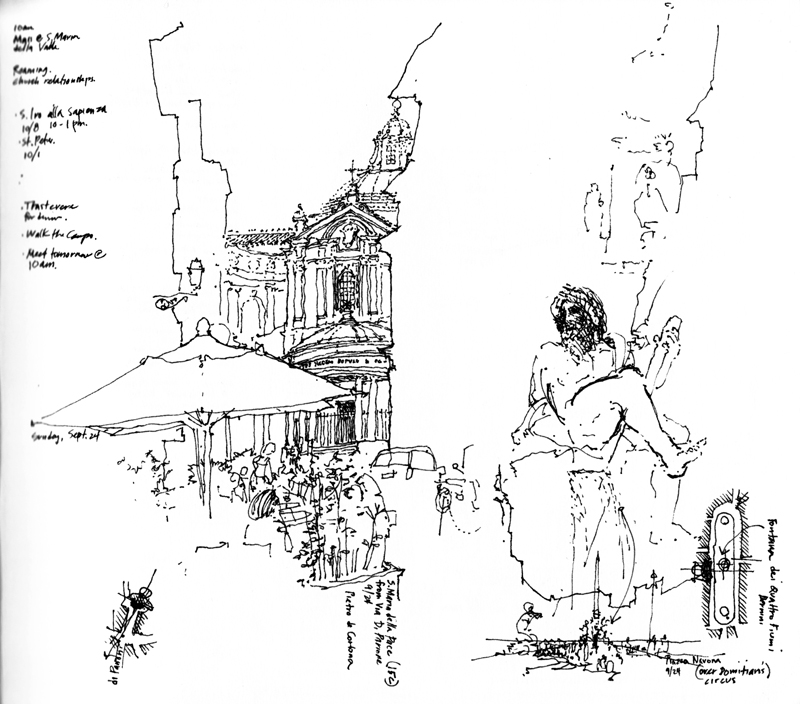

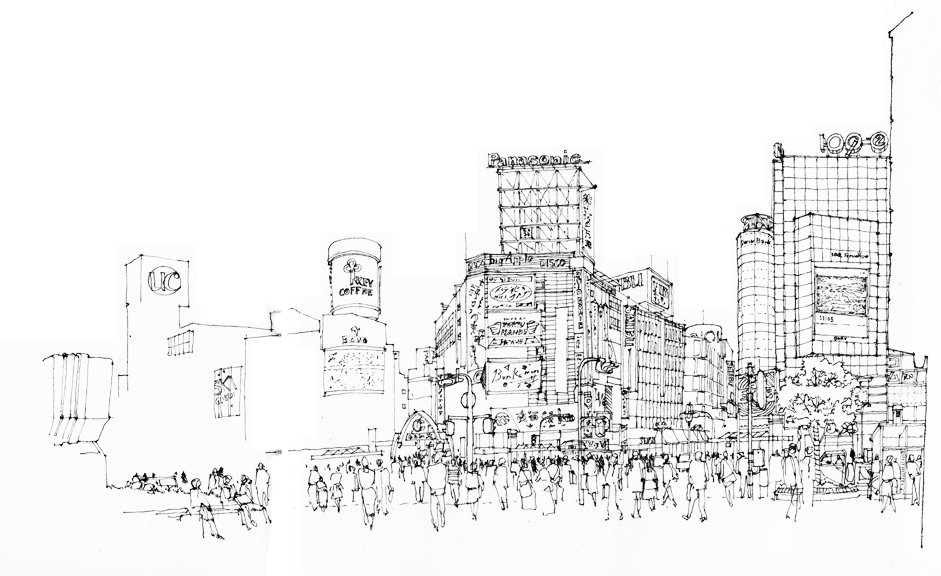

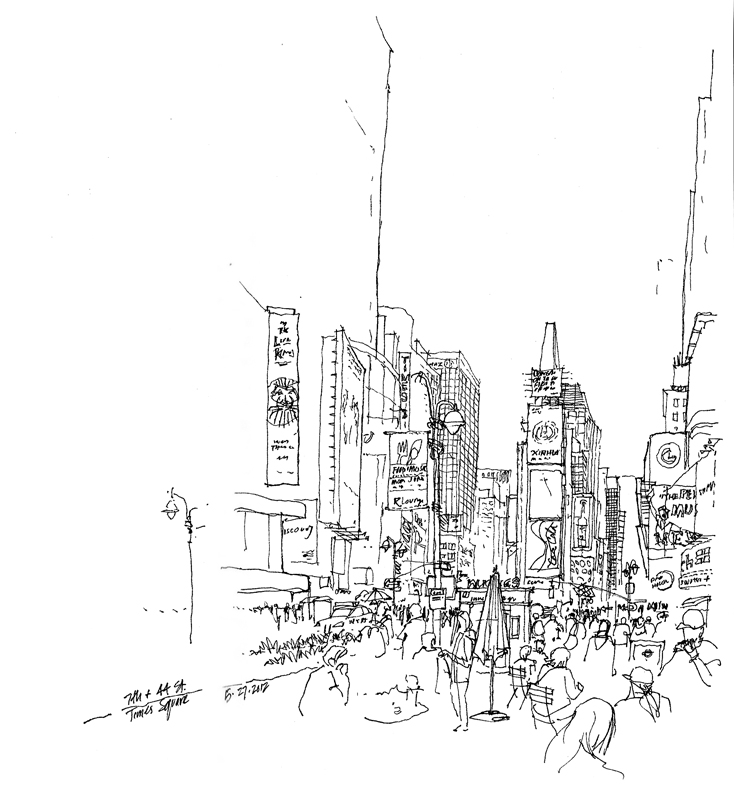

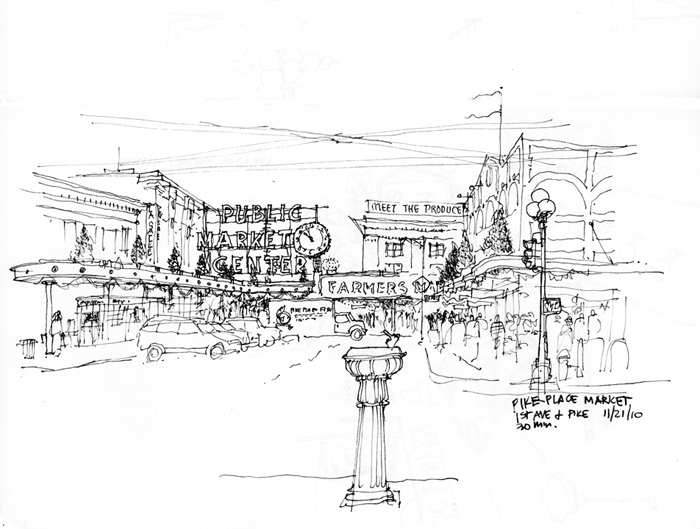

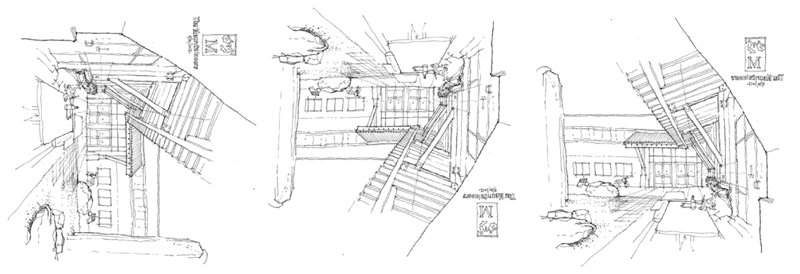

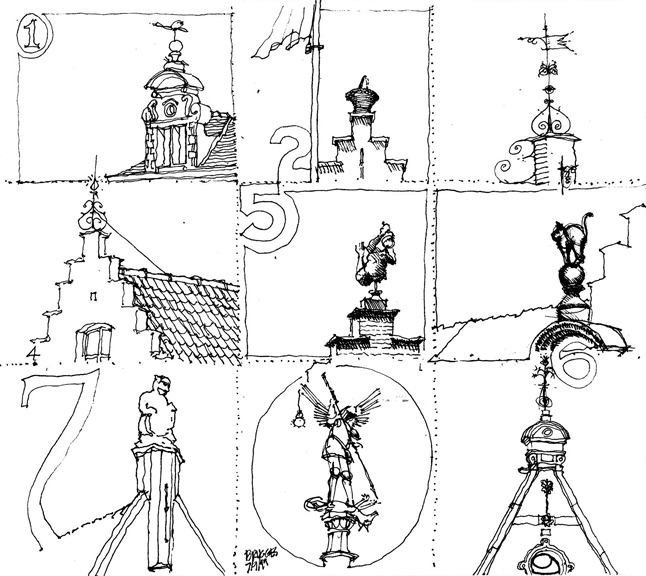

To help fill this gap between the printed book and hands-on instruction, I’ve been working with Nan-Ching Tai on an ebook on architectural sketching. The idea is to develop 40 or 50 focused lessons or modules that can be viewed in any order. While the text is still rough, I’ve been mocking up drafts using the Keynote presentation program, focusing on the content that consists of a combination of photographic analyses, examples of my own sketches, as well as Quicktime movies of sketches that I’ve done using the Brushes app on my iPad. Here is one such module. There’s more work to be done refining the modules, clarifying the text and captions, and adding more videos, but it’s been a fun project thus far.