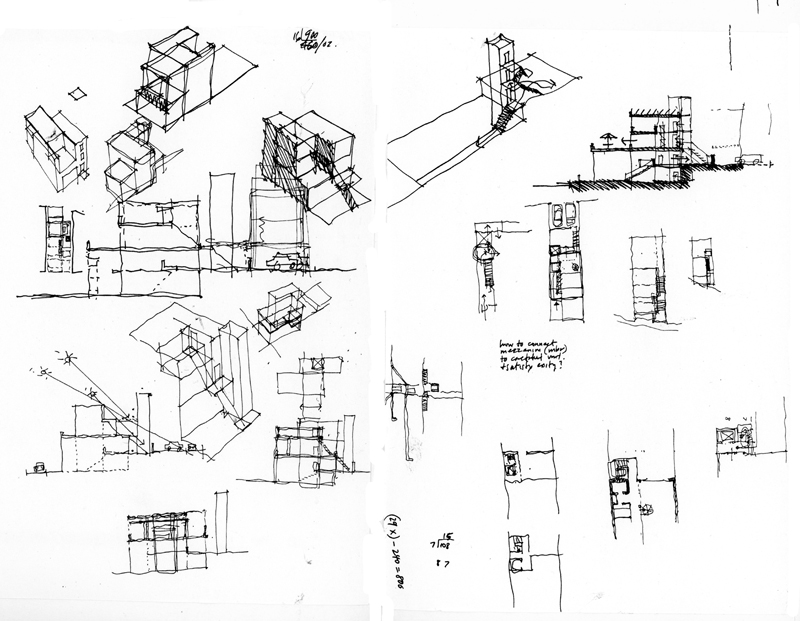

Stepping away from drawing from location for a while, I want to mention design drawings—drawings designers use to initiate and develop ideas and make them visible so that they can be acted upon. Whether we start with orthographic views, such as plans, elevations, and sections, before moving on to 3-dimensional views, or we begin the design process with paraline and perspective drawings, we should move back and forth from 2D to 3D and have the confidence that our visualizations are dependable predictors of future outcomes.

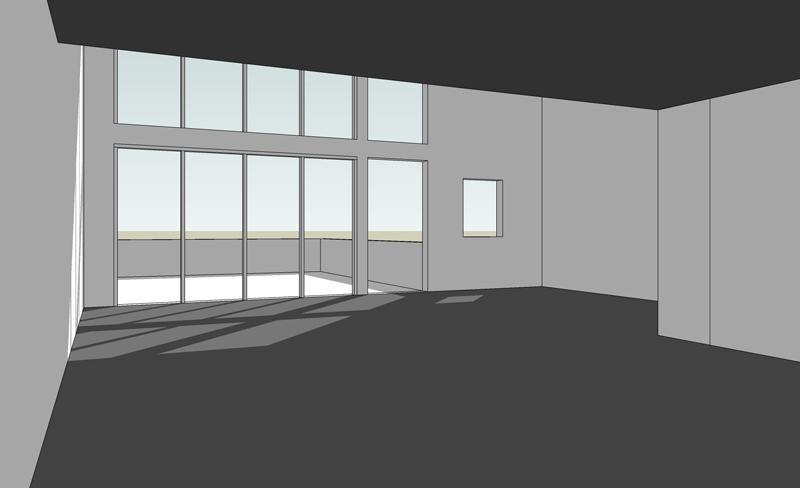

In an actual project nearing completion, it is interesting to compare a design study created in SketchUp with a photo of the constructed space. While not exactly identical, these two images are similar except for nuances of color and material. This shows the usefulness of preliminary studies to reliably foresee the result of our design decisions. Of course, these studies include not only graphic representations but also study models and prototyping. But for efficiency of time and fluency of thought, it is difficult to beat the graphic tools at our disposal.