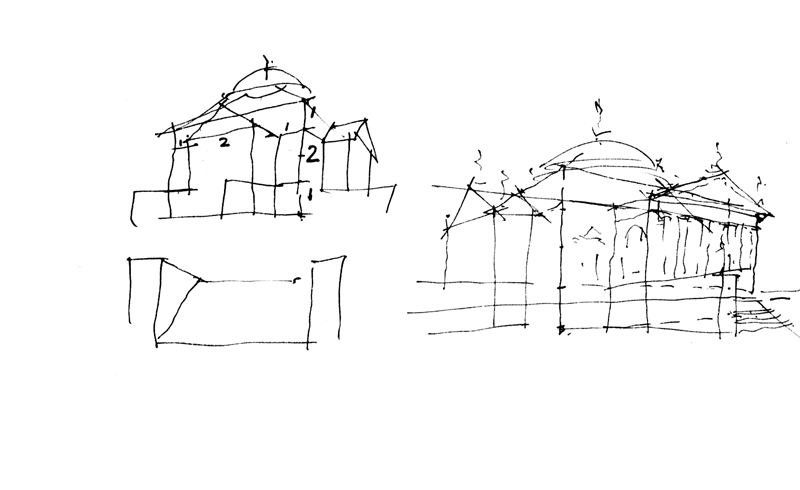

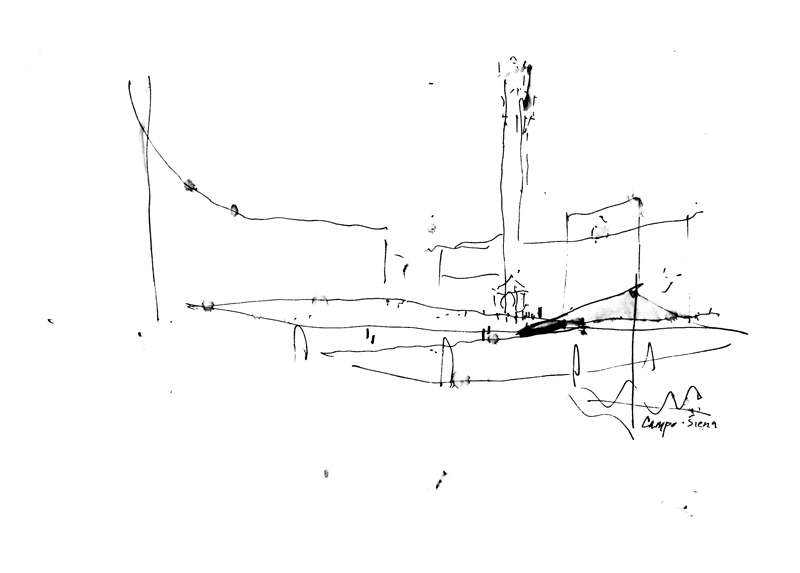

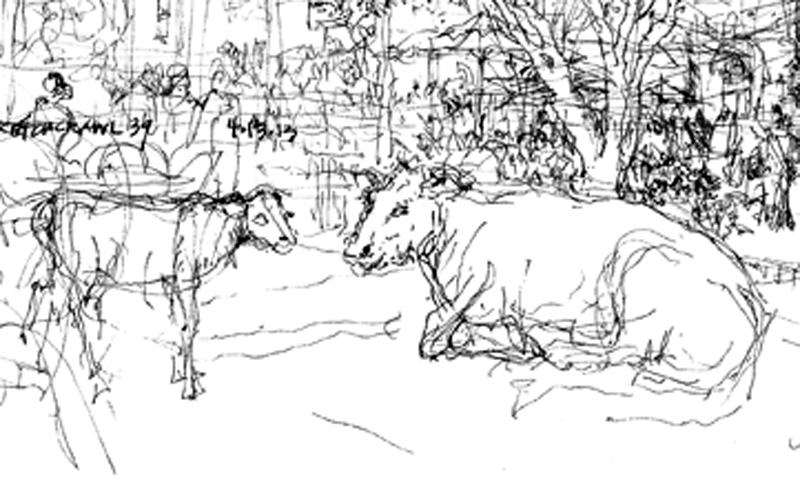

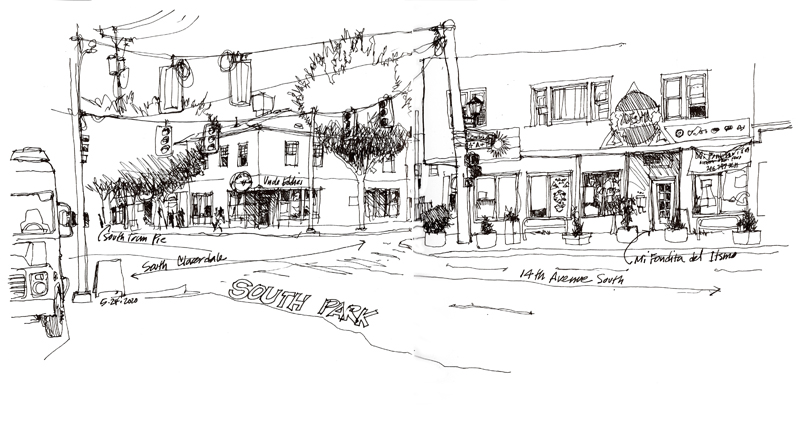

Above, the Lenin statue in the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle is seen from behind to reveal its placement on the edge of a triangular open space. Below it, a close-up view focuses on the statue itself, devoid of context. These sketches illustrate how, once a subject has been chosen, selecting a vantage point from which to view the subject influences the final outcome.

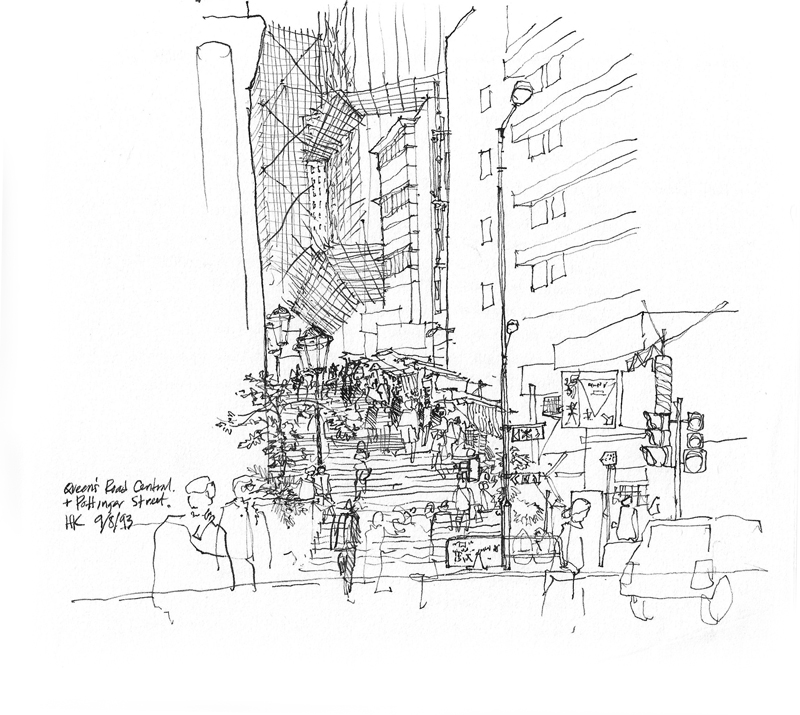

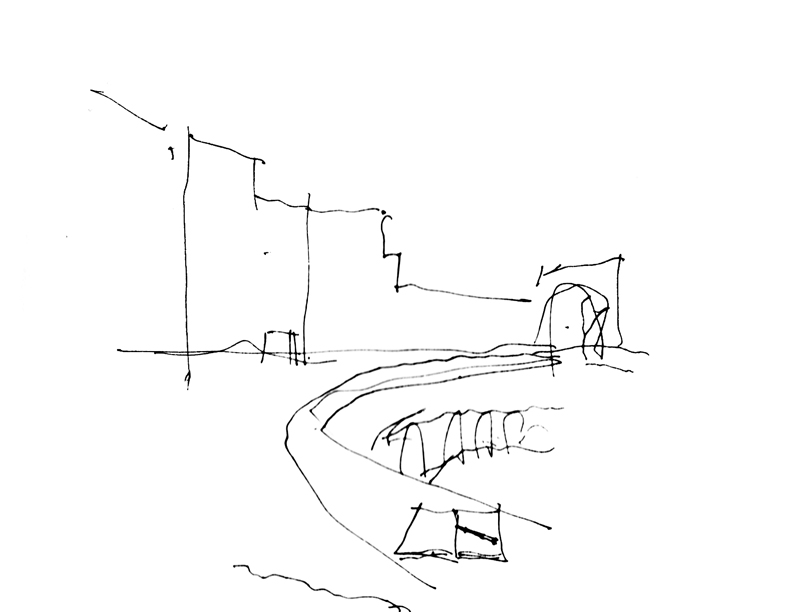

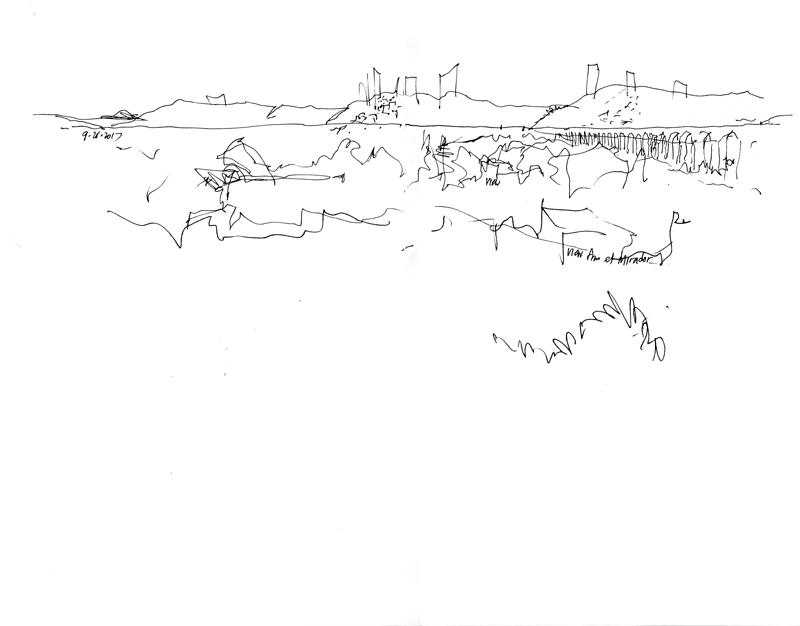

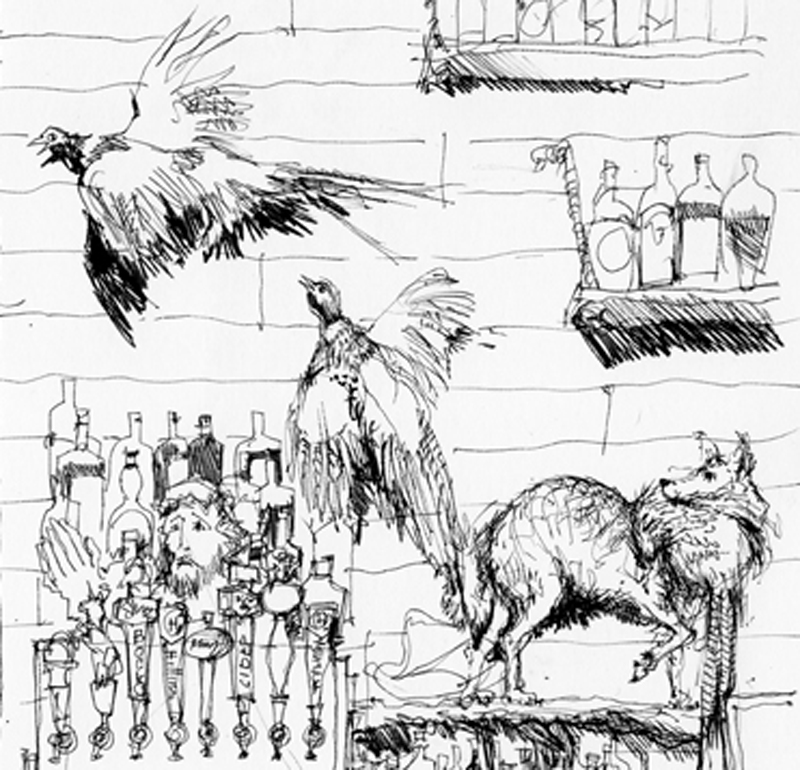

At times, it may be convenient, and more comfortable, to pick out a shady place to sit or stand. Other times, certain aspects of the subject might determine the desired angle of view.

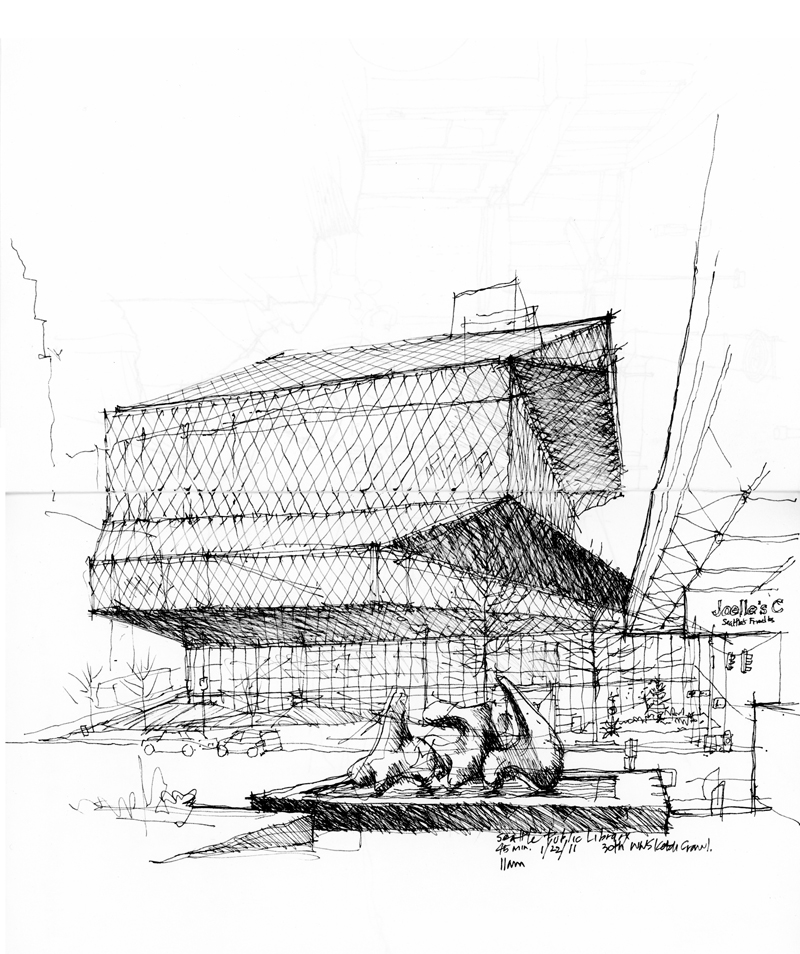

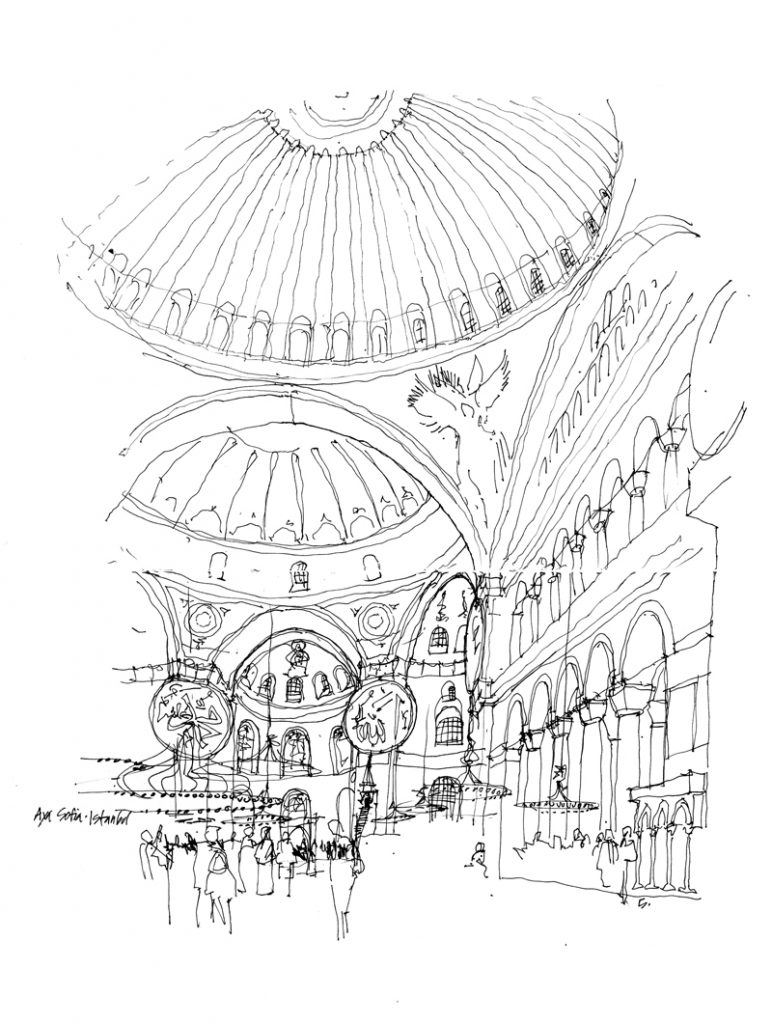

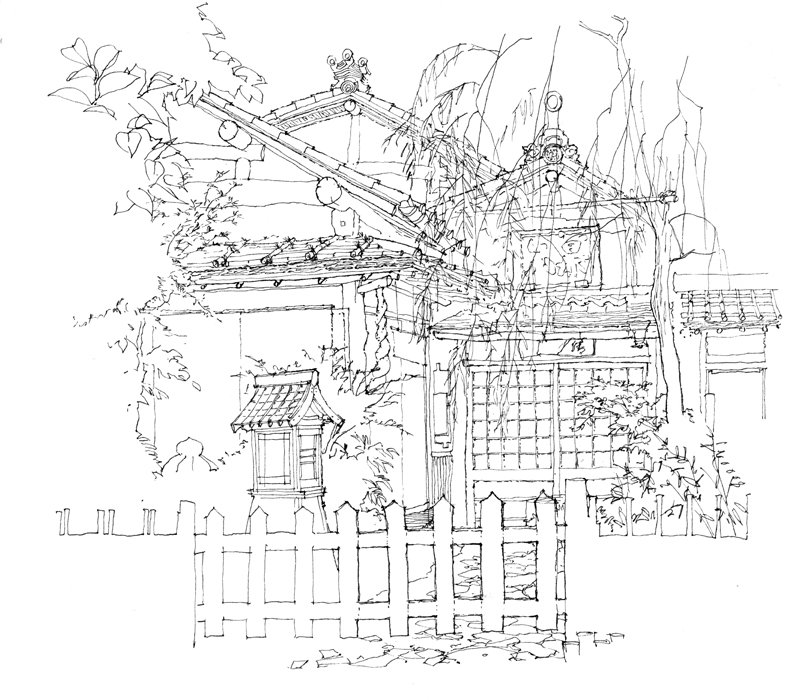

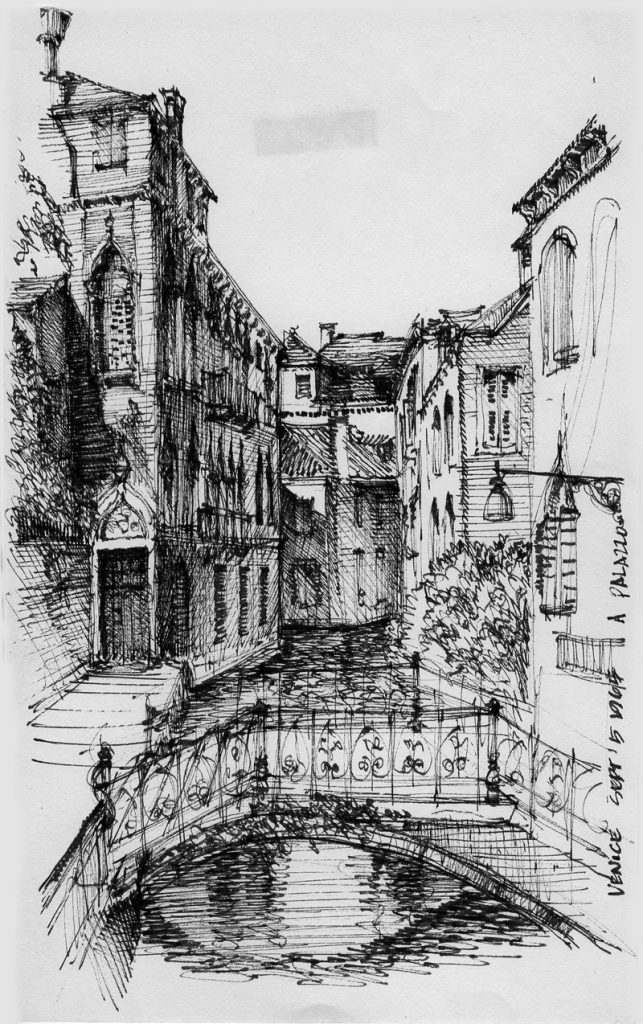

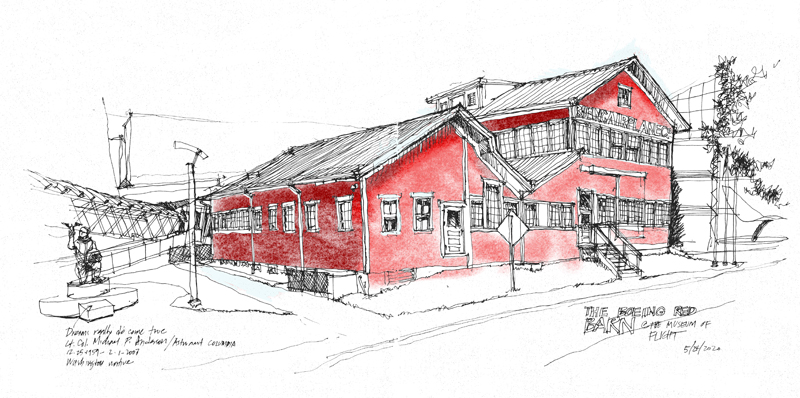

One may prefer a close-up, or to include more context, moving further back for a broader view. To focus on the symmetry of a space, we might position ourselves for a straight-on view, or to emphasize the three-dimensionality of the subject, we might select an oblique view

It usually time well spent to walk around a subject to select the best vantage point before touching pen or pencil to paper.