The few times I had the privilege of teaching in Rome, we always scheduled a field trip to the Amalfi Coast, stopping in Cuma, Naples, and Pompeii before arriving in Amalfi and using it as a base to visit Ravello and its Villas Cimbrone and Rufolo as well as the Greek site of Paestum further down the coast.

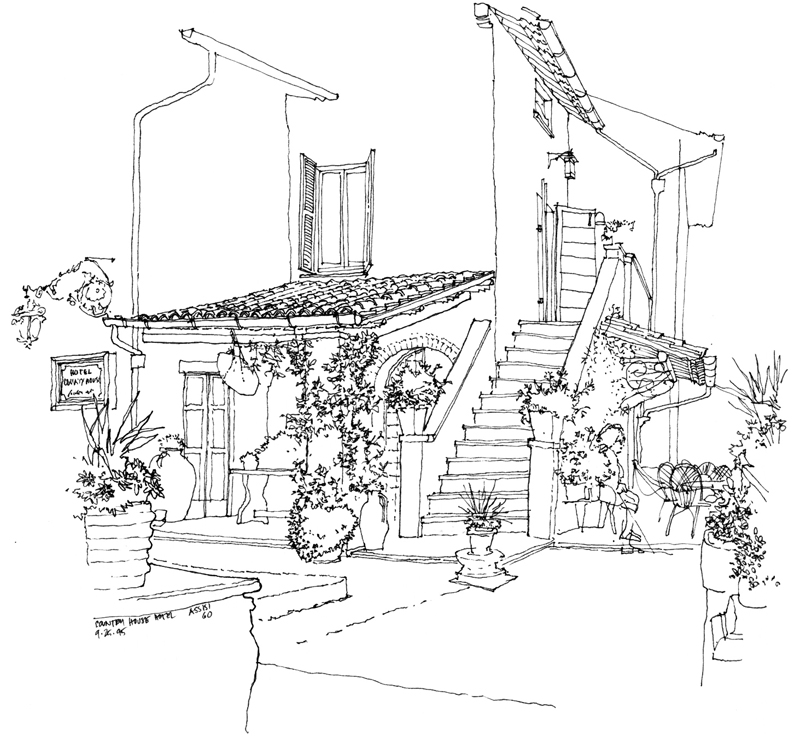

In 2000, we were able to stay in placid Ravello at the Hotel Parsifal, a former monastery built in 1288 on the edge of town. This is a view of my corner room and terrace, which overlooked the Amalfi Coast and the Tyrrhenian Sea.

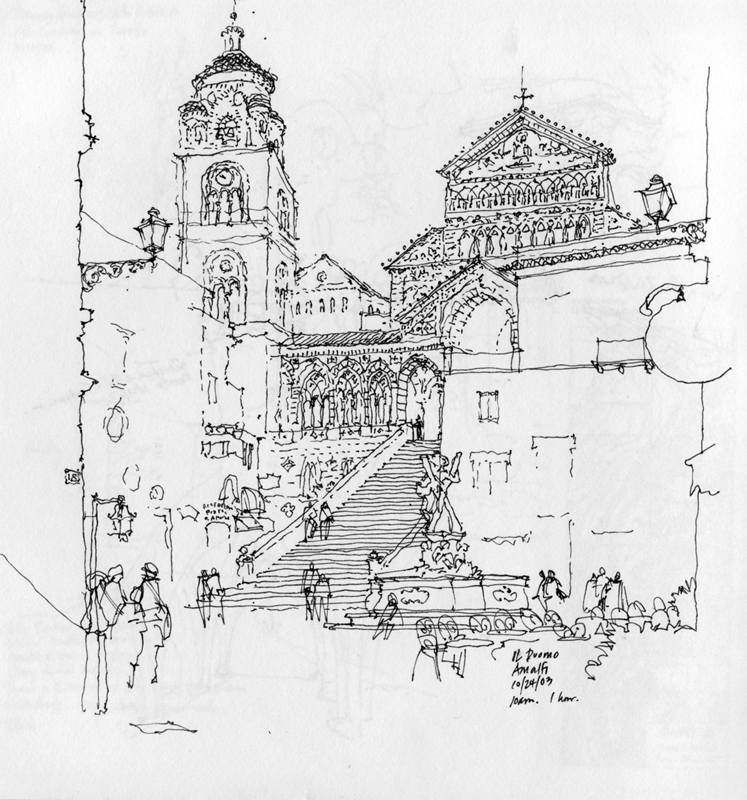

The other times we stayed at the Hotel Lidomare in the coastal town of Amalfi, just off the main piazza from which one sees this view of the Duomo. A broad stairway leads up to a striped marble and stone entrance arcade, surmounted by a pedimented facade with a mosaic tympanum. Off to the left is a Romanesque bell tower and tiled cupola typical of the area. I simply outlined the foreground and surrounding structures to contrast with the ornamentation of the cathedral.

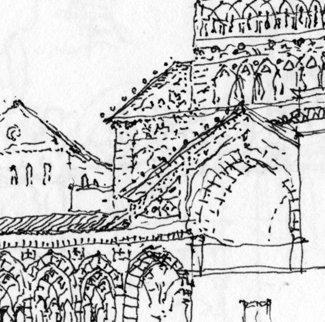

While the drawing appears to be very detailed, this enlarged portion shows that drawing has the unique ability to suggest without having to exactly reproduce what a photograph might capture. As I wrote a few months ago, this is the magic of hand drawing—”to suggest to the mind’s eye a scene that we recognize. The whole is truly greater than the sum of the parts.”