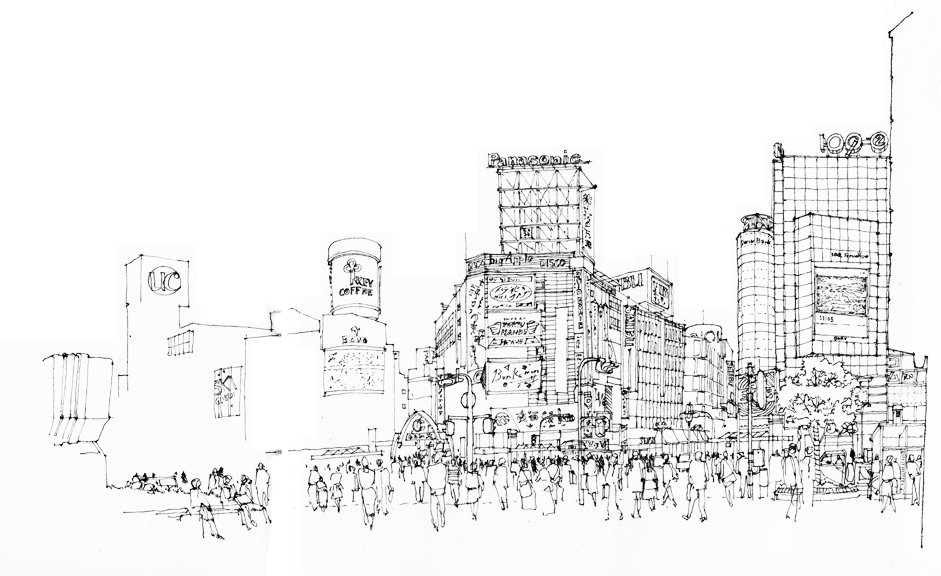

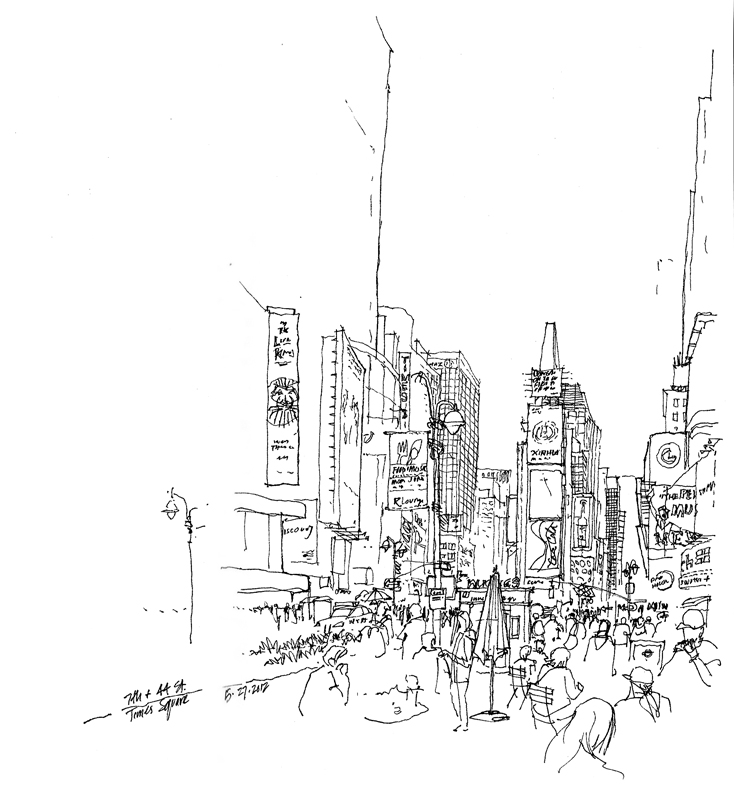

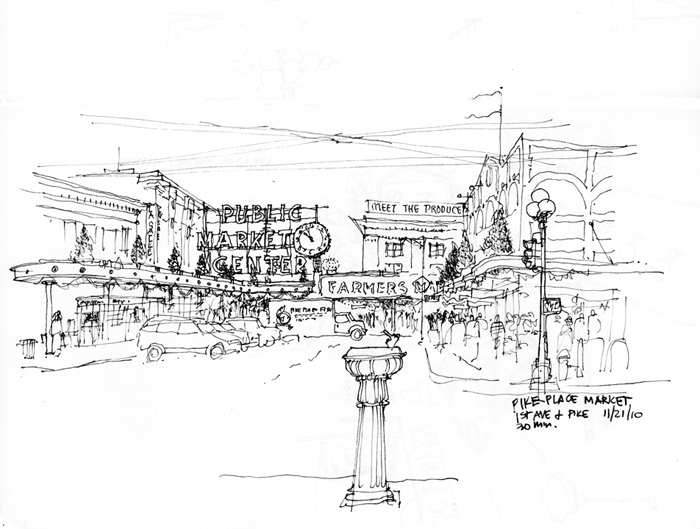

Most major cities have one or more hubs where people gather because of the fortuitous mix of transport systems and civic, cultural, and commercial amenities. Here are views of three.

The first is of Shibuya, a center of shopping and nightlife located just outside one of Tokyo’s busiest railway stations. The bustling intersection is dominated by large video news and advertising screens and a sea of people using the “scramble” mode to cross in every direction at the same time while all vehicular traffic is stopped.

The second is of Times Square in the entertainment and Broadway theater district of midtown Manhattan. Again, the brightly lit environment is dominated by the gathering mass of people at ground level and the visual onslaught of oversized electronic billboards.

The third is of the Pike Place Market in Seattle. Though not of the scale of Shibuya and Times Square, this market entrance still serves as an iconic attraction for both Seattleites and visitors from abroad. In each case, it is not the architecture of individual buildings but rather the urban spaces created by the architecture and the overhead visuals that make these attractive urban hubs.