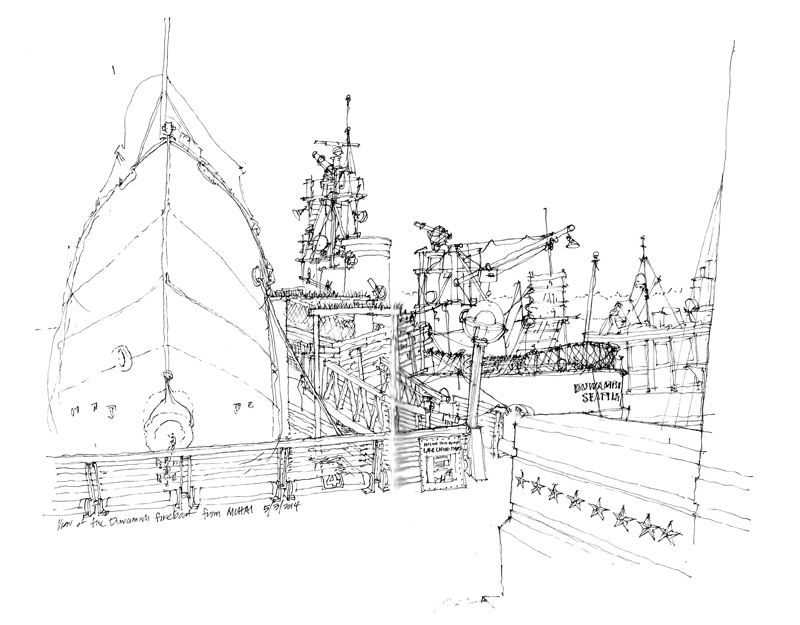

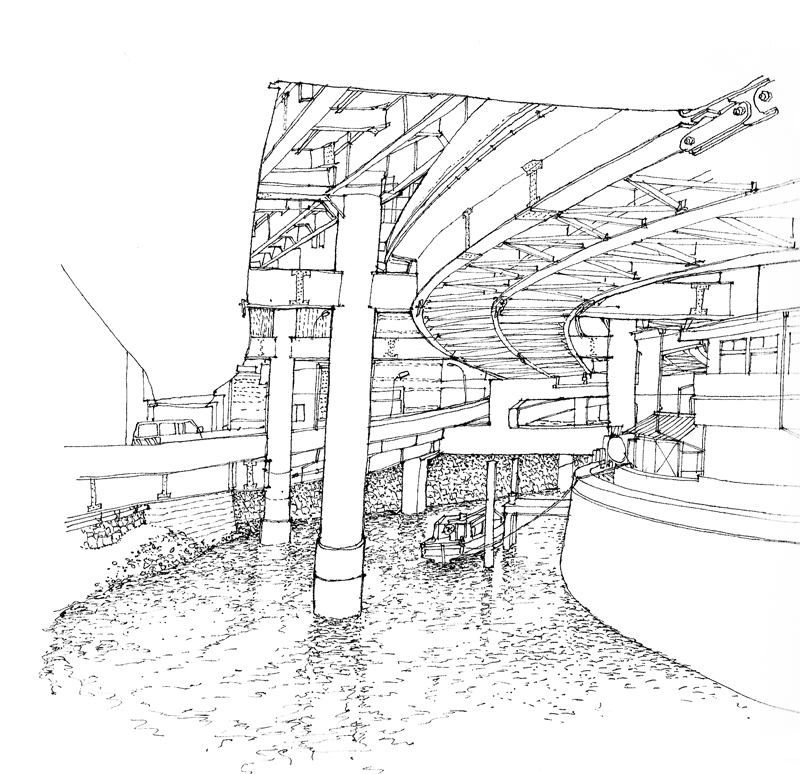

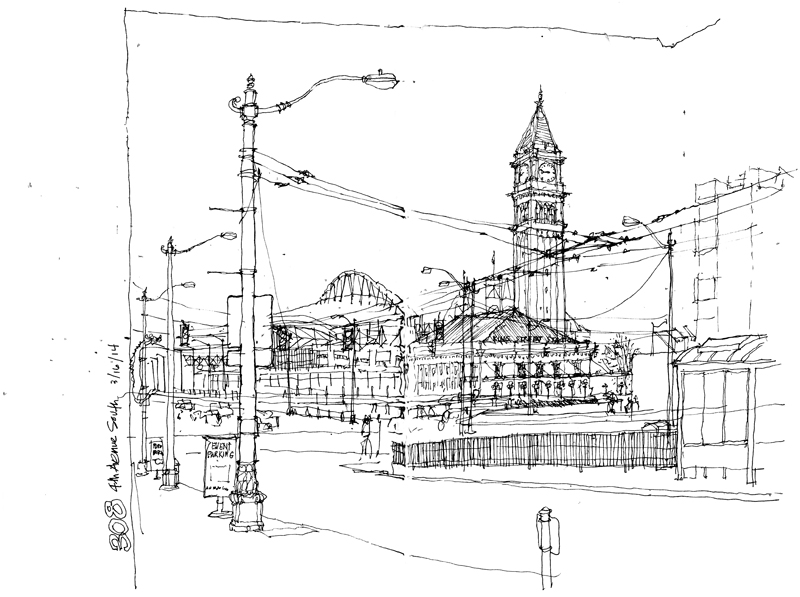

As part of Gabi Campanario’s Drawn to Seattle exhibit at the Museum of History and Industry, individual members of the Seattle Urban Sketchers have been spending Saturday afternoons as an “Urban Sketcher in Residence,” demonstrating and sharing their sketching techniques. Yesterday was my opportunity. After a few warm, sunny days, it turned cool and rainy again and so I had to draw from inside MOHAI. The first view is of the Duwamish, built in 1909 and the second oldest fireboat in the U.S., being retired in 1985 and now moored at the Historic Ships Wharf just north of the museum on Lake Union.

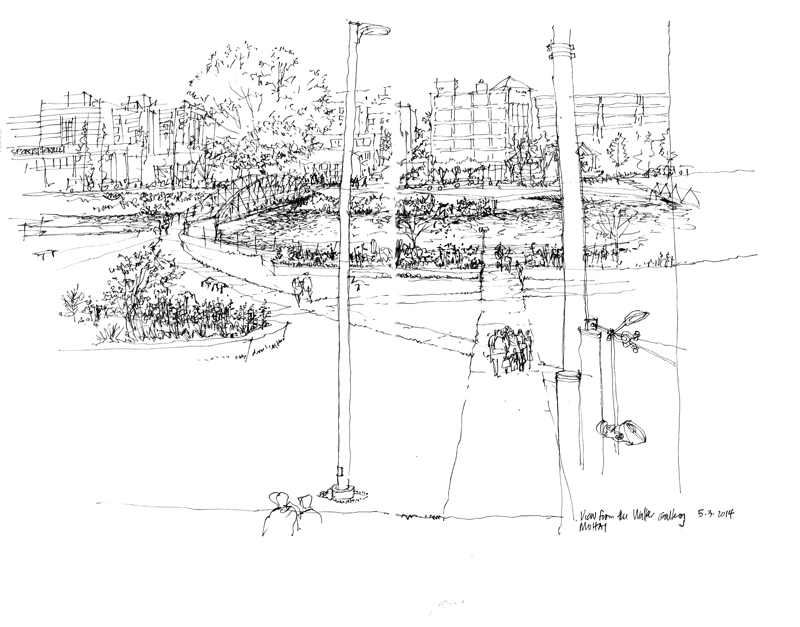

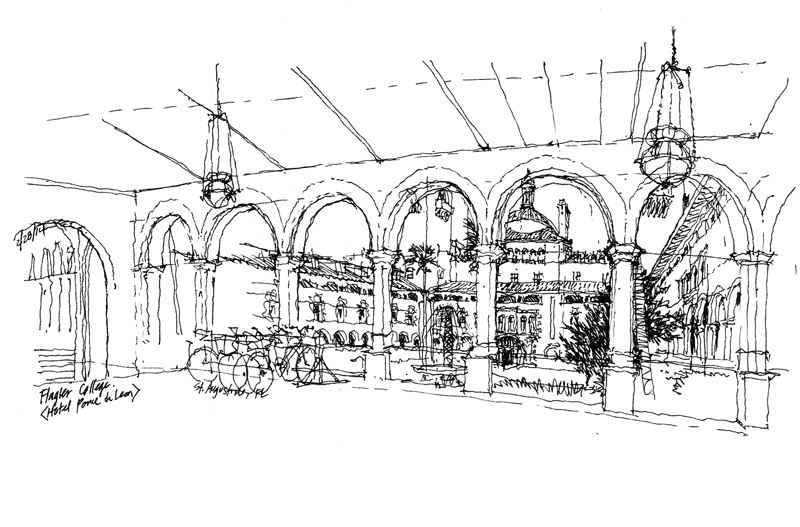

The second “drawing” consists of just three lines, but they represent for me the broad outline of the following sketch, drawn from the second floor Walker Gallery, where Gabi’s exhibit was located. With those three lines, I establish the overall composition of the view and the scale and position of the bridge, which is the focus of the drawing.