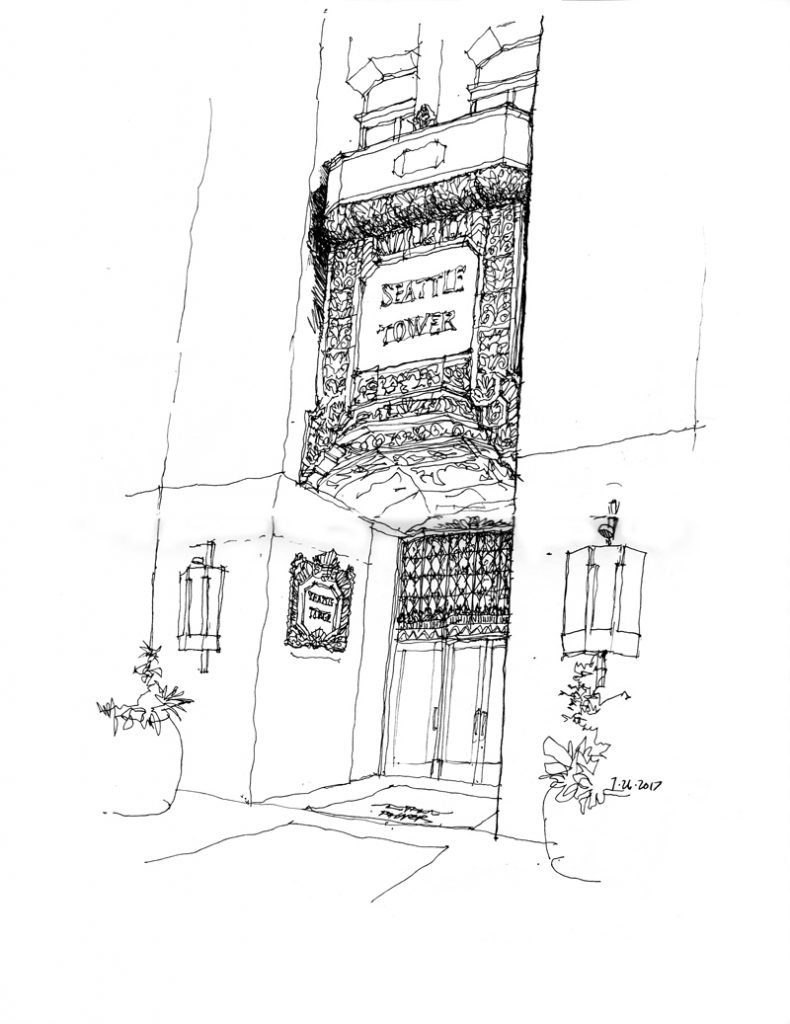

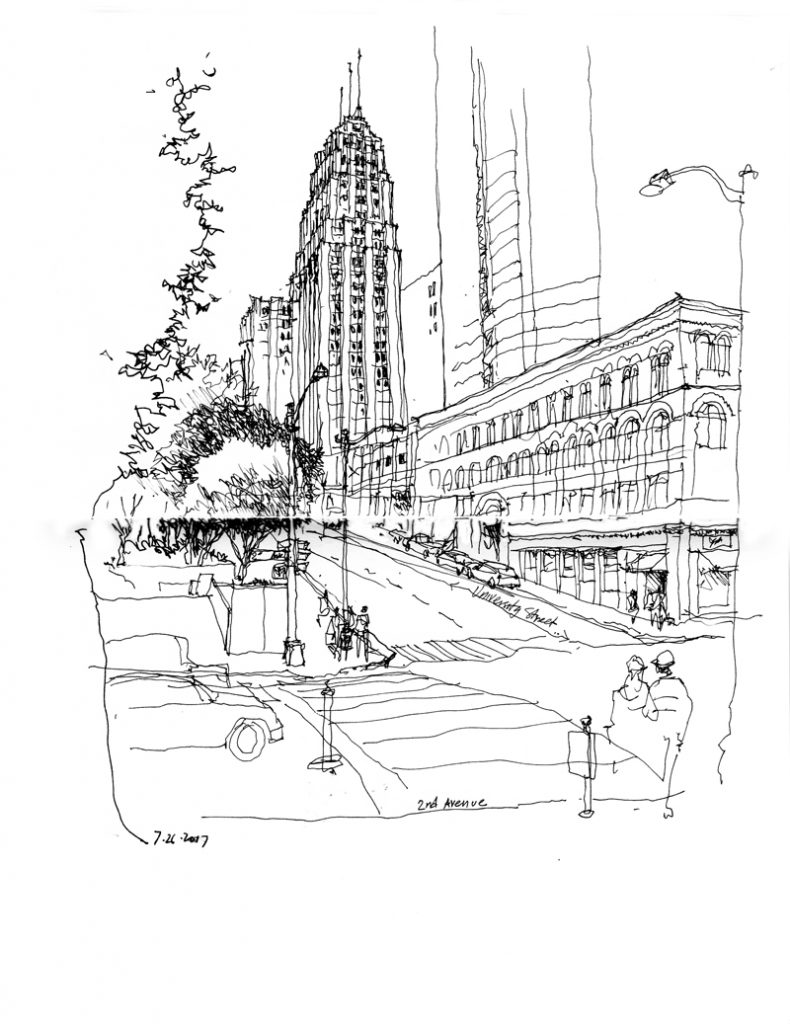

The Seattle Tower is a 27-story high-rise located at 1218 Third Avenue. Originally known as the Northern Life Tower when it was completed in 1929, the Art-Deco building was designed by Abraham H. Albertson in association with Joseph W. Wilson and Paul D. Richardson. Although not as tall as the Smith Tower, it rose one floor above “the tallest building west of the Mississippi” because it is situated at a higher elevation. A subtle design feature are the 33 shades of brick that progressively lighten as the structure rises from its base on Third Avenue.

The Seattle Tower is a 27-story high-rise located at 1218 Third Avenue. Originally known as the Northern Life Tower when it was completed in 1929, the Art-Deco building was designed by Abraham H. Albertson in association with Joseph W. Wilson and Paul D. Richardson. Although not as tall as the Smith Tower, it rose one floor above “the tallest building west of the Mississippi” because it is situated at a higher elevation. A subtle design feature are the 33 shades of brick that progressively lighten as the structure rises from its base on Third Avenue.

The Seattle Tower is now dwarfed by newer, taller skyscrapers but it retains its elegant and distinctive Art-Deco roots. It is City of Seattle Landmark number 137 and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.

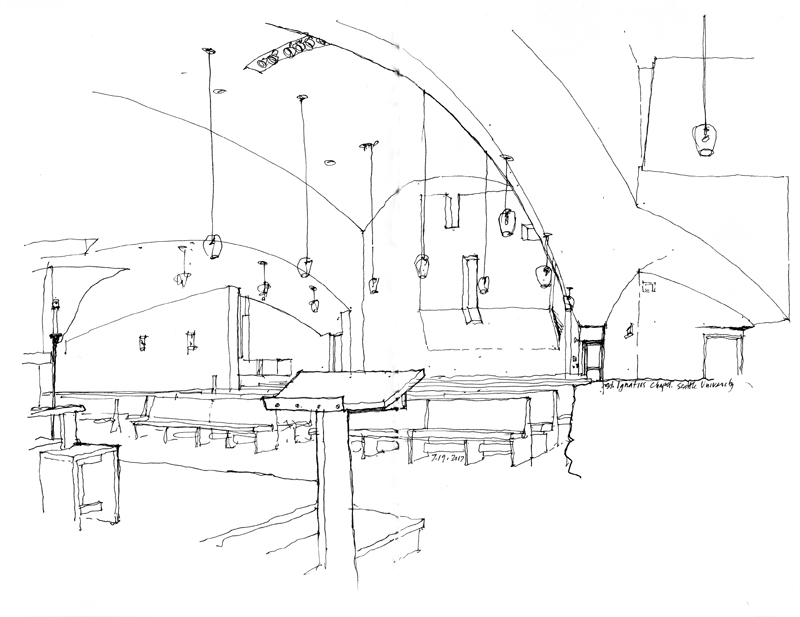

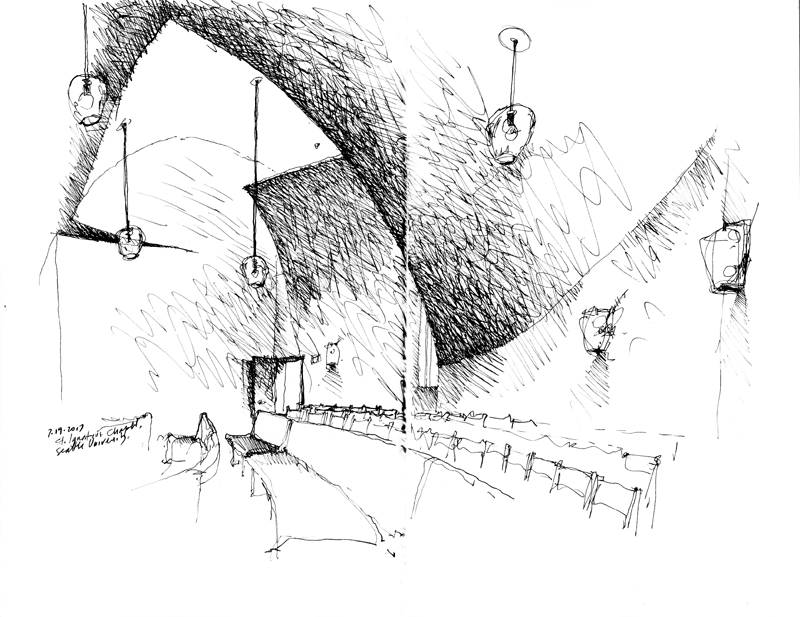

This last view if of the main elevator lobby, looking toward the entrance doors.