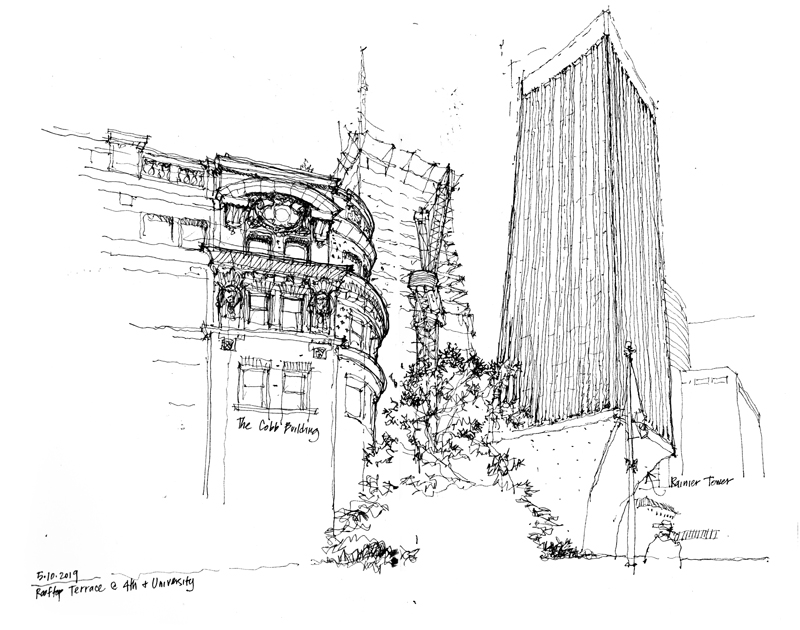

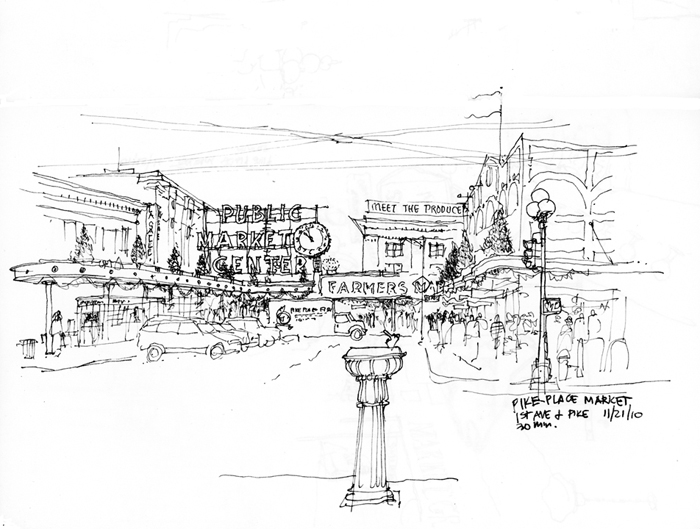

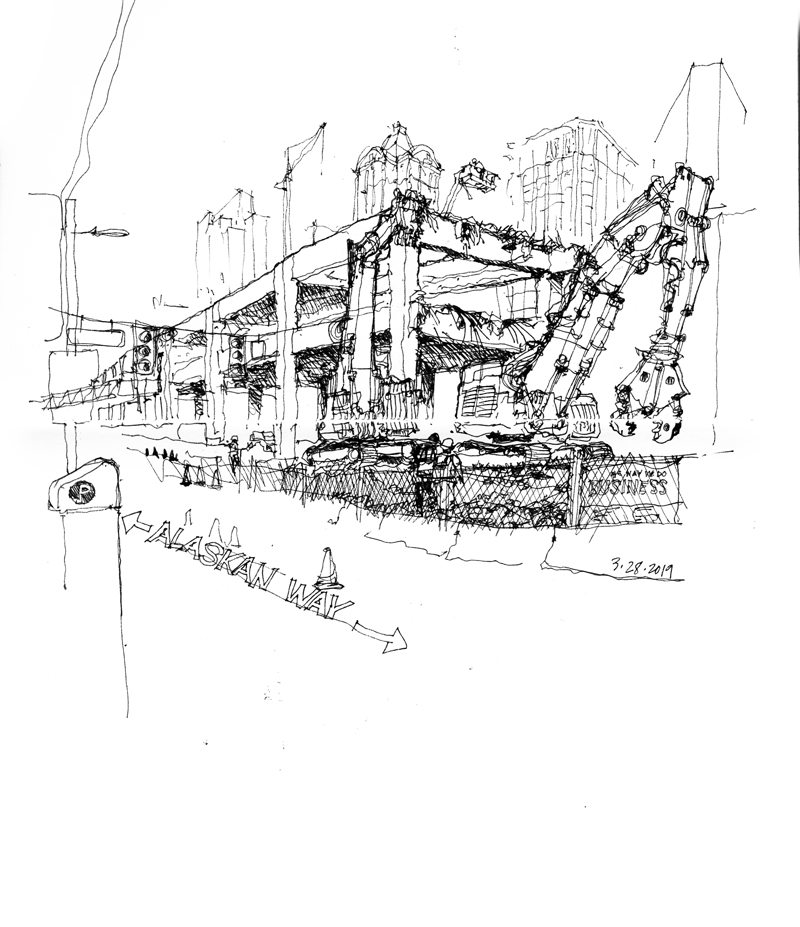

There are many ways to begin a drawing on location. For architectural subject matter, I typically search for a vertical plane that is both prominent and whose proportions are discernible to the eye. Placing this plane, correctly sized and in the proper location, will ensure that the entire intended scene will fit the page.

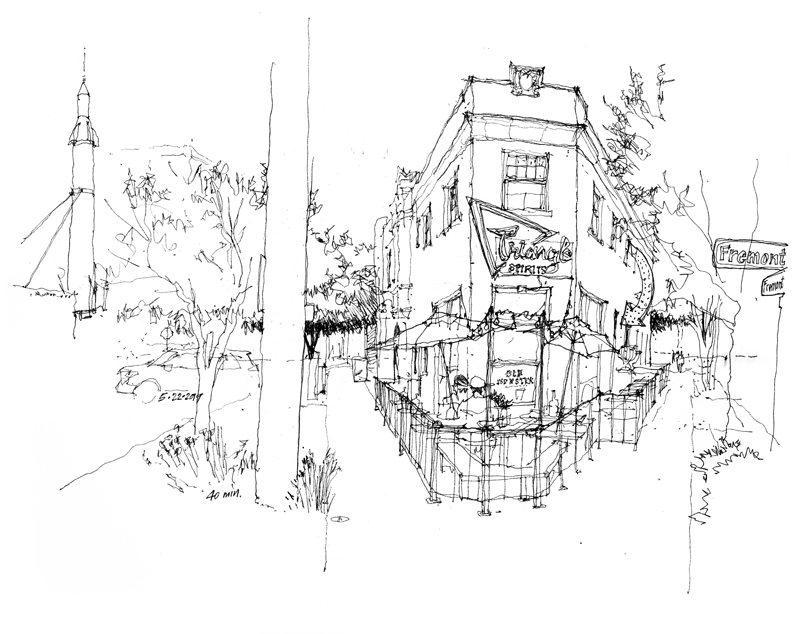

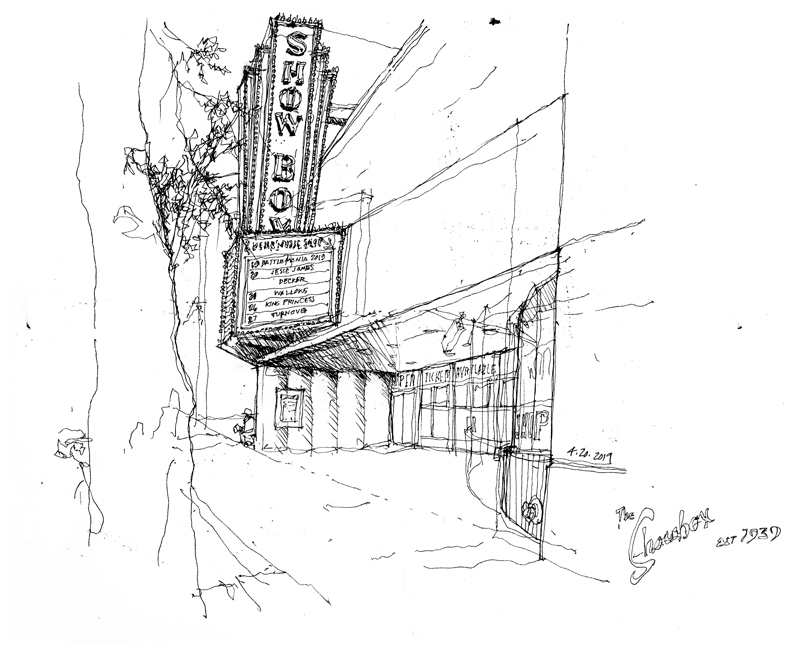

Anther place to begin is with an important vertical edge, which becomes in effect a measuring stick for the entire scene.

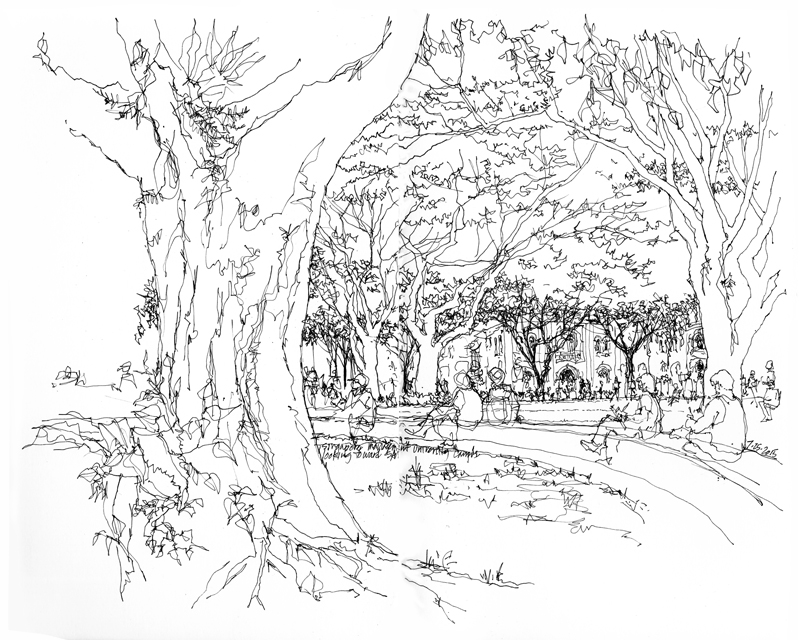

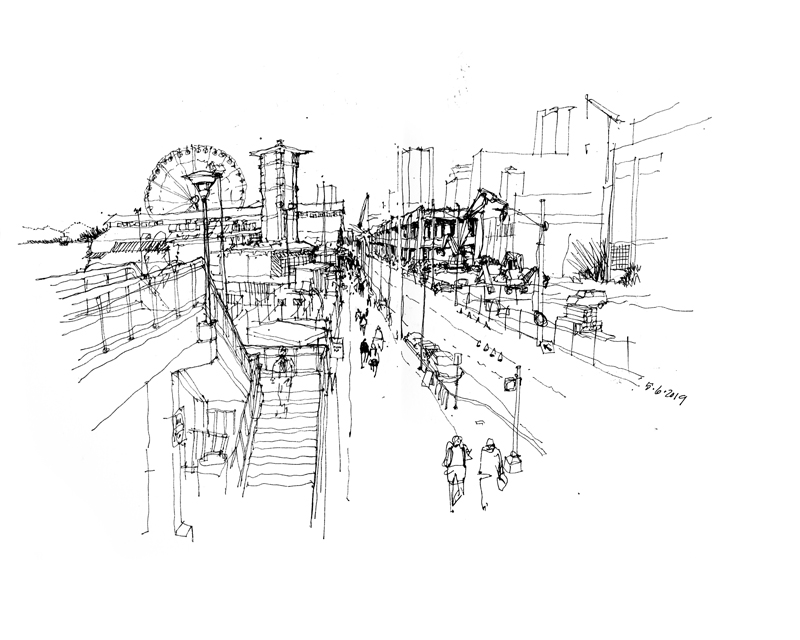

We can also begin with a vertical spatial plane, which is appropriate when drawing views of streets, alleyways, and the interiors of church naves and halls.

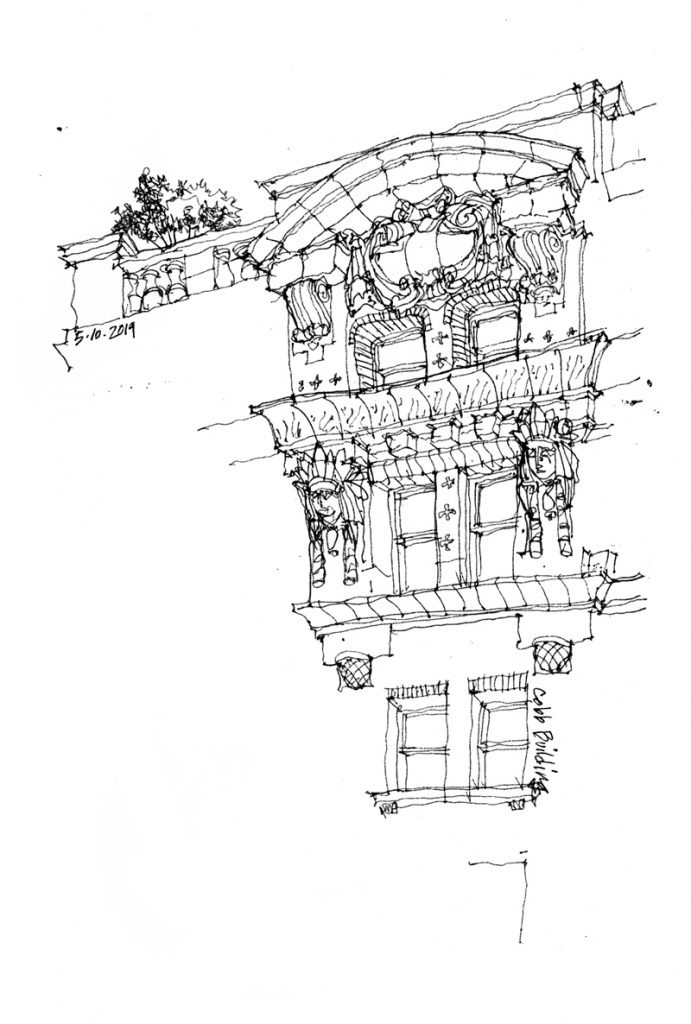

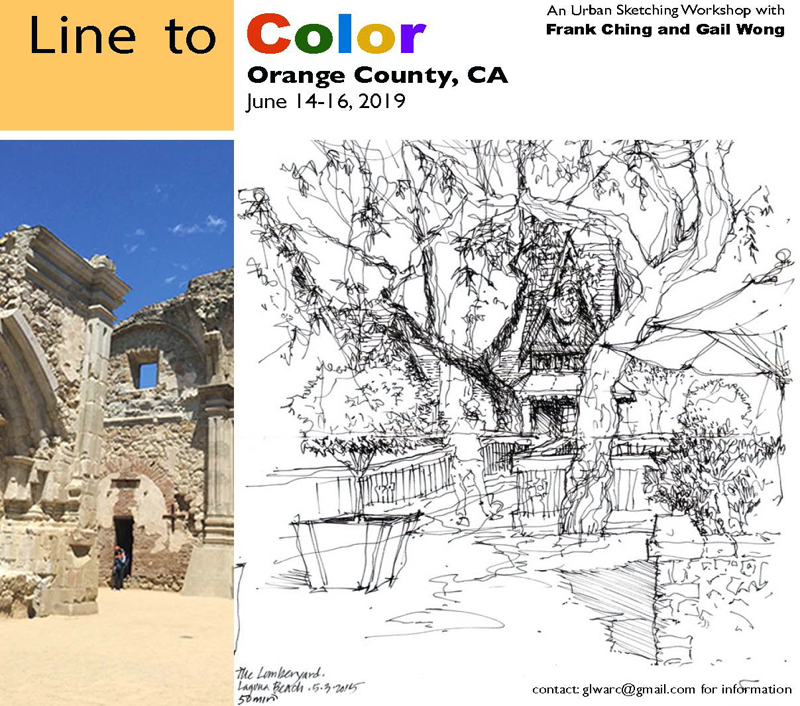

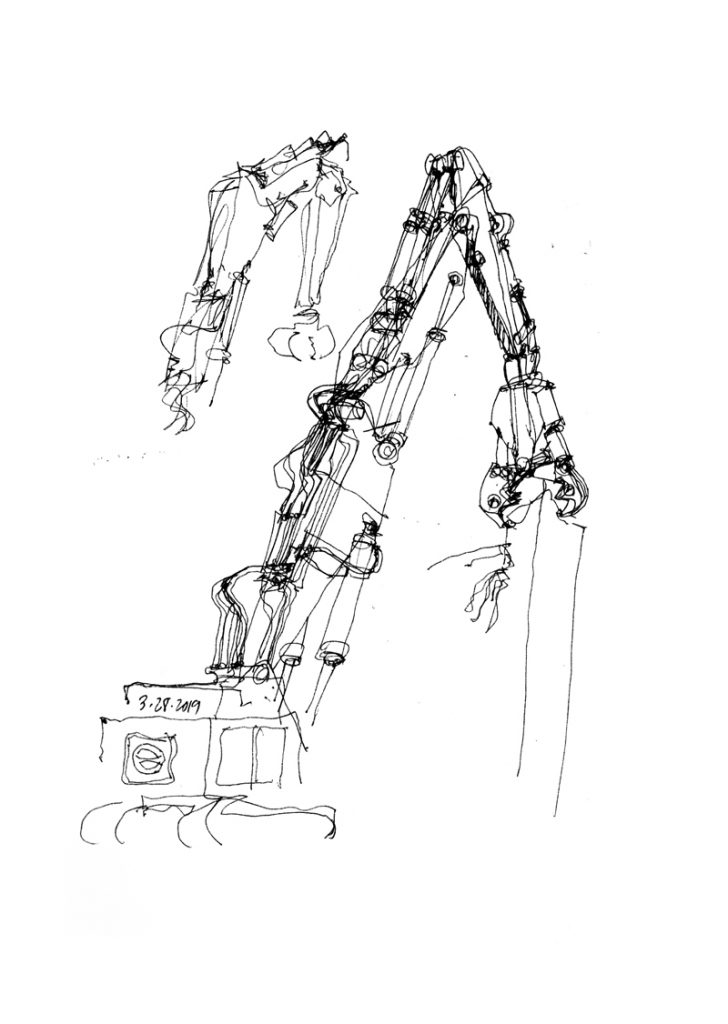

Or when there is no discernible geometry that can guide us, then we have to resort to capturing an unusual shape or opening.