In the 1950s, the psychologist J.J. Gibson outlined a number of cues to depth perception. A few rely on our binocular vision and therefore do not apply to 2-dimensional drawings and paintings. Others, however, are psychological rather than physiological in nature. As such, these depth cues are pictorial in nature and are applicable to drawing and painting on a 2-dimensional surface. In the following, I try to use simple terms and snippets of my own drawings and photographs to illustrate each of the depth cues that I consider to be relevant to drawing on location.

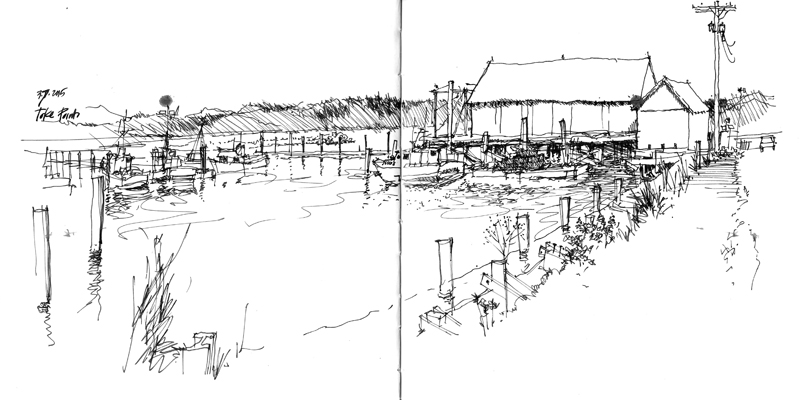

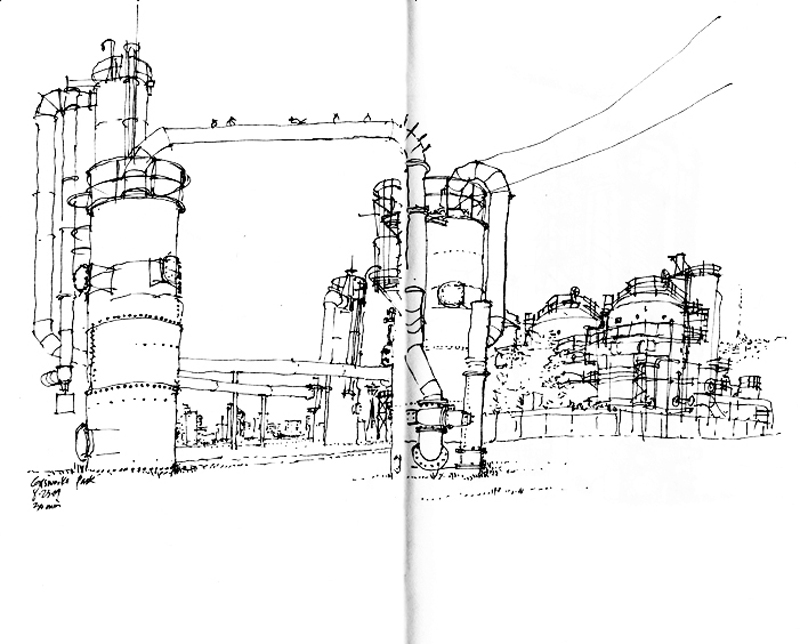

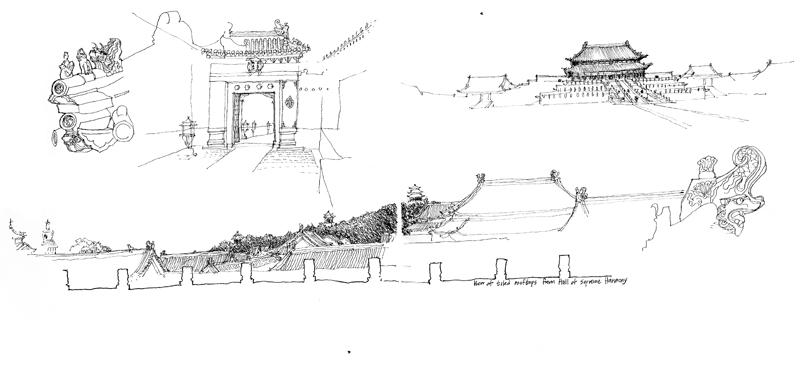

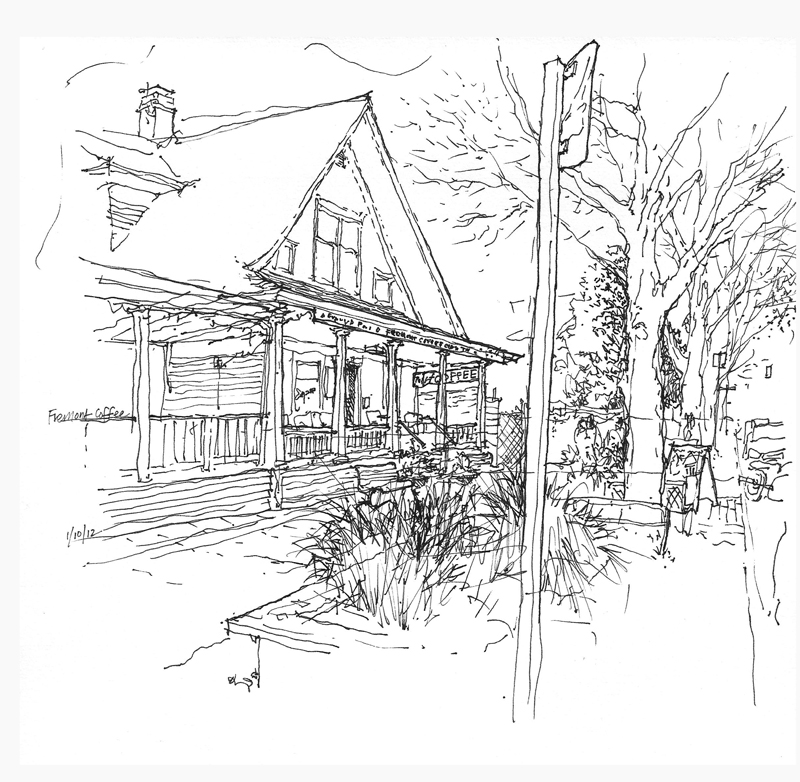

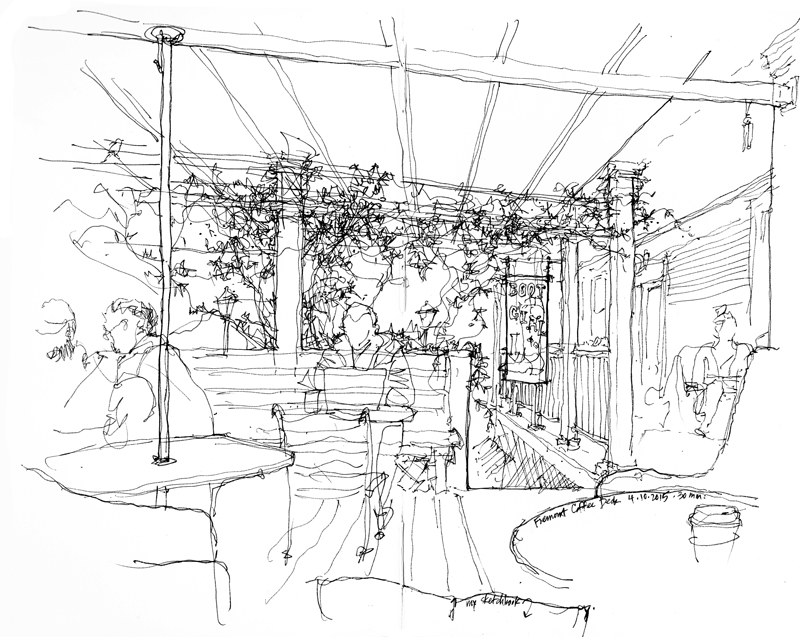

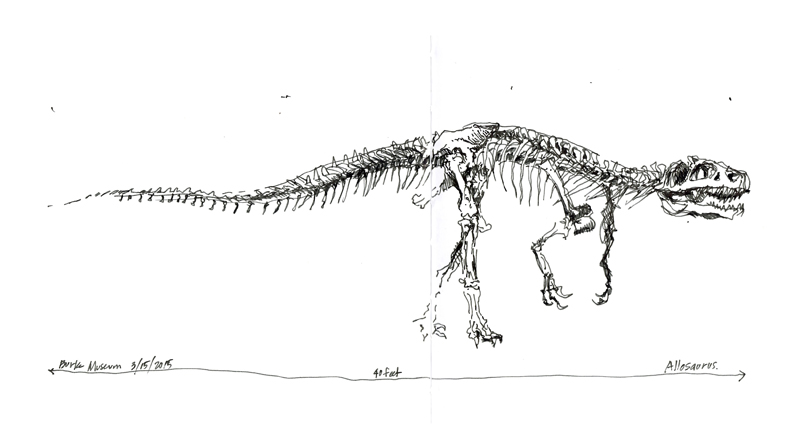

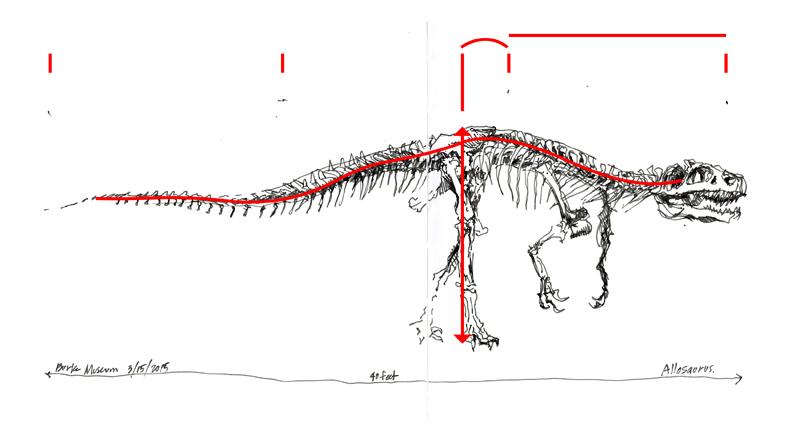

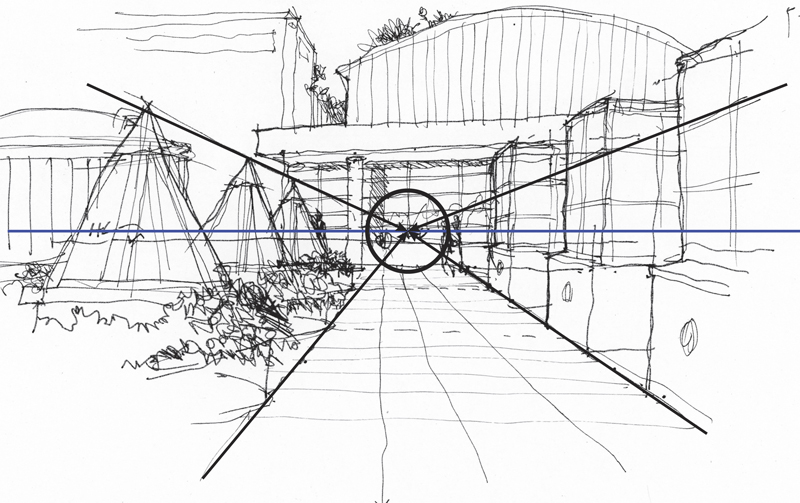

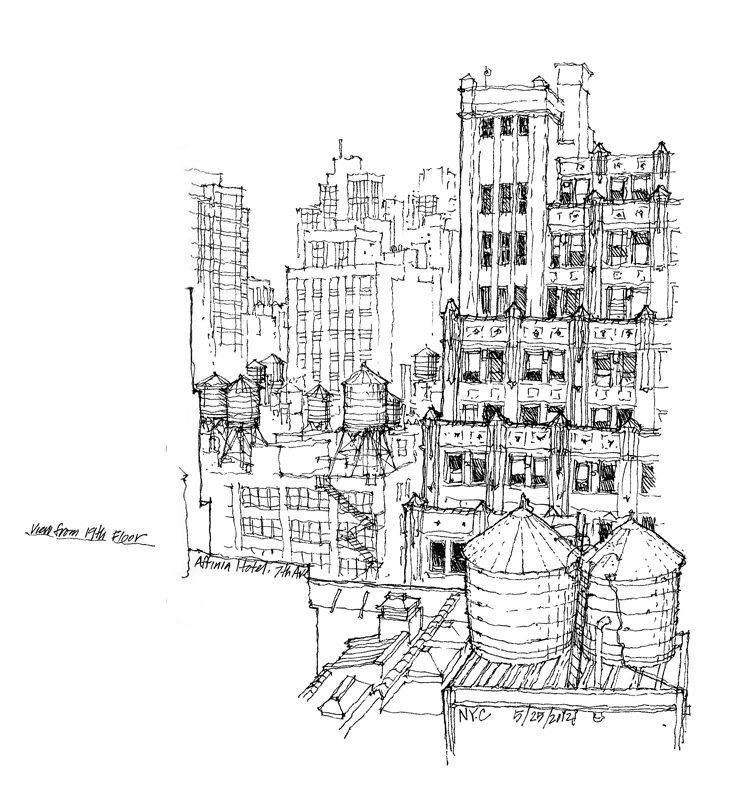

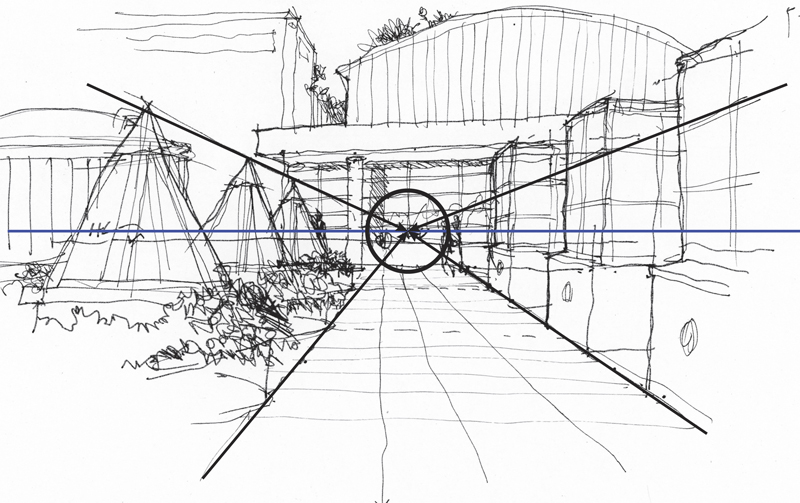

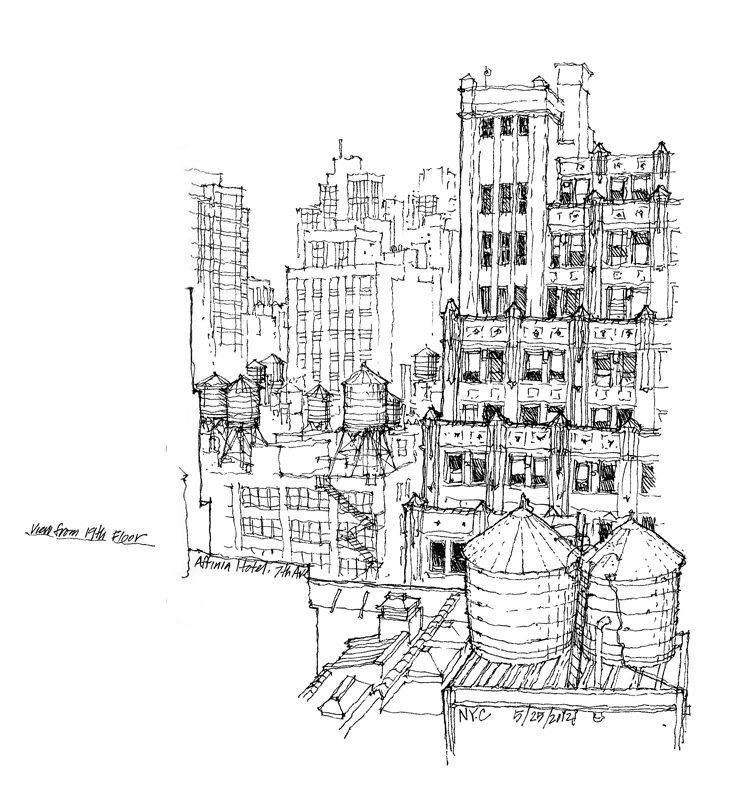

Convergence of parallels: This is a key characteristic of linear perspective in which parallel lines appear to converge as they recede into the distance. Despite the usefulness of the other depth cues, linear perspective remains the structural scaffolding upon which to build a sense of spatial depth on the page.

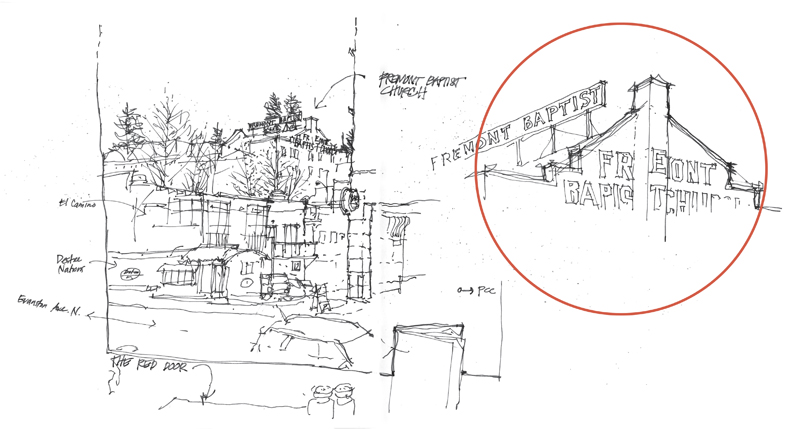

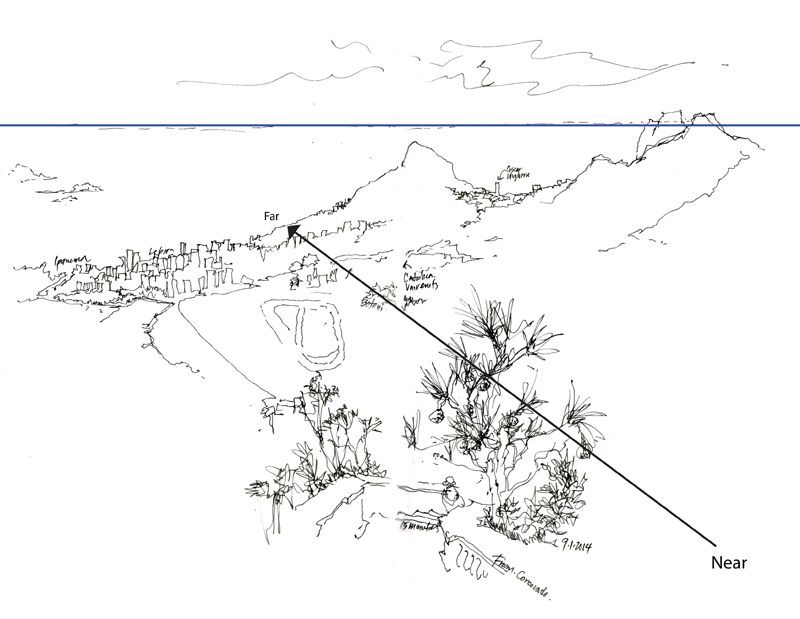

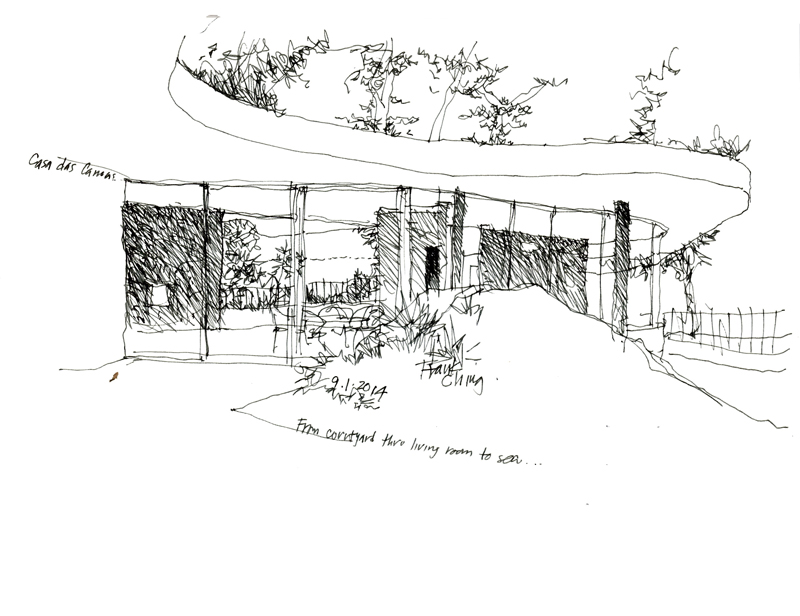

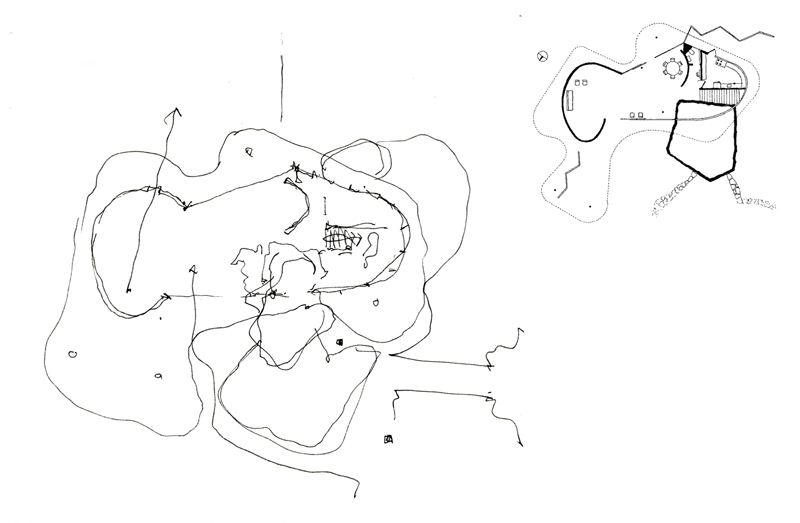

Overlap: Near objects overlap or partially block the view of objects farther away. Locating effective overlaps can be useful in selecting a viewpoint and composing a drawing.

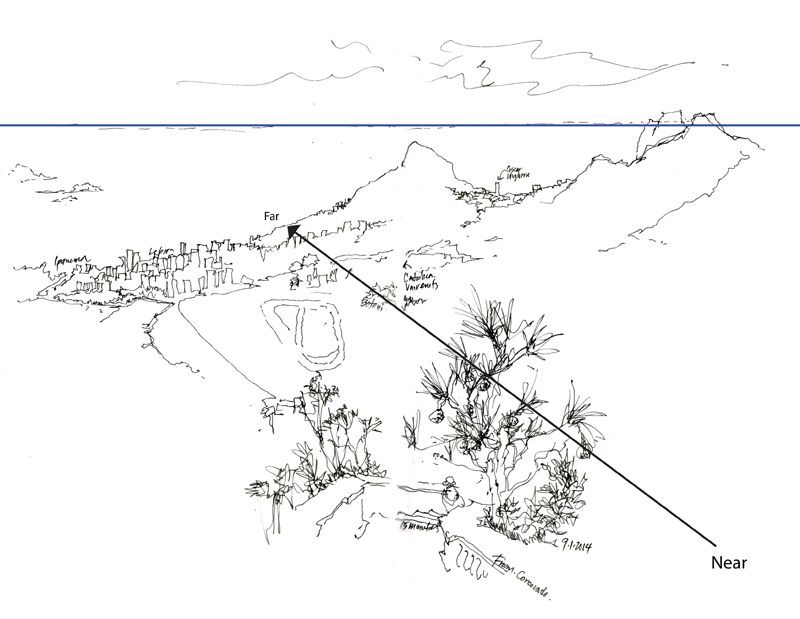

Position relative to the horizon: Objects below our eye level rise toward the horizon as they recede; objects above our eye level descend toward the horizon as they recede.

Relative size: Objects known or assumed to be of similar size appear to shrink in size with distance from the observer.

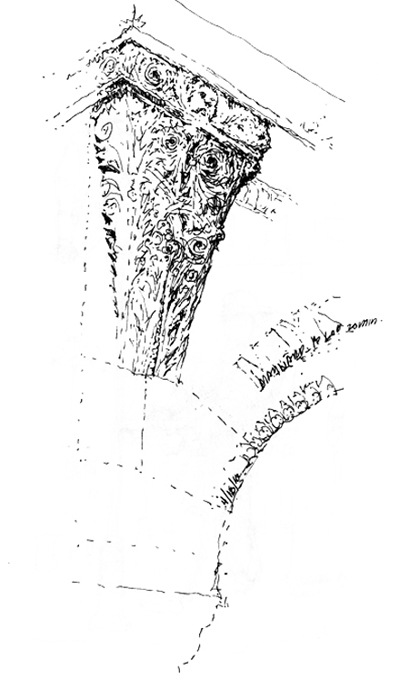

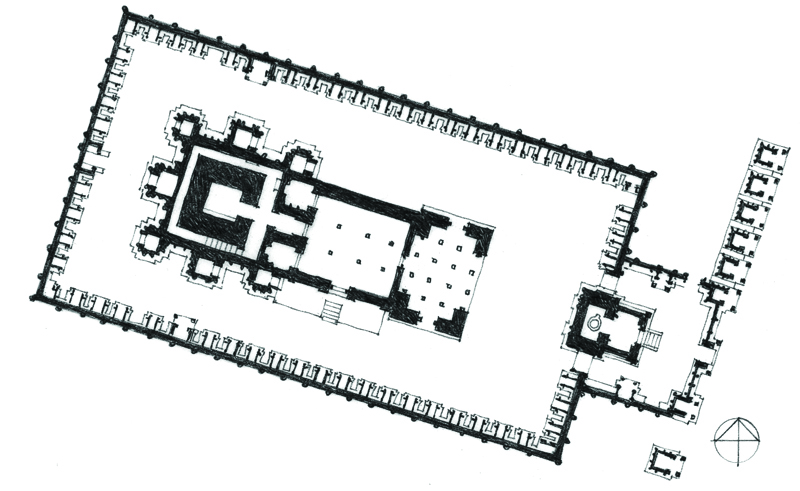

Texture gradient: Surface texture appears to get finer and smoother with distance from the observer.

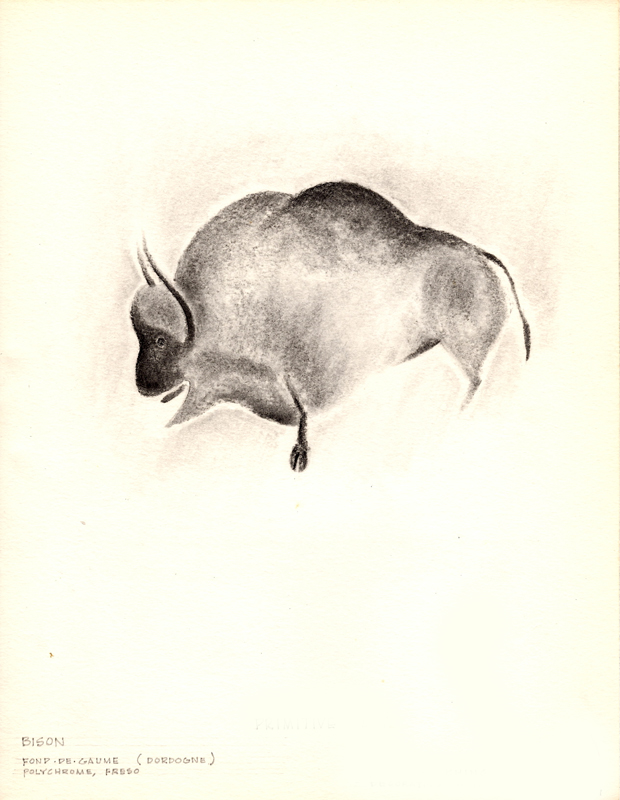

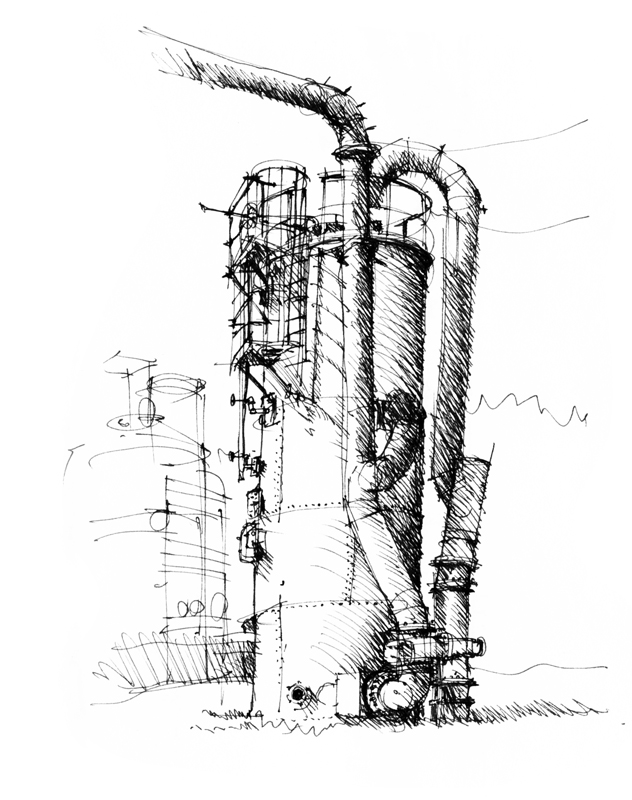

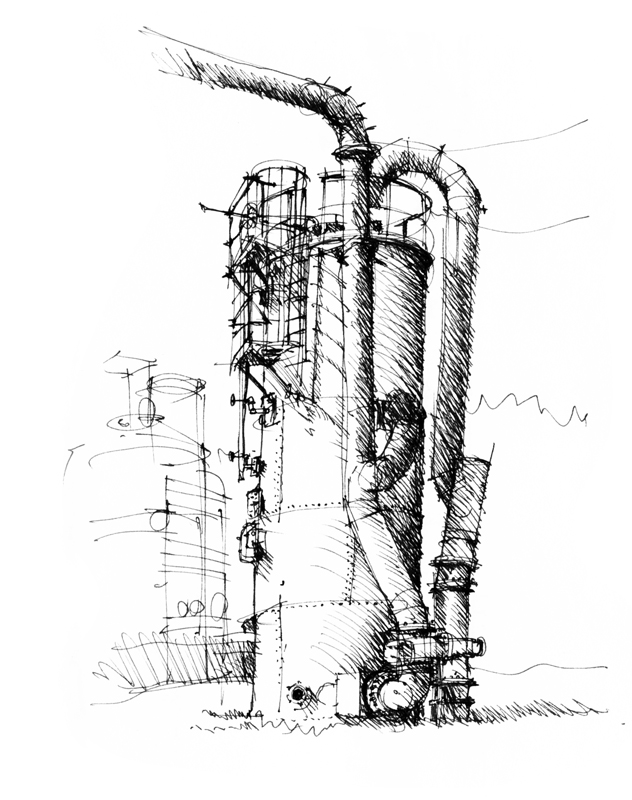

Shading and shadows: Contrasts in light and dark can convey the shape, form and depth of objects.

Aerial perspective: Particles in the atmosphere affects the color and visual acuity of objects at varying distances from the observer; distant objects appear grayer or bluer and less distinct than nearer objects.

As we can see, scenes more often than not comprise a number of these depth cues operating simultaneously. Seeing how these depth cues occur in our real-life perception can aid our understanding of why things appear as they do, counter to what we know of the things we draw, which are often in conflict.