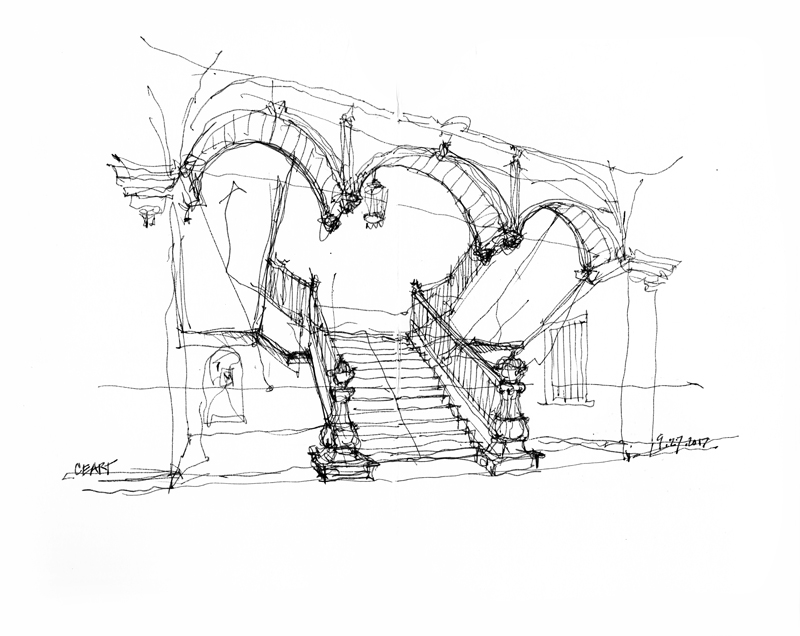

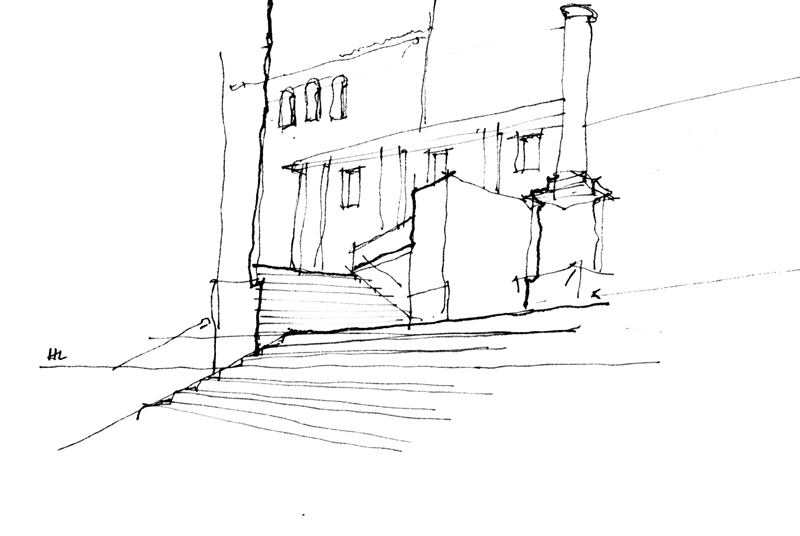

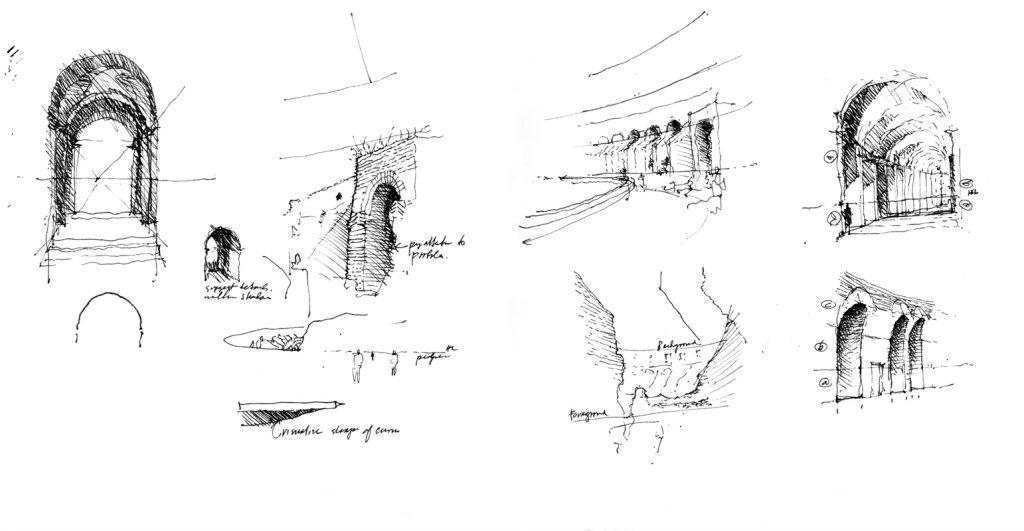

With opening day for the 2018 MLB season approaching, I thought it might be appropriate to post these sketches of Safeco Field, home of the Seattle Mariners. The stadium, designed by NBBJ and 360 Architecture along with the structural engineering firm of Magnusson Klemencic Associates, features a retractable roof that serves as an umbrella during inclement weather.

With opening day for the 2018 MLB season approaching, I thought it might be appropriate to post these sketches of Safeco Field, home of the Seattle Mariners. The stadium, designed by NBBJ and 360 Architecture along with the structural engineering firm of Magnusson Klemencic Associates, features a retractable roof that serves as an umbrella during inclement weather.

Although King County voters had initially turned down a proposal to fund a new baseball stadium to replace the aging Kingdome, the Mariners’ first appearance in the MLB postseason in 1995 and their victory in the American League Division Series reignited a public drive to keep the team in town. As a result, the Washington State Legislature approved an alternate means of funding comprising a mix of food and beverage taxes in King County restaurants and bars, car rental surcharges, a ballpark admissions tax, and sales of a special stadium license plate.

The stadium is often referred to as “The House that Griffey Built” because many believe major league baseball would not exist in Seattle without Ken Griffey, Jr.’s outstanding career with the Mariners. Griffey helped break ground for the new stadium in 1997 and a capacity crowd of 47,000 attended the Inaugural Game against the San Diego Padres on July 15, 1999.