Architecture for Humanity is “…a nonprofit organization founded in 1999 to promote architectural and design solutions to global, social, and humanitarian crises. Through design/build projects, competitions, workshops, educational forums, partnerships with aid organizations and other activities, Architecture for Humanity creates opportunities for architects and designers from around the world to help communities in need. We believe that where resources and expertise are scarce, innovative, sustainable and collaborative design can make a difference.”

I quote this because the nonprofit is currently hosting a charity auction on eBay of drawings, paintings, and other artwork by a number of designers and architects, which ends on June 29. Check it out at:

http://cgi3.ebay.com/ws/eBayISAPI.dll?ViewUserPage&userid=architectureforhumanity

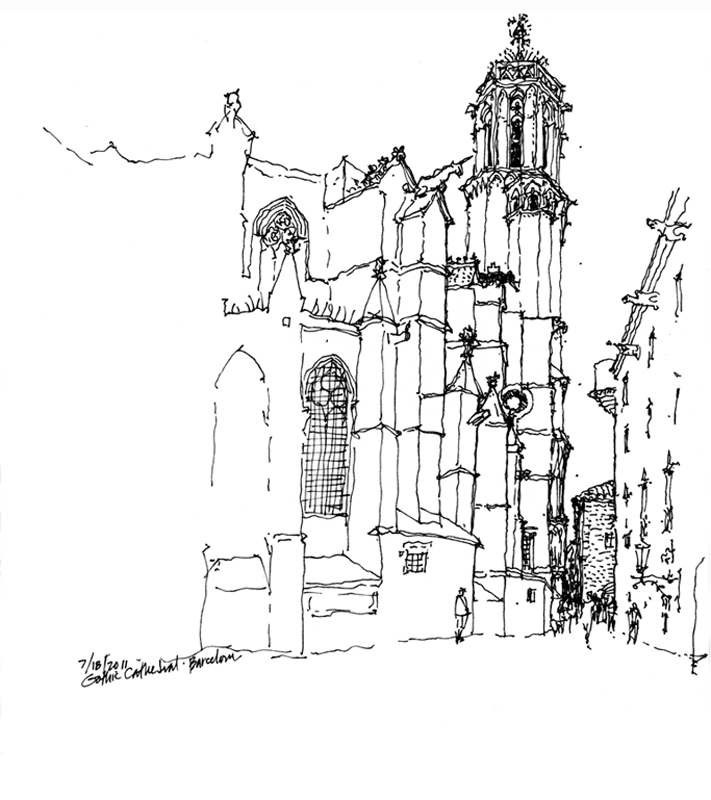

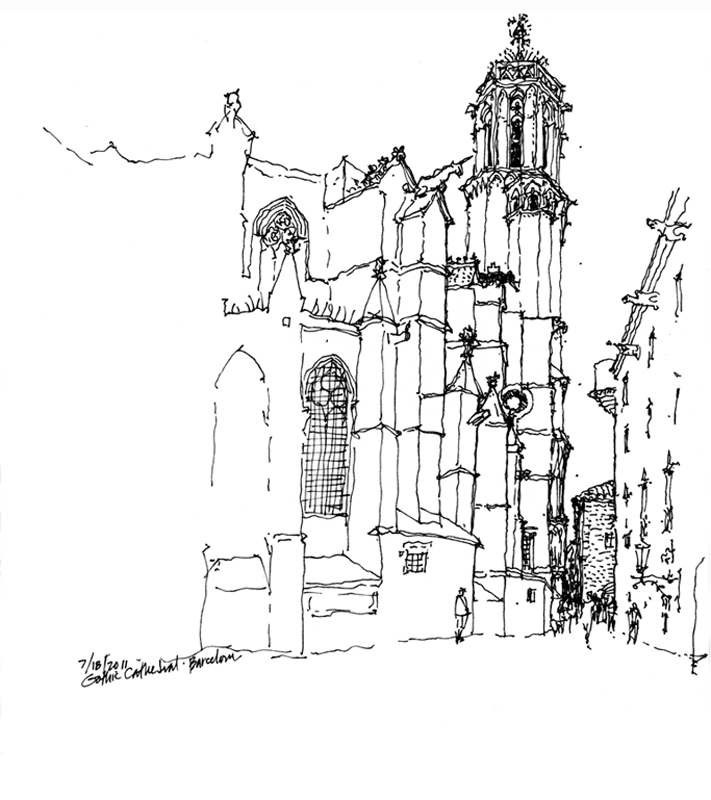

Here is a sketch of the Gothic Cathedral in Barcelona that I submitted for the charity event but It is not available for online bidding since it was actually raffled off at the AIA convention in May. Even if you’re not interested in purchasing anything, the auction site is worth perusing to see some interesting work by well-known designers, all donated for a good cause.