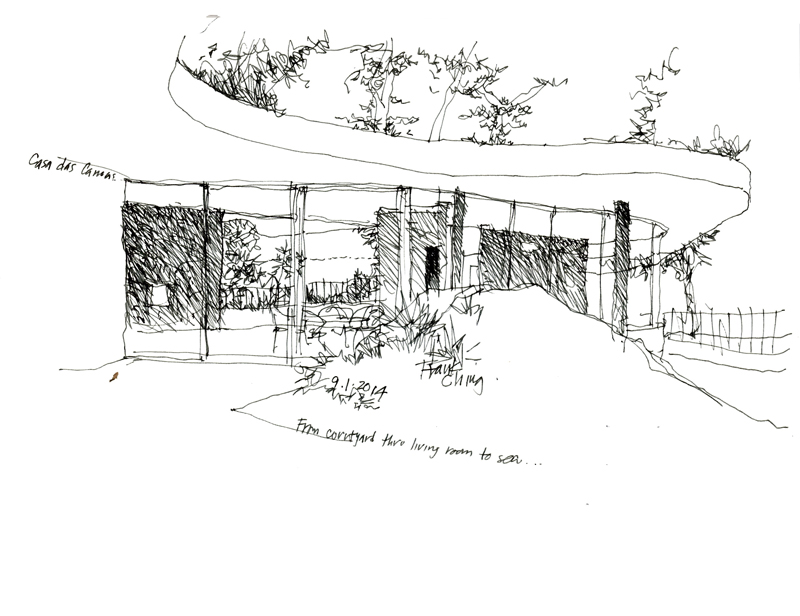

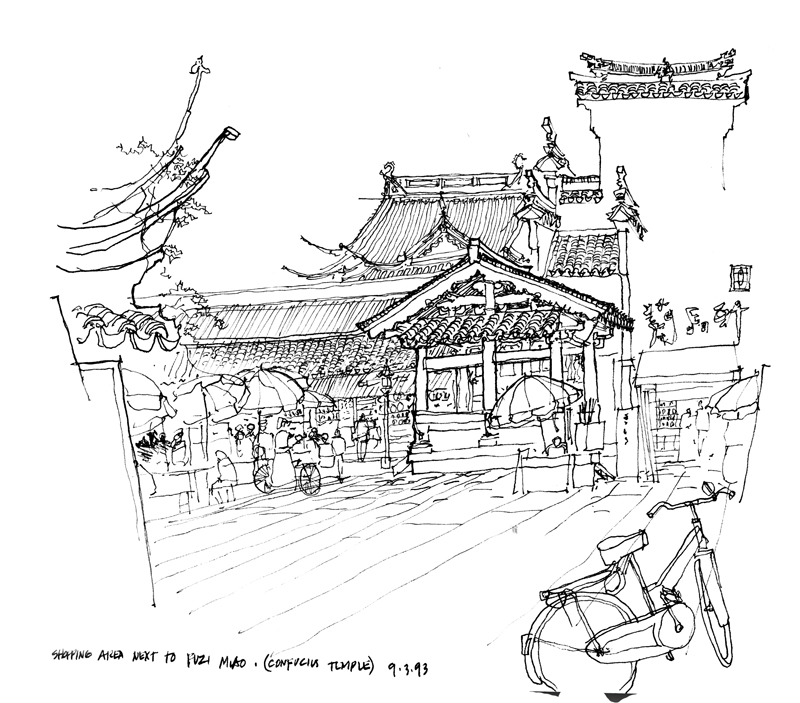

While in Rio de Janeiro a month ago, we had the opportunity to visit Casa das Canoas, the first residence designed by Oscar Niemeyer in 1952. It is a true gem, nestled in a beautiful hillside setting and displaying the characteristic flowing lines of Niemeyer’s architecture. Thanks to Caique Niemeyer, Oscar’s grandson, for allowing us the privilege of touring this fine example of modern architecture.

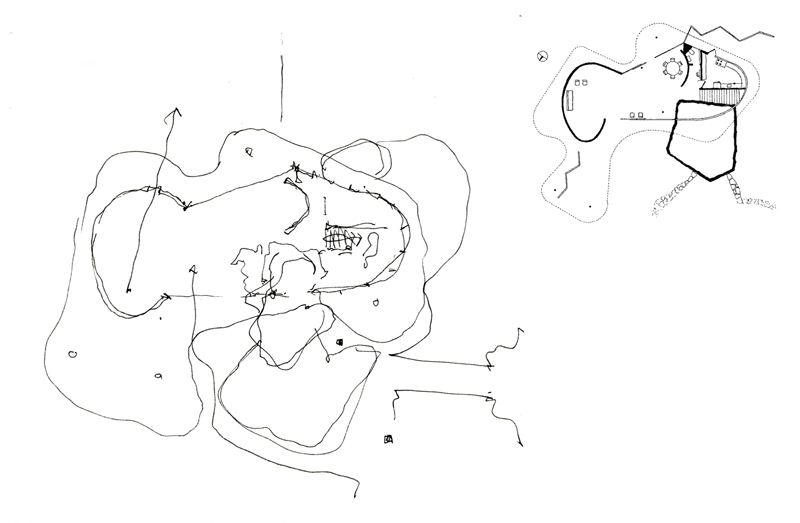

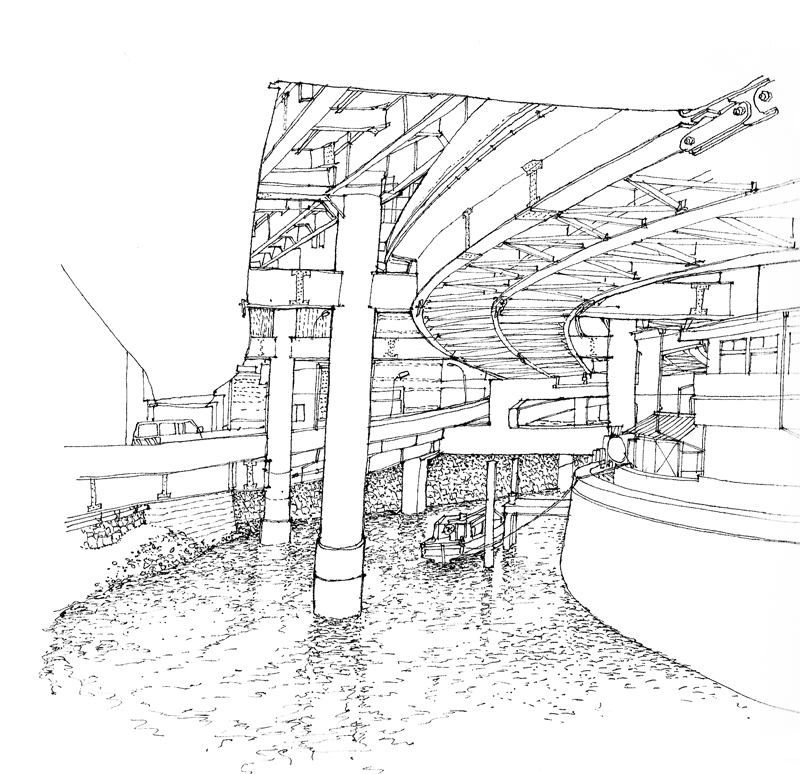

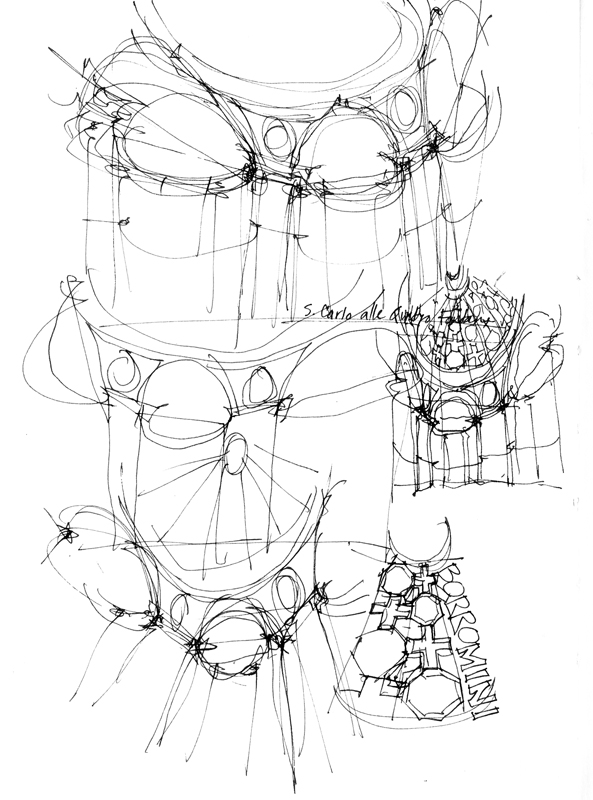

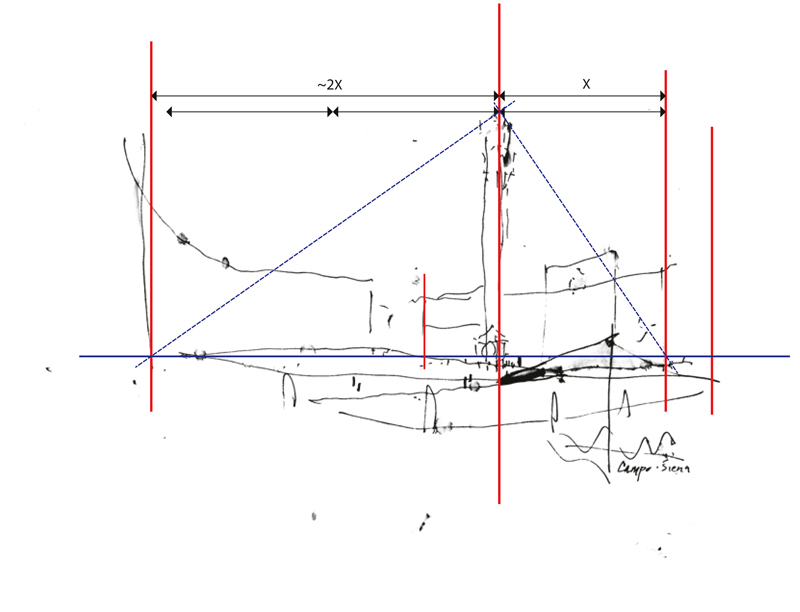

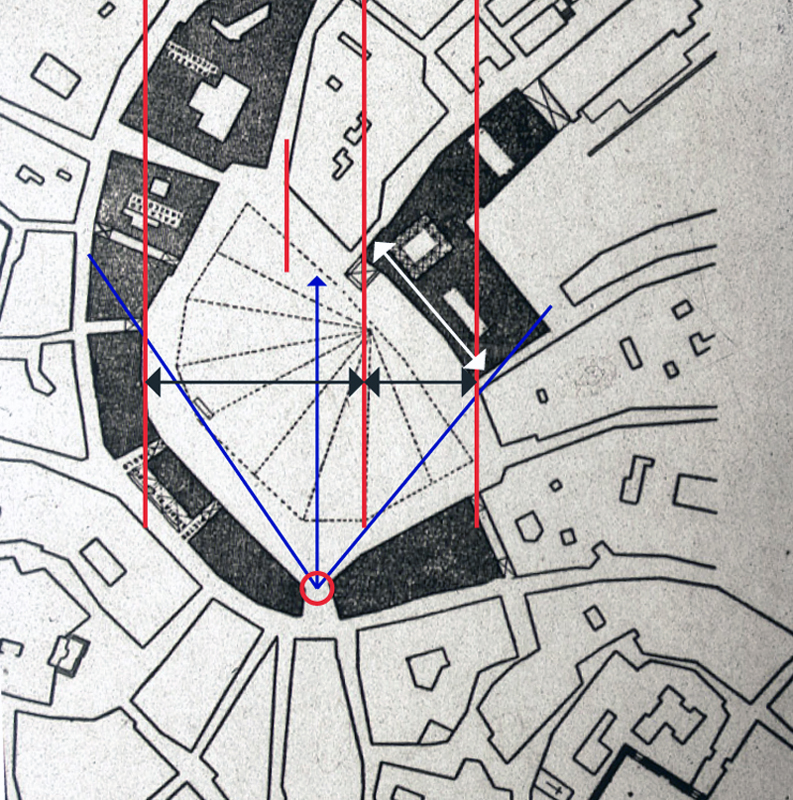

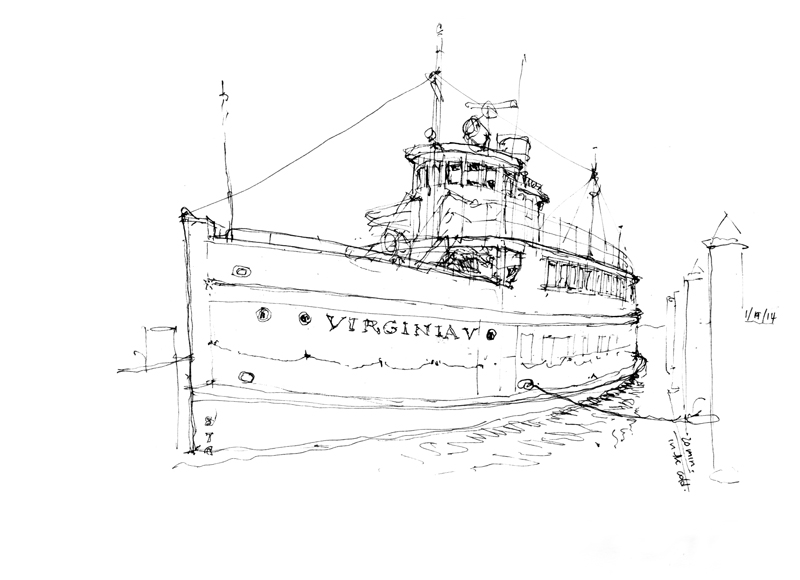

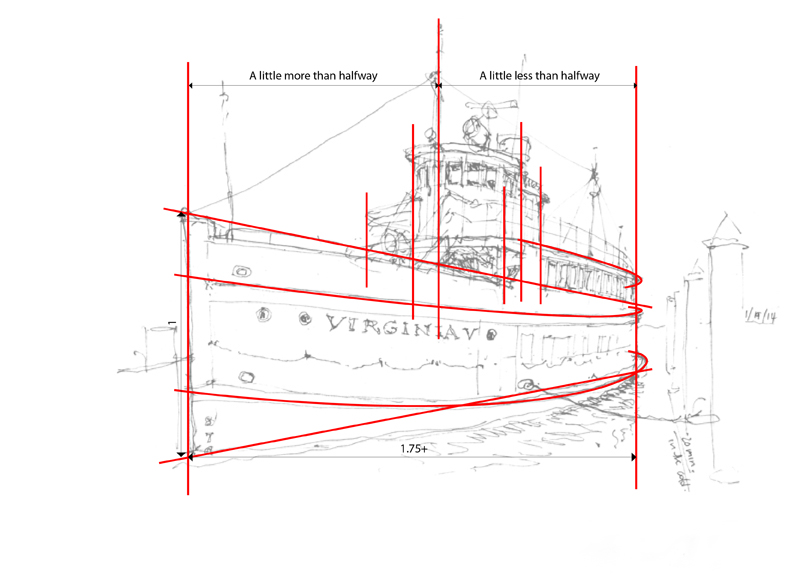

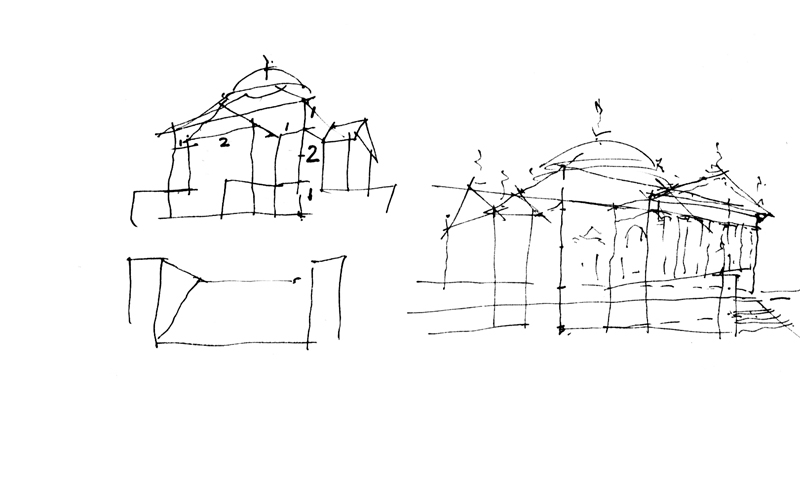

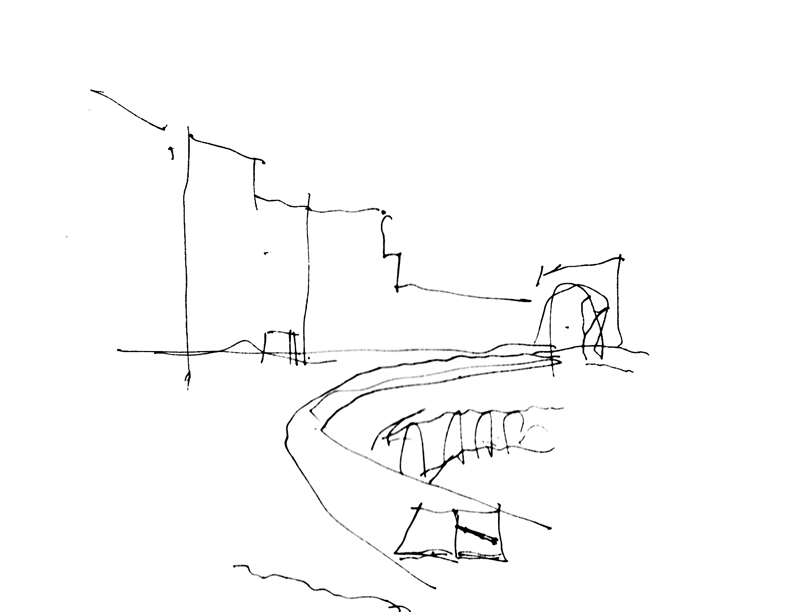

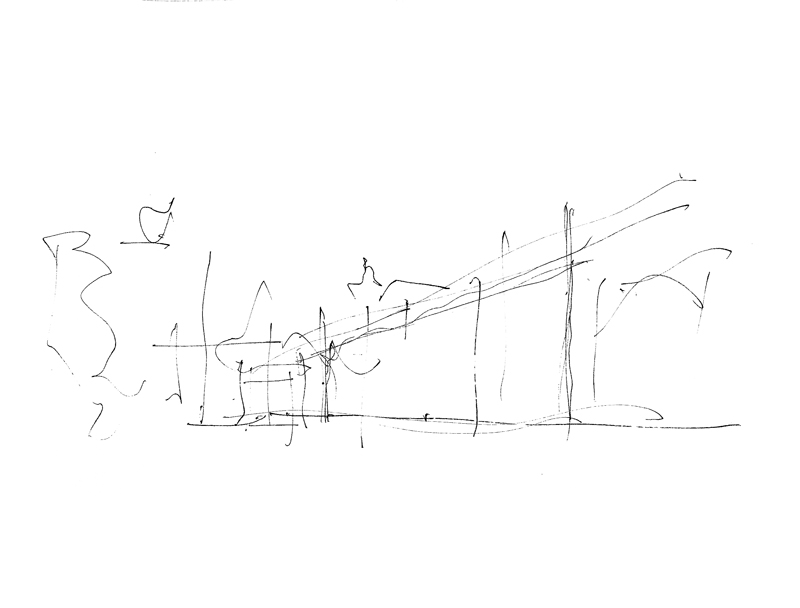

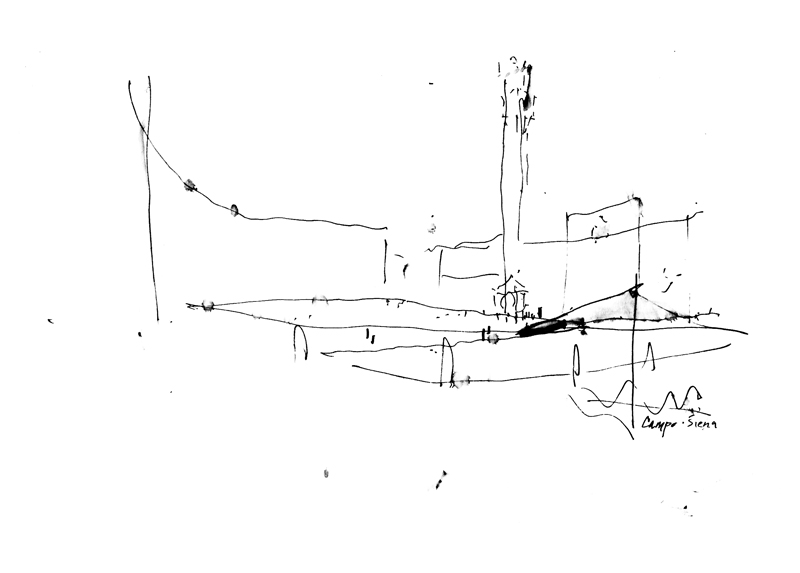

After doing a few sketches of the exterior and interior of the deceptively simple structure, I attempted to draw a plan to try to understand the two-dimensional origin of what I saw in three dimensions.

To verify my plan, I perused several books on the architecture of Oscar Niemeyer but none contained a plan of this house. Upon returning to Seattle, I did an internet search and found this plan drawn by Jeff Hottinger, which is included next to the plan I drew.

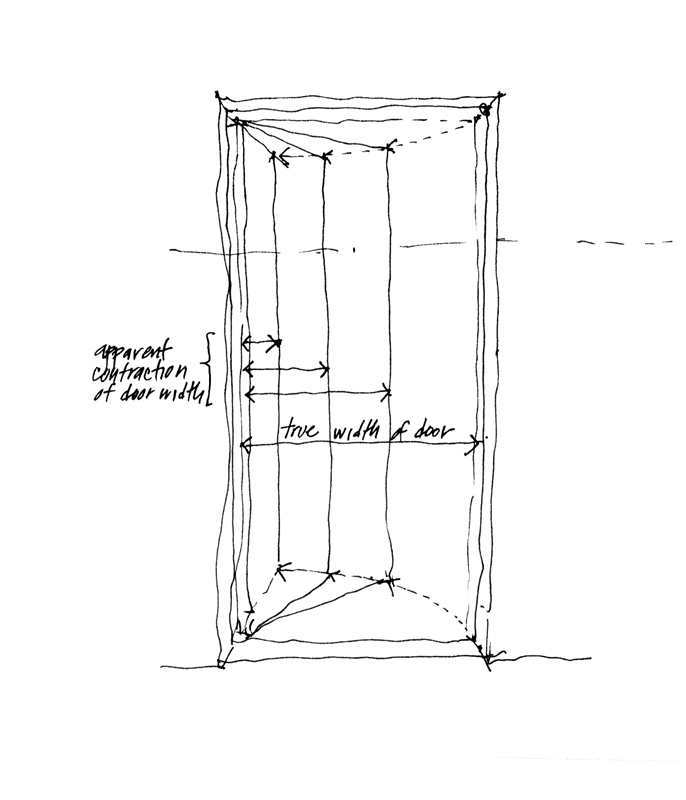

In this age of digital 3D modeling where much design thinking and decision-making is made from a perspective viewpoint, it is still a useful mental exercise to try to imagine the orthographic relationships that plans and sections reveal and which perspective views do not. As designers, we should be able to think two-dimensionally as well as three-dimensionally.