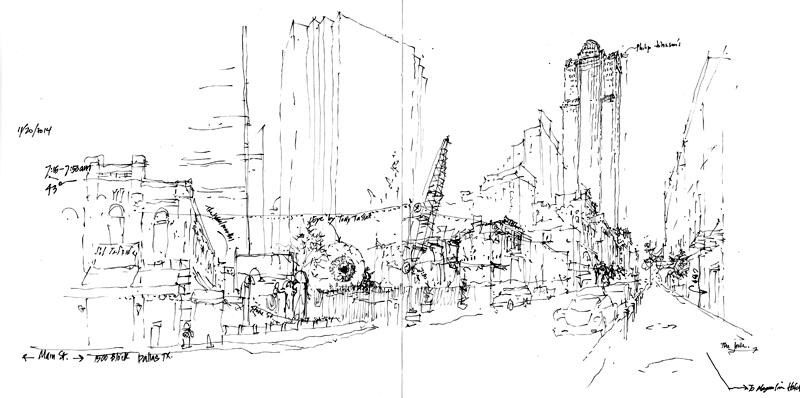

During a brief visit to Dallas recently, I woke up early one morning and sketched this view of the city’s Main Street. To capture the feeling of a city in transition, this panorama takes in the high-rises of a typical downtown, including the Bank One Center by Philip Johnson and John Burgee (now the Comerica Bank Tower) on the right; one of the many older structures being torn down to make way for new projects in the middle; and the Laumeier Sculpture Park featuring the Eye, a 38-foot diameter sculpture by Tony Tasset. What surprised me was how roughly the sketch developed until I realized that the ink in my pen was not flowing as freely as it normally does because of the 43° weather.

Monthly Archives: November 2014

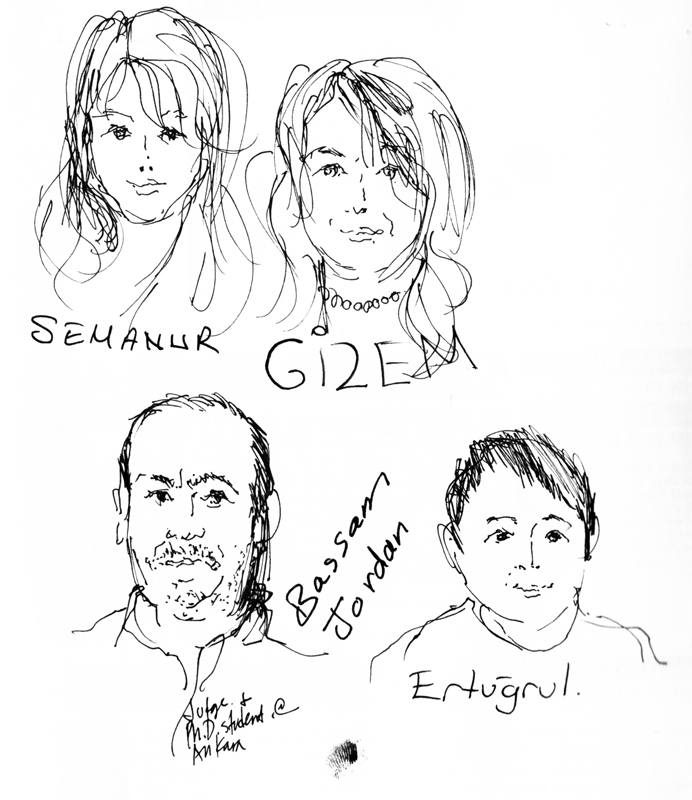

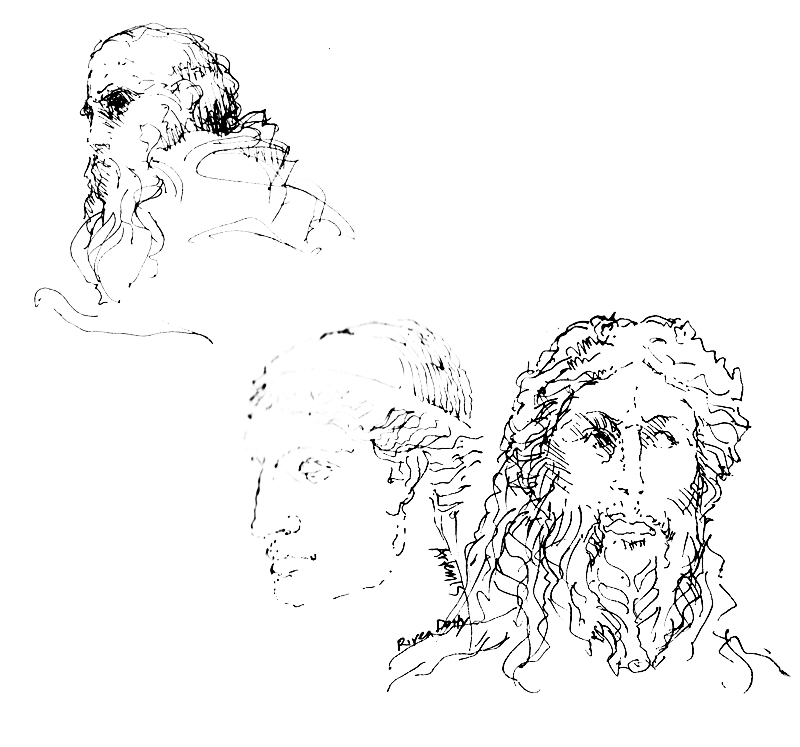

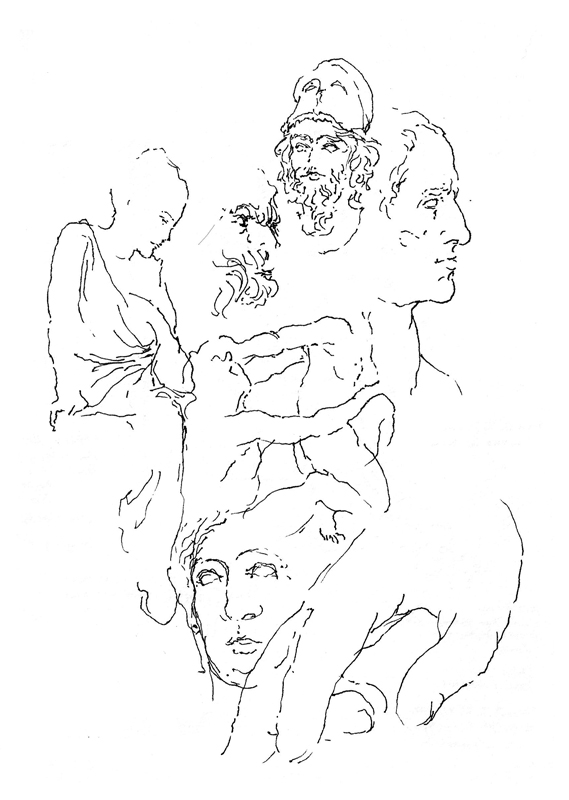

Faces

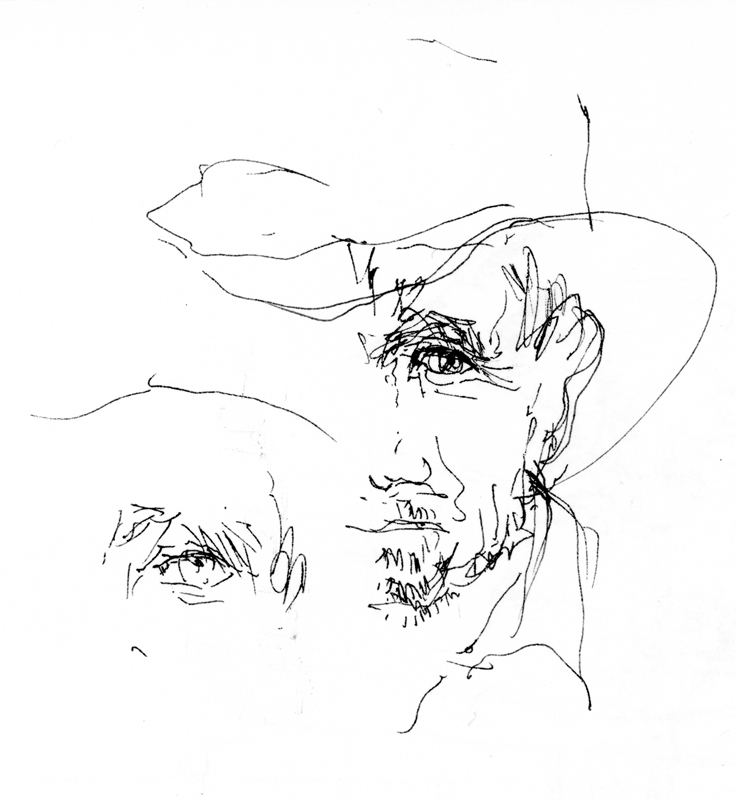

In the community of urban sketchers, architects are sometimes viewed as practiced in drawing buildings but not as adept at drawing people. While my focus is usually on capturing architecture and spatial environments, the drawing of people is often required to give scale to spaces and animate the places I try to capture in my work. And when drawing portraits, sometimes I am lucky enough to capture the personality of an individual with just a few well-placed strokes. At other times, I struggle and make people look younger or older than they really are.

The human face and body are difficult to draw, much more difficult than drawing architecture. Except for the cartoonists who are able to distort salient characteristics to emphasize the personality being caricatured, most of us can easily fall prey to mistakes in proportion and unintentionally distort our subjects. Still, drawing people is often necessary and always a challenge to draw. Good practice subjects are classical sculptures because they don’t move around as you try to draw them.

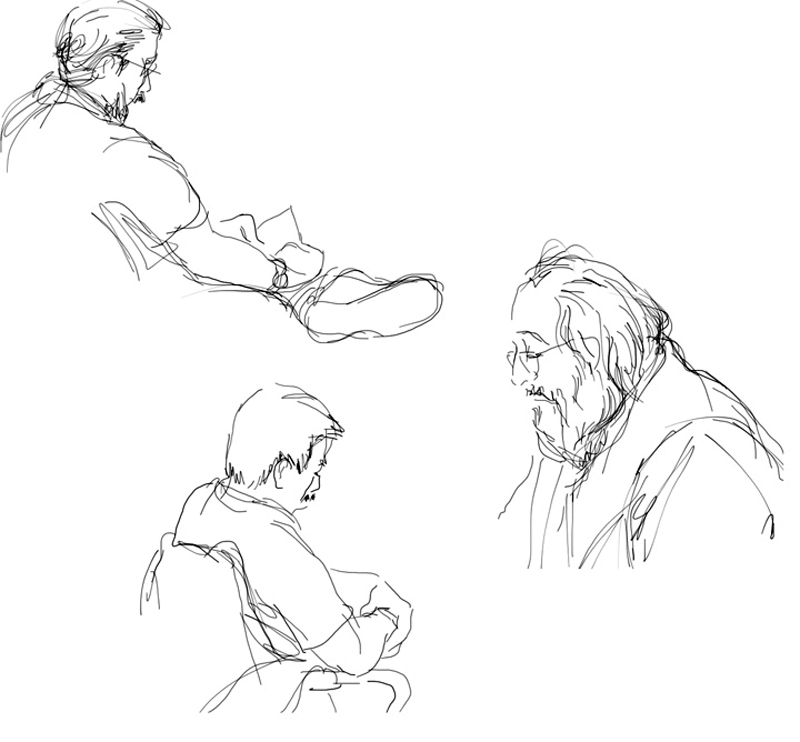

Gabi’s Book Signing

Last Sunday, I attended a book signing by Gabi Campanario at Elliott Bay Books in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle. In addition to The Art of Urban Sketching, the event featured two more of Gabi’s recent publications. The first is Seattle Sketcher, based on Gabi’s exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry highlighting his five years of work documenting the people, places, and events in the Pacific Northwest for the Seattle Times. The second is the first in a series of more focused urban sketching handbooks, Architecture and Cityscapes: Tips and Techniques for Drawing on Location. Both are highly recommended.

Fremont Brewing’s Urban Beer Garden

During the cool, gray days of Seattle’s fall season, we have to find interesting indoor places to draw. Yesterday afternoon, I chose Fremont Brewing’s Urban Beer Garden. The combination of an informal atmosphere and a large variety of artisanal brews makes this a great place to spend some time on a rainy day. And when the sun’s out, especially in the summertime, the space spills outward with long tables and communal seating. Fremont Brewing will soon be moving to a larger brewing facility closer to Ballard but will retain this space as a lab and experimental brewery.

This is a view of the converted industrial space that I drew while enjoying a pint of FB’s Cowiche Canyon Fresh Hop pale ale. I first sketched in a rough outline of the major forms and elements and then overlaid the people before filling in some of the details. I’m realizing more and more that my views are tending to be panoramic in nature just as my taste in camera lenses leans toward the wide angle rather than the telephoto.

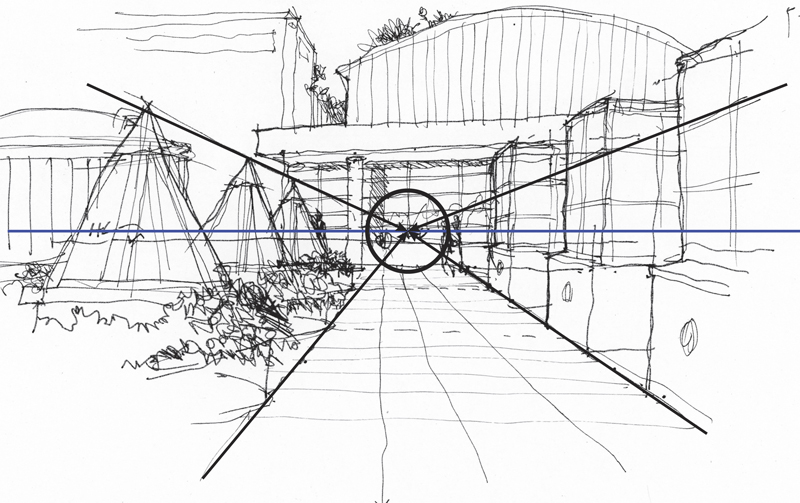

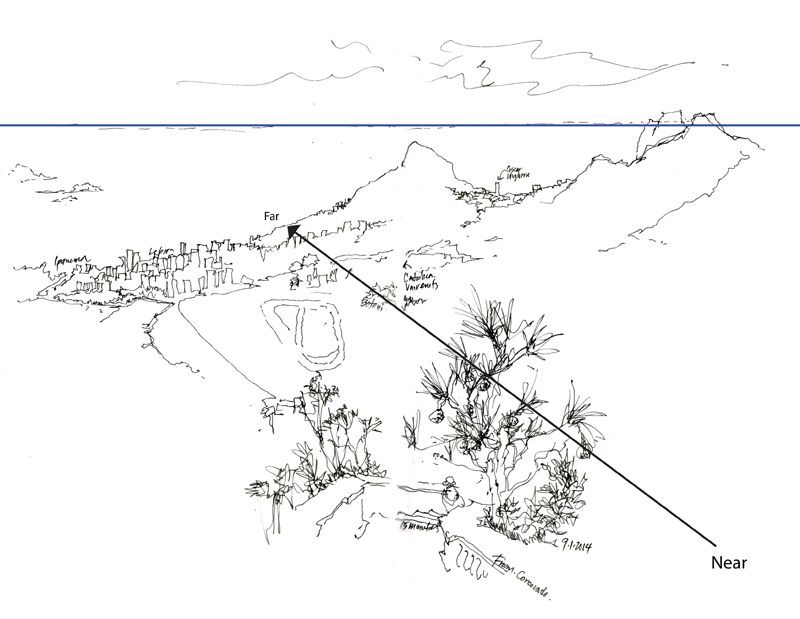

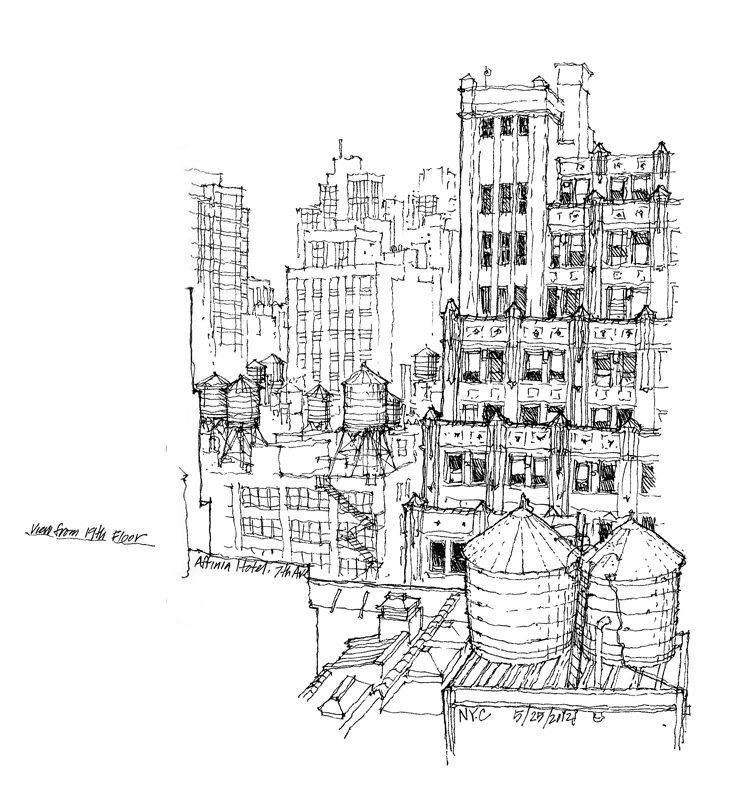

Surface and Depth

In the 1950s, the psychologist J.J. Gibson outlined a number of cues to depth perception. A few rely on our binocular vision and therefore do not apply to 2-dimensional drawings and paintings. Others, however, are psychological rather than physiological in nature. As such, these depth cues are pictorial in nature and are applicable to drawing and painting on a 2-dimensional surface. In the following, I try to use simple terms and snippets of my own drawings and photographs to illustrate each of the depth cues that I consider to be relevant to drawing on location.

Convergence of parallels: This is a key characteristic of linear perspective in which parallel lines appear to converge as they recede into the distance. Despite the usefulness of the other depth cues, linear perspective remains the structural scaffolding upon which to build a sense of spatial depth on the page.

Overlap: Near objects overlap or partially block the view of objects farther away. Locating effective overlaps can be useful in selecting a viewpoint and composing a drawing.

Position relative to the horizon: Objects below our eye level rise toward the horizon as they recede; objects above our eye level descend toward the horizon as they recede.

Relative size: Objects known or assumed to be of similar size appear to shrink in size with distance from the observer.

Texture gradient: Surface texture appears to get finer and smoother with distance from the observer.

Shading and shadows: Contrasts in light and dark can convey the shape, form and depth of objects.

Aerial perspective: Particles in the atmosphere affects the color and visual acuity of objects at varying distances from the observer; distant objects appear grayer or bluer and less distinct than nearer objects.

As we can see, scenes more often than not comprise a number of these depth cues operating simultaneously. Seeing how these depth cues occur in our real-life perception can aid our understanding of why things appear as they do, counter to what we know of the things we draw, which are often in conflict.