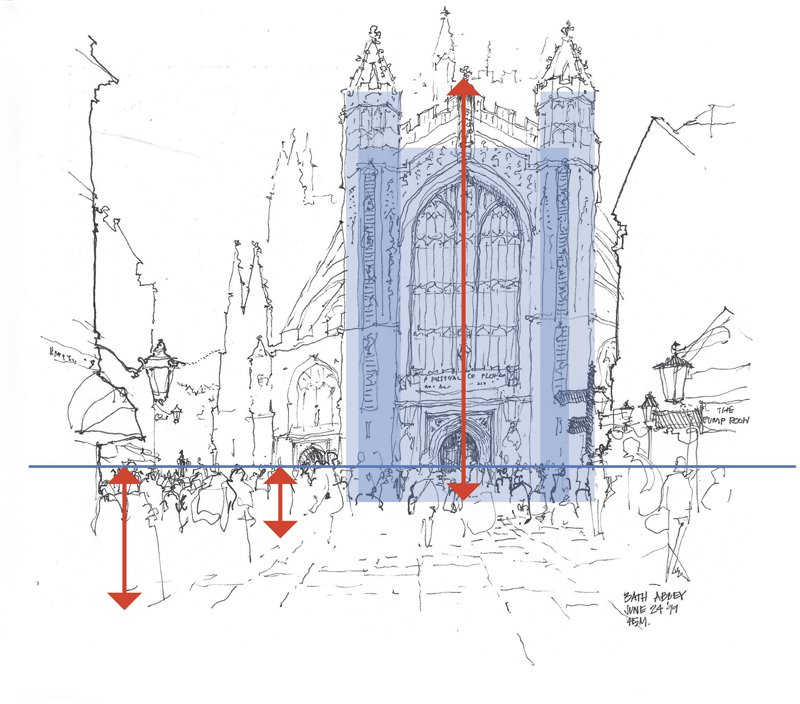

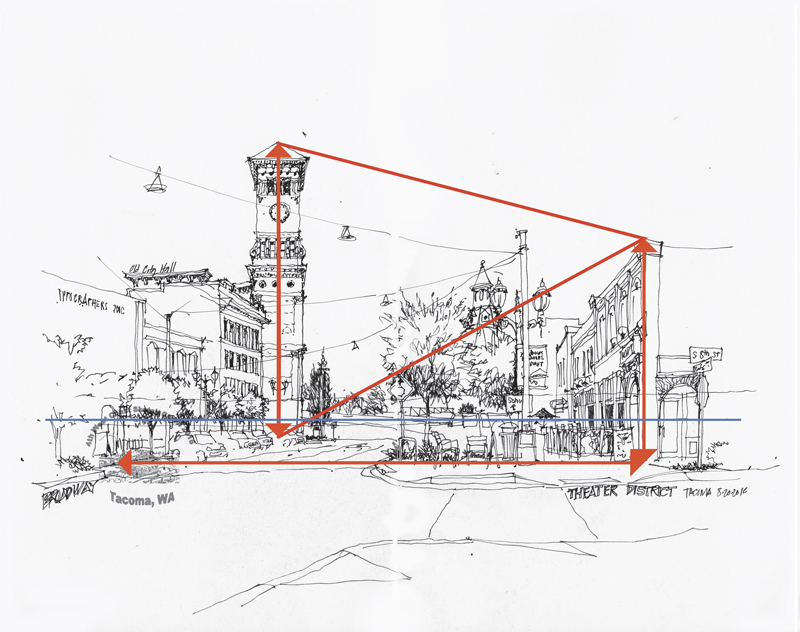

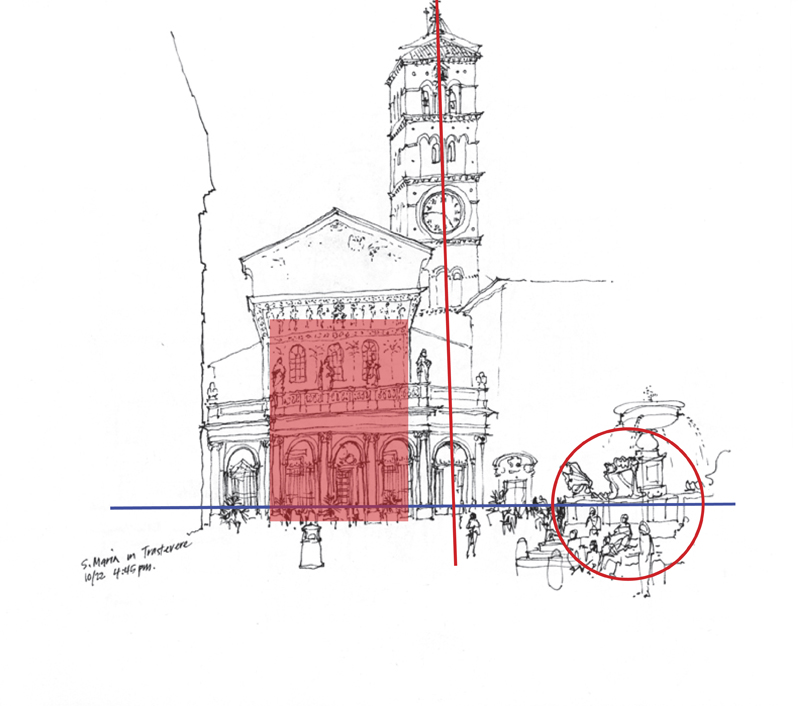

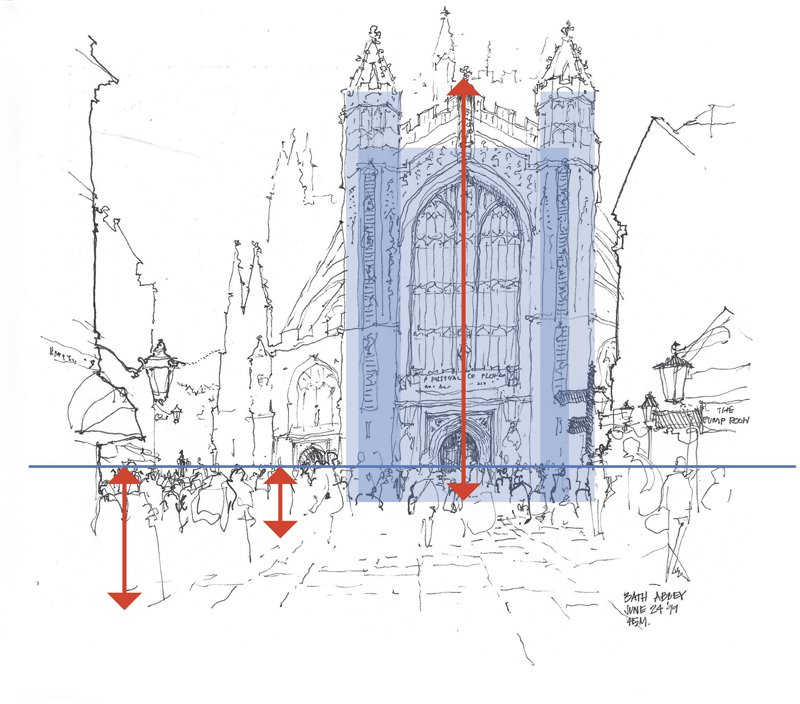

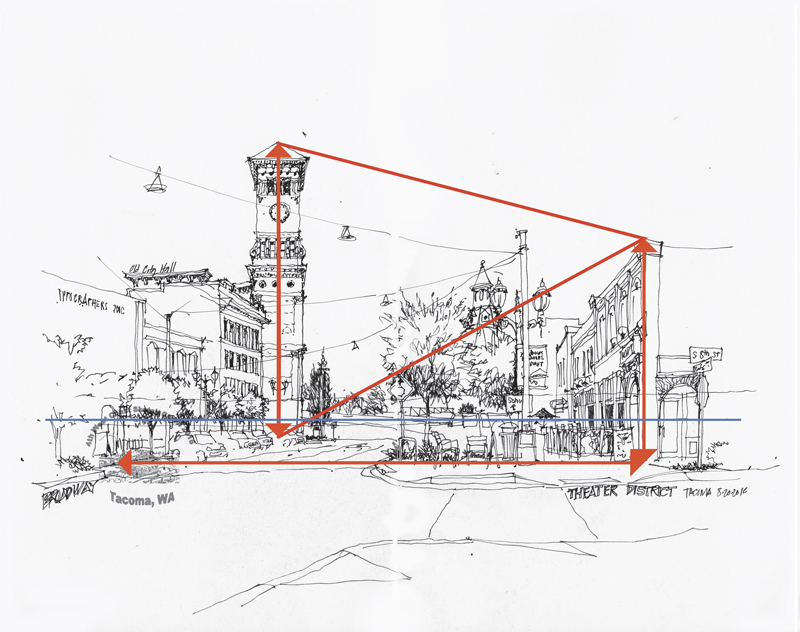

During drawing workshops, I often find myself pointing at things in scenes that students are drawing. What I’m doing is drawing attention to how things are related to each other—certain relationships of size, scale, proportion, and placement—in what we see before us. Paying close attention—not merely learning techniques—is one of the keys to drawing on location.

In his book Leonardo da Vinci, Walter Isaacson attributes many of Leonardo’s accomplishments to his acute powers of observation, which were not innate but honed with practice. And Isaacson believes that “to notice” is something we can all do if we make the attempt.

And so it is important to really focus on what one is seeing, not merely glance at the subject matter, before drawing. As I have often said during my workshops: “Look more and draw less.”

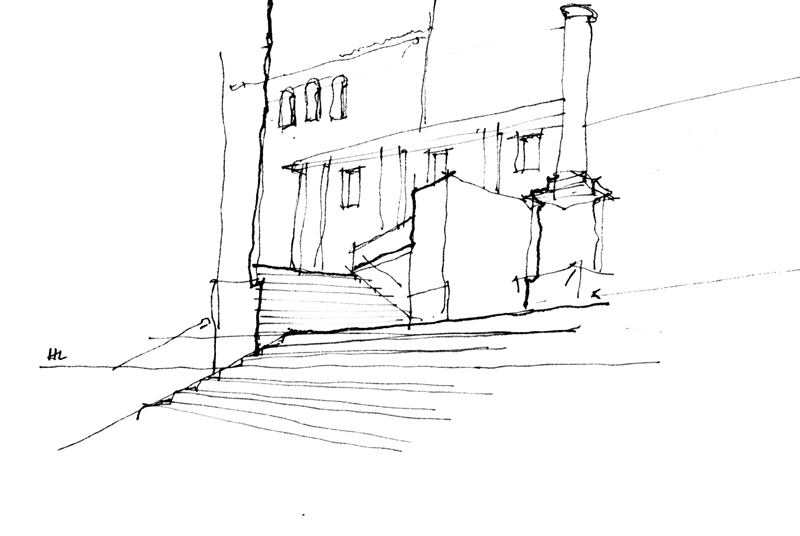

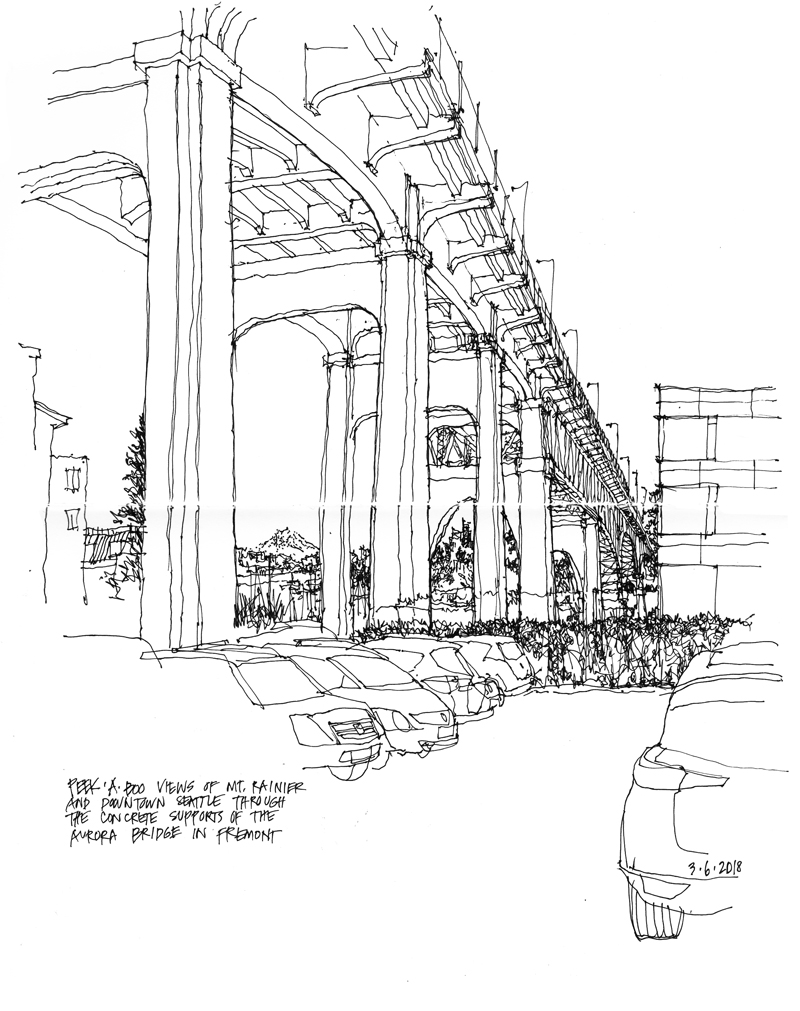

On our daily afternoon dog walk around the Fremont neighborhood, I’ve often noticed and admired this deeply layered scene. It offers a peek-a-boo view of Mt. Rainier and downtown Seattle through the openings of the concrete supports at the north end of the Aurora Bridge in Fremont.

On our daily afternoon dog walk around the Fremont neighborhood, I’ve often noticed and admired this deeply layered scene. It offers a peek-a-boo view of Mt. Rainier and downtown Seattle through the openings of the concrete supports at the north end of the Aurora Bridge in Fremont.